Jamaica

Basic Data

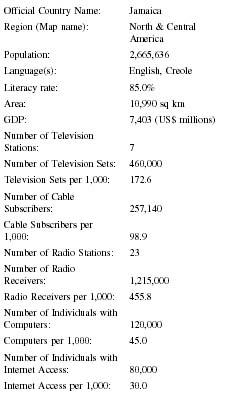

| Official Country Name: | Jamaica |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 2,665,636 |

| Language(s): | English, Creole |

| Literacy rate: | 85.0% |

| Area: | 10,990 sq km |

| GDP: | 7,403 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 7 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 460,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 172.6 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 257,140 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 98.9 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 23 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 1,215,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 455.8 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 120,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 45.0 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 80,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 30.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Jamaica supported a vast variety of media, ranging from daily newspapers to weekly shoppers, from news and editorial content to publications dedicated to spreading the word about the ample Jamaican culture. Jamaica had three daily newspapers: the Daily Gleaner , the Observer and the Star , an afternoon tabloid put out by the publishers of the Gleaner . The 's coverage of local news, sports and features was regularly of high quality, and the paper knew and was unafraid of expressing its voice. The Observer was founded in the early 1990s and was published in a tabloid format with a broadsheet bent. Both the Gleaner and Observer put out a Sunday paper. In addition to these local publications, some outside media made it to Jamaica; U.S. newsmagazines like Time and Newsweek were available at news stands, as were some of the major U.S. dailies (though they were frequently a couple of days out of date) and the Sunday broadsheets from the United Kingdom.

Of the papers supported by Jamaica, the Daily Gleaner seemed on the soundest footing in 2002. The Gleaner Company published the Daily Gleaner , the company's flagship paper. Established in 1834, it was the oldest operating newspaper in the Caribbean. The company added the Sunday Gleaner in 1939. It also published the Afternoon Star . There was also a Weekend Star that contained mostly reviews of Jamaican music, dance, theater, and social culture. It was first published in 1951. The Gleaner took no prisoners, particularly in its political coverage. It earned its reputation in its coverage of the Manley administration of the 1970s, and in the early 2000s it took on all parties with its non-partisan coverage. In an effort to promote education, the Gleaner Company also began publishing The Children's Own , a weekly put out during school terms to promote creative learning. In 2002, the Gleaner Company had perhaps the strongest presence in Jamaica. The group had offices in Toronto, Ontario, Canada; London; and New York in addition to its headquarters in Kingston. The newspaper group made nearly $1.8 million in 2000, after making just over $1.6 million in 1999.

The Gleaner targeted young, male readers. It drew 54 percent of its readers from males. Some 56 percent of its readers were between the ages of 18 and 34, with another 26 percent between 35 and 44. Only 18 percent of the Gleaner's readers were 45 or older. Of the chain's readers, 43 percent made between US$31,000 and US$45,000 a year; some 32 percent make US$30,000 or less. Only 12 percent earn US$46,000 or more.

Many of Jamaica's other, less traditional publications focused on the country's culture, music and entertainment. For instance, Destination Jamaica was an annual publication that focused primarily on the hospitality industries. Track and Pools , another Gleaner publication, covered the racing industry. Moreover, the Weekend Star complemented its daily publication with more information about local music, dance, theater and the social culture.

The Star , another Gleaner publication and the island's tabloid, provided the more salacious stories not found in the more-traditional newspapers. A similar publication, X News , provided entertainment listings and news from the music world.

Other regional publications helped keep readers in their areas informed. The Western Mirror was published in Montego Bay for the western side of the island, while the North Coast Times , based in Ocho Rios, was a tourist-oriented publication. The Observer , founded by Gordon "Butch" Stewart in the early 1990s, rivaled the kind of coverage found in he Gleaner . However, most observers appeared to feel the paper sometimes struggled to figure out its target audience.

While Jamaica supported several quality print publications, radio was also popular in the country. Its roots could be traced to a ham radio operator, John Grinan, who in 1939 while operating at the start of World War II, followed wartime regulations and turned his equipment over to the government. Thus, Radio Jamaica was born. Grinan convinced government officials to use his amateur equipment to operate a public broadcasting system, and the government adapted his equipment to match demands. Regular scheduled broadcasts started from Grinan's equipment, the first one coming November 17, 1939. Indeed, the first radio station, VP5PZ, took its name from Grinan's call-sign. At first there was only a single broadcast per week, emanating from Grinan's home. After May 1, 1940, though, the station picked up a small staff. Daily broadcasts started in June 1940.

The broadcasts got better and better, despite the adversity of working in an inadequate facility. The first program manager was appointed and the station started offering more and more options, in addition to news and wartime information. Eventually, broadcasts included live performances of local artists. As of 2002, most of Jamaica's radio was dedicated to this kind of perpetuation of local artists and culture. But back then, running the station became financially prohibitive for the government, and the decision was made to issue a license to a private company to provide the broadcasting services.

The Jamaica Broadcasting Company, a subsidiary of the Re-diffusion Group in London, England, got the first license in 1949. The license allowed Jamaica Broadcasting Company to operate regular broadcasting, and the company took over the operations of the station, known as ZQI since 1940, on May 1, 1950. Commercial broadcasting began on July 9, 1950. Thus was born Radio Jamaica.

The new company was handed the responsibility of covering the entire island with radio broadcasting. Not wanting to limit it to urbanites, the mandate was to have rural residents exposed as well. To make sure that happened, the company distributed wireless sets to about 200 listening posts around the island. They were placed at natural gathering spots, like schools, police stations, and stores around the various villages.

One important mandate was that the radio broadcasting would be commercial, meaning they would have to figure out how much air time was worth, and advertisers for the first time would be forced to pay for the time used for their advertisements. It was decreed the station's only revenue would come from these advertisements and from sponsorships of individual broadcasts. Consequently, listeners for the first time had their programming interrupted with commercials.

In August 1951, the station moved, from its original location to what, at the time, was called a "modern, air-conditioned and excellently equipped" studio. Two years later, the station made history, installing frequency-modulated transmitters. Radio Jamaica thus became the first country in the British Commonwealth to broadcast regularly scheduled programming on the FM band.

In February 1951, the station decided it needed to expand the radio's reach. The company started a re-diffusion service, using a division of Jamaica Broadcasting Company Limited, to provide programming transmitted by wire. Carried to homes, retail outlets, bars, hotels, and the like, the service became quite popular, particularly because it offered something that had not been available: total coverage of national events. By 1958, more than 15,000 subscribers had this service.

Non-stop music became a staple of Radio Jamaica in the early 1960s, when Reditune , a tape machine system that provided non-stop, but taped, music of various sorts. The tape system eventually gave way to the more sophisticated Musipage system, which broadcast the music live from the station. In 1972, Radio Jamaica introduced a second daily radio feed on the FM band. RJR-FM filled a need for soothing, uninterrupted music. Radio Jamaica purchased the television and Radio 2 assets from the Jamaican Broadcasting Corporation, the government-owned system, for about $70 million Jamaican. With all its success, Radio Jamaica Limited evolved. In 2002 it was doing business as the RJR Communications Group, the largest electronic media corporation in the Caribbean. The RJR umbrella sheltered Radio Jamaica Limited, Television Jamaica Limited, and Multi-Media Jamaica Ltd. The goal, apparently realized, was to touch the lives of the majority of Jamaicans through coverage of news and world affairs and the entertainment industry, with some educational and informative programming as well.

Economic Framework

In the early 2000s, agriculture employed more than 20 percent of Jamaica's population. Bauxite, aluminum, sugar, bananas, rum and coffee were key exports from the island, with tourism responsible for an important part of the island's economy. The government's austerity program lowered inflation nearly 20 percent in six years, from 25 percent in 1995 to around 6 percent in 2000 (al-though it was up to about 7 percent in 2001). A declining gross domestic product, according to some sources, showed signs of recovery. The per-capita GDP was roughly $3,389. The GDP grew by 0.8 percent in 2000.

More and more Jamaicans began to earn a decent living, although the island's unemployment rate in 2000 was around 15 percent nationally and even higher among women. More than a quarter of the island's population lived below the poverty line, and 13 percent lacked health care, education, and economic opportunities. The central bank prevented a drastic decrease in the exchange rate, although the Jamaican dollar has still been dropping. At the end of 2001, the average exchange rate was $47 Jamaican dollars to US$1.

According to information compiled by the U.S. Department of State, weakness in the financial sector, speculation, and low levels of investment erode confidence in the productive sector. The Jamaican government raised US$3.6 billion in new sovereign debt in 2001, which was used to help meet its U.S. dollar debt obligations. Net internal revenues, according to the Department of State, rose from US$969.5 million in the beginning of 2001 to more than US$1.8 billion by the end of the year.

In terms of the newspaper industry, Jamaica's import figure for paper and paperboard stood at just under US$90 million in 1996, whereas it had grown around 20 percent every year between 1992 and 1995. After that, though, the growth stalled due in large part to a recession. However, some areas continued to do well, including newsprint, sanitary napkins, and various types of tissue. The Jamaican government continued a gradual reduction in overall duties, to the point that some import categories had no duty, including paper used in the printing industry, corrugated paper and paperboard, cigarette paper, and dress patterns.

The combination of high interest rates and an increase in the availability of better-quality imported products put some small amount of pressure on local manufacturers. The United States had 60 percent market coverage and was the country's major source for paper and paperboard products. Other countries, among them Canada (newsprint) and Trinidad (sanitary paper items), were also quite competitive.

In 1992, Jamaica imported US$2.3 million in news-print rolls; by 1996, it had grown to US$7.5 million. Newsprint formed one of the significant import segments for Jamaica. Several newspapers were now printed nationwide: the Gleaner , the Observer , and the Herald . In 1996, importation of newsprint accounted for 8.6 percent of the total paper products imported. The import market share, therefore, had more than doubled in four years. In fact, 1995 showed more import than 1996, but that was almost certainly because the Herald quit publishing daily in 1996.

Relatively high interest rates for most commercial enterprises, in addition to the higher quality of imported goods, had a negative effect on the production inside Jamaica in the 1990s. These facts were proven by the import figures for things like paper for printing, toilet tissue, and sanitary towels.

The local printing industry complemented the manufacturing industry, so any stagnation or lack of growth in general manufacturing would be reflected through lack of growth in the total market for printing products (including paper); therefore, a gradual decrease in these imports would be seen.

The United States continued to be the major import source of paper products and paperboard. In 1996, the overall market share for the U.S. was 60 percent. The United States dominated some areas, such as Kraft paper-board, where their market share is 97 percent, and writing and printing paper (80 percent). There was considerable competition in other categories; for instance, Canada was the source for about 80 percent of newsprint.

According to the U.S. Department of Commerce National Trade Data Bank (November 2000), paper and paperboard were very broad groupings which covered three main uses: communication, packaging, and hygiene/sanitary use. Despite growth in the use of computers, e-mail, and other electronic means of corresponding, paper continued to be an important medium for allowing communication. Major-end users are newspapers (newsprint), the printing industry, government agencies, and private offices involved in commercial activities.

Of Jamaican newspapers, the Gleaner claimed the highest circulation, boasting 100,000 copies printed on Sundays. Since late 1997, the Gleaner company had a deal to publish a daily international edition of the Miami Herald. Moreover, the printing industry in Jamaica in the early 2000s consisted of several companies which worked in tandem with various commercial enterprises and government agencies in the production of various items such as labels, letterheads, business cards, flyers, newsletters, brochures, magazines, annual reports, calendars, posters, computer forms and greeting cards, etc.

The government of Jamaica and its various ministries and agencies are big users of paper for communication, administration, and recording purposes. Significant government organizations which spring to mind in this area include the Jamaica Information Service, the Inland Revenue Department, the Electoral Office, the Statistical Institute of Jamaica and the Ministries of Finance and Health.

Press Laws

The Jamaican Senate in June 2002 passed the country's first Access to Information Bill, the equivalent to the U.S. Freedom of Information Act. The bill did cause consternation, however, because of a clause that allowed the minister of information to exclude any statutory body from the influence of the information law. Minority senators objected on grounds that the clause gave the minister sweeping powers to exclude entire agencies from the purview of the information law, rather than exempting specific documents. The clause did provide for an approval authority; however, the minister had to obtain "affirmative resolution" or the consent of both houses of parliament. Nine government senators voted in favor of the clause, while three Opposition and two independent senators objected. At the same time, the Cabinet reviewed detailed proposals for a law to replace the Official Secrets Act, an antiquated law that generally provided for penalties to public officials for disclosing information.

In 2001, the government agreed to amend a new law that made it a crime to report on certain government investigations. The so-called Corruption (Prevention) Act was designed to bring Jamaica into compliance with the 1996 Inter-American Convention against Corruption. Under the bill, journalists could be fined up to US$12,250 or jailed for up to three years, or both, for publishing information about the work of any state anti-corruption commission. After several media and civic groups conducted seminars and published information about the offending clauses, the government passed the bill without them.

Censorship

In the early 2000s, some aspects of the media were under government control. The biggest issues facing the press concerned the limits to its freedom, the responsible use of that freedom, the relationship between the press and the Jamaican government, the influence of imported content, and the role of the press in the development of young, independent countries.

State-Press Relations

Despite some government control over the media, generally speaking the press acts independently. According to Jamaican columnist Martin Henry, the English-speaking commonwealth Caribbean has largely a free press. Still some issues connected to state-press relations were raised at a 2001 conference in Jamaica, which co-occurred with violent protests in the country. The minister of finance had announced a large tax hike on gasoline. After a quiet weekend, some protests began the following Monday, intensified, Henry believed, at least in part by the media.

At noon the first day, a few scattered roadblocks, which are a popular form of protest on the island, were set up. The situation was reported on midday broadcasts. By later that afternoon, Kingston was practically shut down by roadblocks, violence had escalated, and nine people had been killed.

The problem, as many observers saw it, was that the media were allowed to report on the protests, but they were not allowed to report on the inner workings of the government because of the Official Secrets Act. The act, journalists believed, restricted such access, and thus impeded the flow of information to the public. Had the public had more information about why the government felt the need for the tax hike, perhaps the violence could have been avoided. When the government did release more detailed information, protesters withdrew.

Protesters wanted media coverage. According to Henry, roadblocks became a popular form of protest because they often provided a chance for dramatic footage. Protesters frequently refused to disperse until after the cameras arrive. Then, too, the media themselves questioned the government. The Daily Gleaner and the Observer both frequently and with justification question the politics, practices, policies, and procedures of government and political parties.

One visible forum for political discussion is the talk show, which flourishes in Jamaica and across the Caribbean, for that matter. Some of the talk shows ardently pursued government accountability, pressing particularly about libel laws and the Official Secrets Act. Before the tax protests, the more critical talk show hosts were accused of being negative. After the protests, in which nine people died, they were perceived as more justified.

Many problems were ready topics. High unemployment, underemployment, growing debt, and high interest rates were among the most serious of Jamaica's economic problems. Both major political parties had ties with two large trade unions.

By the end of the 1960s, it was evident that media was going to play a key role in the establishment of nationhood. According to information obtained on the Web site of the Caribbean Institute of Mass Communication (CARIMAC), the problem was that most of the people working in the media were "outsiders" lacking in any kind of Caribbean perspective. So, in 1969, the Jamaican government started looking into the idea of putting a regional media-training center on the island, in an effort to correct the problem. Finally CARIMAC was located at the University of the West Indies (UWI) at Mona, and it followed certain principles. The program had a theoretical basis and a foundation in the Caribbean environment; it included courses in social sciences and communications, as well as in Caribbean studies. In addition, it gave practical training in mass media, concentrating on writing, interviewing, and production. The program was also designed to address the needs of media at all levels. With help from a variety of international and national agencies, the one-year degree program in mass communications was established at UWI-Mona in October 1974, with 31 students in the course.

CARIMAC moved four years later. In 1977, three years after the establishment of CARIMAC, a bachelor's degree program was added. Students of the Faculty of Arts and General Studies were able to choose from three different degree programs: Social Sciences with Communications; Languages and Literature with Communications; and Social Sciences, Languages, and Literature with Communications.

The institute continued to evolve. In 1990, the semester system was adopted, and students could choose from a wider curriculum. In 1994 CARIMAC added a master's degree program (in Communications Studies). The program consisted of a combination of formal lectures and seminars, taught by an inter-disciplinary team of instructors. In 1996, CARIMAC changed its name to The Caribbean Institute of Media and Communication. Then, in 1998, the undergraduate degree was revamped. First, the school added two new specialties, multimedia and public relations. Then, improvements were made to existing areas: Print became Text and Graphic Production; and audio-visual became Social Marketing. Television and radio were switched to Broadcasting Skills (Television) and Broadcasting Skills (Radio). Finally, new communications electives were added to reflect industry changes and technological advances. In addition, CARIMAC had an active outreach program, hosted regional seminars in various countries, ran workshops and conferences, and offered in-serves training for members of the media.

As part of the UWI, CARIMAC helped both governmental and non-governmental development agencies in the Caribbean. The institute assisted in communication methods and technology for development purposes in health, agriculture, community development, public education, and other areas. Moreover, as the only regionally recognized tertiary-level training program to media and communication in the Caribbean, CARIMAC was also the Caribbean's representative in the network of Global Journalism Training Institutions (Journet). CARIMAC trained students for work in print, radio, video, multimedia, and public relations.

Another group of great interest in the Caribbean, the Caribbean Environmental Reporters' Network (CERN), developed out of a training workshop in Jamaica in July 1990. In November 1992, at a follow-up workshop in Barbados put on by CARIMAC and the Caribbean Conservation Association, the concept was formally approved, and CERN was born. From the 10 journalists who originally formed the network, the staff grew to more than 35 journalists in 13 Caribbean states. CERN collaborated with media houses across the region, providing these organizations with accurate, up-to-date coverage from a Caribbean perspective.

CERN hoped to host one regional gathering every year on a topic pertaining to environmental journalism so that reporters would learn more about these issues. Too, CERN offered networking and information exchange possibilities between reporters throughout the Caribbean who had similar interests. These professional connections supported the dispatch of reporters to international events around the world, thus achieving broader media coverage of environmental issues.

CERN produced a weekly radio magazine series on community environmental action in the Caribbean, entitled Island Beat. The 10-minute program aired on more than 25 stations in 15 countries every week. It was distributed through the CANA Satellite network.

News Agencies

The government is served by the Jamaica Information Service (JIS), which, through radio and television programs, video recordings, advertisements, publications, and news releases disseminates information on government policies, programs, and activities.

Bibliography

Committee for the Protection of Journalism. Attacks on the Press, 2001. Available from http://www.cpj.org .

Henry, Martin. Tax Protests Focus Jamaican Media's Role. The International Communications Forum, 2001.

Jamaica Gleaner Internet Edition, Feb. 7, 2002. Available from http://www.jamaica-gleaner.com .

Jamaican History, 2002. Available from http://radiojamaica.com .

"Information Bill Gets Rough Passage in Senate." Jamaica Observer Internet Edition, June 29, 2002. Available from http://www.jamaicaobserver.com .

"Media," Jamaica Information Service, 2002. Available from http://jis.gov.jm/information/media.htm .

Thomas, Polly, and Adam Vaitilingam. "Rough Guide to Jamaica," 2001.

U.S. Department of Commerce. National Trade Data Bank, November 3, 2000.

Brad Kadrich

yours truly

Waynett Campbell