Poland

Basic Data

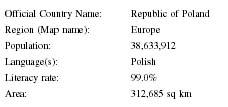

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Poland |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 38,633,912 |

| Language(s): | Polish |

| Literacy rate: | 99.0% |

| Area: | 312,685 sq km |

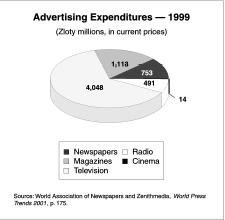

| GDP: | 157,739 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 59 |

| Total Circulation: | 1,157,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 28 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 460 |

| Total Circulation: | 963,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 23 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 836 (Zloty millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 10.80 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 179 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 13,050,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 337.8 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 3,583,620 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 92.6 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 2,500,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 64.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 792 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 20,200,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 522.9 |

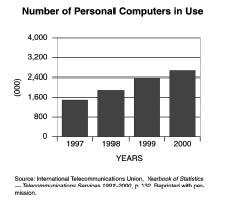

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 2,670,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 69.1 |

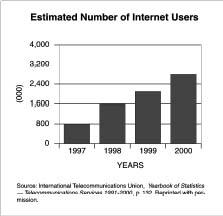

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,800,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 72.5 |

Background & General Characteristics

General Historical Description

Poland reached the pinnacle of its influence in the sixteenth century, when it became one of the most important powers in Europe. At that time, Poland's territories stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea.

When the sixteenth century Jagiellonian dynasty came to an end, the Poles introduced the heretofore-untried governmental strategy of an elected monarchy of kings chosen from royal families. Notable was the Polish introduction of a parliamentary voting system called the liberum veto. In this system any member of parliament could veto a law with a single vote.

The seventeenth century was a turbulent time in Polish history. The Swedes first invaded Poland, then the nation fought a war with the Turks. Poland also experienced a Cossack rebellion in the southeastern territories. Poland slowly crumbled and eventually, at the end of the eighteenth century, Russia, Austria and Prussia divided Poland into three sections.

Poland continued to be occupied during the nineteenth century, despite two uprisings in 1830 and 1863. Independence finally arrived with the end of World War I. Unfortunately, after Poland gained independence it was soon overrun by Germany and the Soviet Union in World War II.

Poland's postwar fate was decided by the Allies at the Yalta Conference held in February 1945. There was no Polish representation at the conference. A Provisional Government of National Unity, made up of members of the pro-Soviet government and émigré politicians was established. Free elections were to be held shortly after the end of the war, but those elections did not occur. A government in exile formed, and Britain and the United States withdrew their support and diplomatic recognition of Poland due to Soviet actions within the country.

Polish borders were greatly altered after the Allied conference in Potsdam, Germany, in 1945. The Soviet Union retained control of the territories it had obtained in 1939, while Poland gained large areas of former German territory in the west including the industrial region of Upper Silesia, the ports of Gdansk and Szczecin, and a long Baltic coastline.

Political strife and labor turmoil in the 1980s led to the formation of the independent trade union Solidarity. Solidarity soon gained a strong political following and with the advent of glasnost in the Soviet Union, was able to rapidly become a robust political entity. After the collapse of the Soviet empire, Solidarity swept parliamentary elections and the presidency in the 1990 elections.

An important role was played by the media in shaping social attitudes that led to the Solidarity movement. Despite censorship and administrative interference, the evolution of the Polish film school in 1956 helped bolster freedom of thought through art. Also of importance to the loosened fetters of censorship was the political, literary and scientific activity pursued by people in exile. Radio Free Europe played a significant role in molding public opinion. Similar roles were played by the Paris-based periodical Kultura and a number of similar publications.

In 1988 Poland experienced a large number of strikes. By 1989 roundtable talks between the authorities and the opposition were arranged and were held with the mediation of the Church. The talks were bolstered by a new world politic. Perestroika in the USSR and the support of the Western states for reforms in Poland helped Polish negotiators bargain.

In June 1988, elections were held that had been agreed upon in the roundtable contract. The Communist Party did not even win the votes of its own members, and retained with difficulty only those offices that had been allocated to it beforehand by the contract with the opposition. The efforts of Lech Walesa and other leaders brought about the first non-communist government in the Soviet bloc.

Privatization programs during the early 1990s enabled the country to transform its economy into one of the most vigorous in Central Europe, boosting hopes for acceptance to the EU. Poland joined the NATO alliance in 1999.

General Characteristics of the Population

About 38 million people live in Poland, and the yearly rate of increase is 4.8 people per 1,000. World War II was cataclysmic to the country as 6 million people—or about one-sixth of the population—died, including nearly 3 million Polish Jews in Nazi death camps.

Around 60 percent of Poles live in a city. There are a number of large cities, including Warsaw with a population of around 1.7 million.

Poland has made significant progress in education. In 1970 about half of the population had a primary education or less. By 1997 that number had dropped to one-third. Also during that time span, the number of college-educated people increased from 2 percent to nearly 10 percent. Educational advancement has been gender-based. Men improved their education largely through vocational training while women tended to obtain a general secondary education. As a result, 57 percent of working women now have at least a general secondary education while 43 percent of working men have a basic technical education.

Although improvement has taken place, Poland still needs to augment its educational system to meet the needs of the twenty-first century. Poland's people still lack skills in information technologies, new ways of organizing industry and job elasticity.

An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Adult Literacy Survey illustrated the gap between Poland and other European countries. The survey revealed that more than 70 percent of Poles did not reach a moderate level of competency, while in all other countries only 32 to 44 percent of respondents failed to do so. The low level of adult literacy in Poland is prevalent for those living in rural areas. Polish farmers had scores 40 percent lower than Polish respondents of other professions. In other OECD countries, farmers' disadvantage was between 9 and 10 percent. Low adult literacy rates in Poland are largely explained by the poor performance of two sizeable groups of Polish respondents, namely farmers and people with basic technical education. These two groups represent about 63 percent of the total working-age (15 to 64) population.

Attempting to obtain higher educational standards entails major effort. The school system in Poland seems to be substandard. The country is characterized by qualms on the final shape of educational reform. In addition, ambiguity about its financing and lack of lucidity on the separation between the state, local communities and other educational partners concerning responsibilities remains problematic. Socio-economic disparity between social groups and regions also may create difficulty in achieving elevated educational norms.

Media History

Transformation in the Polish media sphere began immediately after the collapse of the Communist regime in 1989. On April 11, 1990, Polish parliament passed an anti-censorship act that modified the Press Act of 1984 implemented by the previous communist administration. The structure of Poland's media also was reformed by the Polish legislature. Economic reforms in the print arena gave journalists who had previously worked for state-owned newspapers the opportunity to take over ownership. In addition, foreign investors were allowed to enter the Polish media market.

Electronic media also experienced reformation. First, the transformation of the state-owned broadcasting apparatus into a public company was implemented. Second, policies encouraging commercial radio and television stations were instigated. The Polish government modeled the organizational framework of Poland's electronic media after the French Conseil National dÁAudiovisuel.

Poland enjoys a strong tradition of newspaper publishing. The Press Research Center at Jagiellonian University in Krakow reports that about 5,500 print media periodicals are published in Poland. A menagerie of daily and weekly newspapers of various qualities offers an assortment of opinions to Polish citizens.

Generally, periodicals in Poland can be separated into pre-and post-1989 categories. Papers existing before 1989 established under Communist rule have been privatized and sold to investors, often foreign. Publications that came into being during or after the change of the political system often reflect the values of post-communist Poland.

A strong characteristic of Polish newspapers is they do not attempt to disguise their political sympathies and readers can expect the opinions of editors to be explicitly expressed. In addition, Polish papers often do not separate news from opinions.

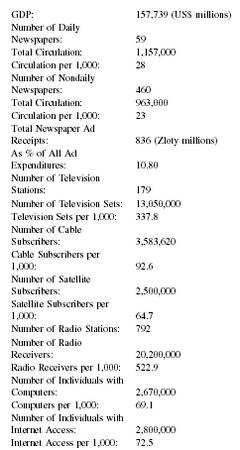

Gazeta Wyborcza is the most widely read newspaper in Poland. It was launched as a venture of the Solidarity movement in 1989. The newspaper was, at conception, owned by the Polish company Agora. Agora was a Polish company founded by the anti-communist movement in Poland. Eventually it was partially purchased by the U.S.-based media conglomerate, Cox Communications. The paper has a circulation of around 600,000.

Other larger dailies in Poland include: the Rzeczpospolita , Super ExpressDziennik Sportowy, Nasz Dziennik, and Trybuna.

Local newspapers in Poland benefit from a circulation of between 7 to 8 percent of the total circulation figures. Poland's industrial regions serve as the crux of the local press industry. Pomorze'Pomerania; Wielkopolska'Major Poland; and Slask'Silesia operate as hubs for the majority of local newspapers that have circulations between 1,000 and 3,000.

Publishers in Poland also distribute 78 regional journals. In addition, a budding magazine sector is gaining readership. Notable, however, is that many major magazines are owned by foreign concerns: Gruner & Jahr/ Bertelsmann, Axel Springer, H. Bauer, Hachette Filipacchi. There are a few local publishers, including: Agencja Wydawniczo-Reklamowa WPROST, Proszynski, S-ka and POLITYKA Spoldzielnia Pracy. Polityka and Wprost are two of the most prestigious news magazines and each has a circulation of around 300,000. Another competitor in the magazine market is the Polish edition of Newsweek. Magazines currently account for about 12 percent of the money spent on advertising, with the European average around 20 percent.

Most sales of newspapers, periodicals and magazines occur at kiosks. Subscriptions represent less than 4 percent of total sales.

The local media in Poland has expanded at a rapid rate since 1989. Three periods may be noted. The first was founded upon widespread support for Solidarity. The second phase was rooted in the dissolution and disbanding of the anti-communist forces. Finally, local media is now based upon profit rather than political thought.

Tendencies in the print media in Poland have been similar to those in other developed countries; however a few differences should be noted. First, there has been a marked drop in the number of readers and circulation of newspapers since 1985. This has been true across Europe with the exception of Portugal, where the starting point for the number of readers was quite low. Magazines have had a different history. The largest difference is the magazine industry's tendency to address specialized, particular products rather than aiming for a mass audience. The number of titles in Polish magazines has increased dramatically—an

Until 1989 Poland had only one broadcaster 'Polish Radio and Television' which was operated by the state. After the fall of the Communist government, television and radio structure changed. First, Polish Radio was separated from Polish Television and both were reconstructed into public service organizations. Commercial interest in radio and television has grown and foreign investment has surged, albeit lower than in print media. This can be explained by legal limitations on Polish media which stipulates that broadcasting companies may not have more than 33 percent foreign ownership.

Economic Framework

Following a period of intense reform efforts in the early 1990s, Poland's was the initial economy in the region to recover to pre-1989 levels of economic output. Growth in the gross domestic product (GDP) since 1993 historically has been strong, averaging more than 5 percent annually, and making the Polish economy among the most robust in Europe. OECD admitted Poland as a member in 1996. Additionally, Poland has met nearly all of the conditions for European Union membership and is expected to be admitted within a few years.

Poland's economic performance has remained relatively good when compared to other post-transition economies. Poland's insistence in engaging in a reform strategy has led to the nation becoming one of the most prosperous in the region. Policies allowing privatization of state-owned companies and statutes allowing the establishment of new business have been followed by rapid development in the private sector.

Key industrial areas including coal, steel, railroads, and energy have undergone restructuring and privatization. However, further progress in public finance depends on privatization of Poland's remaining state sector.

Although Poland's economy is better and more stable than its counterparts in Central and Eastern Europe, the GDP per capita remains inferior when compared to its Western neighbors. Recent analysis indicates that Poland's GDP is little better than half the level of the poorest European Union members. Also notable is that Poland's GDP has leveled in recent years. In the first half of 2000 the GDP was 5.4 percent higher than in the previous year, in the second half that had fallen to 2.7 percent, and dropped again to a lowly 1.8 percent in the first half of 2001.

Poland's economic situation has impacted Polish media. The last half of the 1990s witnessed a number of newly established quality newspapers disappearing from the media market due to harsh economic realities. Their situation was significantly worse in comparison to older, pre-existing newspapers that received higher profits from advertisements. Ironically, the public adjusted to placing advertisements in "old" newspapers even when the circulation of new newspapers was similar. Further, Poland's new government does not subsidize the press, which makes capital from advertising essential to survival.

Press Laws

Since the fall of communism, the major legislation in broadcast media is the Broadcasting Act (Radio and Television Act) of 1992, as well as the Regulation of National Council of Radio and Television which grants and revokes licenses required for broadcasting radio and television programs. The Broadcasting Act of 1992 establishes the National Council of Radio and Television. This institution is designed as an independent body whose most important tasks are to grant and revoke licenses for broadcasting stations, appoint members of supervisory boards for public radio and television, and control and evaluate practice in the audiovisual field. The National Council is patterned after French Conseil National dÁudiovisuel, and its members are elected for six-year terms.

The National Council has granted dozens of licenses both on the national level and the local level. The license procedure is transparent and open to the public. Complaints concerning granting or refusing a license may be brought before the Supreme Administrative Court.

The primary legislation governing the printed press is still the Press Act of 1984 as amended several times, especially in 1990. The Press Act of 1984 now states that the only requirement necessary to start the publishing of a newspaper is registration by the Regional Court. The act also stipulates that state institutions, economic entities, and organizations must provide the press with information. Only when it is required to keep state secrets may entities refuse to provide information.

The Church has attempted to influence broadcast law. Agreements with the government and Polish Radio and Television gave the church favorable access to electronic media as early as mid-1989. The Church pays less than commercial stations for its radio licenses. An ill-defined clause enshrining "respect for Christian values" was controversially forced through by the Church's supporters in parliament as part of the new Radio and Television broadcasting bill passed in December 1992. Poland's government can therefore revoke licenses according to vague criteria about safeguarding Christian values. In the present absence of state censorship, the Church has to take recourse to the rather sparse provisions provided by the press and penal codes. The Church is concerned with prohibiting pornography and obscenity over the airwaves. In August 1995, Trybuna reported that pressure was being exerted by municipal authorities against newstands to restrict the sale of pornographic magazines.

Censorship

There exists a history of censorship in Poland. Before the pre-1918 liberation censorship of materials was common. After liberation in November 1918, censorship was curtailed. However, the state of emergency prevailing over much of Poland, due to numerous wars waged during the first few years of independence, provided rationalization to suspensions of democratic freedoms of the press. The 1920 war against Soviet Russia also brought about the introduction of censorship in defense of military secrets.

Between the two world wars, Poland tended to display little censorship of the press. Legislation in interwar Poland initially granted publishers the ability to print a wide variety of opinion. Furthermore, the 1921 March Constitution codified a variety of press liberties.

After 1926 the Sanacja government became increasingly authoritarian and the unified Press Law of 1927 allowed the use of economic sanctions to curtail press independence. By 1935, the Poland's constitution no longer provided for freedom of the press. The government began to coerce editors to print sympathetic stories and instructed newspapers about what to print. The government and its agents also attempted to dominate the distribution network. In 1928, the government signed an agreement with the Association of Railway Bookshops to exclude publications of a communist nature from its kiosks.

In 1934 a press agreement was secretly signed with Nazi Germany. All works critical of Hitler and other leading Nazis were banned and removed from circulation. Hitler's Mein Kampf was distributed. Further, the Catholic Church occasionally supported repressive measures against specific individuals and works which allegedly offended religious sentiment and public decency.

The invasion by Germany in 1939 brought harsh censorship to the Polish press. Production and distribution of papers were deeply affected in the war, but the impact varied between cities depending on German behavior. In Krakow, for example, the early days of occupation were relatively calm and journalists received permission from the local military authority to publish newspapers, albeit subject to censorship. The inhabitants of Krakow went without papers for only a short while. In sharp contrast, in Czestochowa the German occupation was extremely violent. Media was absent from Czestochowa for months and when newspapers slowly reappeared, the Germans completely controlled their content.

Early in the war and until early 1943, the Polish-language press existed only to communicate German directives. The German occupation government used the press often to remind the Poles of their "sub-human" status. By 1943, recognizing the precarious nature of the war on the eastern front, Joseph Goebbels issued a memorandum recommending that Poles be enlisted in the fight against Soviet Bolshevism. Local government and press leaders were prepared to institute the "reforms" which Goebbels recommended with the hope that this would pacify the Polish population. Examples of the reforms included eliminating malicious statements about Poland and its "national character." The press was to emphasize the "good, even friendly relations" with the Germans. In spring 1943, Germany finally implemented reforms along the lines suggested by Goebbels. By that time, Polish resistance had grown in power, and with the Russians, was defeating the Germans on the eastern front.

After World War II, Russian censorship of the Polish press initially rivaled the Nazi's authoritarian policies. With the creation of the Soviet-backed Lublin government, communists moved quickly to control key areas of cultural activity. Soon, the state's control and accumulation of print works, enforcement of publishing plans, and its development of absolute domination over the publishing process allowed for complete censorship of information distributed by the press. The Soviet-backed government's iron-hand authority—from financing to distribution—would come to determine in every respect the products made available to the public. By 1950 the government had established a near-monopoly in the collection of subscriptions and distribution of periodical publications. This censorship lasted for nearly 40 years.

Key differences in censorship between the 1960s and earlier decades were noticeable, particularly in the streamlining of the system. The Censorship Office received ever more precise, and sometimes contradictory, instructions—the "Black Book"—on a regular basis in the attempt to guarantee the Communist Party a monopoly on information. Access to information or limited freedom to criticize depended on the individual's status in the official hierarchy.

Lessening government censorship was one of the 21 demands made by Solidarity in the Gdansk Agreement of August 1980. Real reforms were beginning to take shape, and by July 1981 new laws were passed which enabled editors to challenge government censorship decisions in the courts. Tygodnik Solidarnosc mounted the first successful challenge in November 1981 and overturned the government's decision to confiscate readers' letters. The 1980 Gdansk agreement reformed much of the censorship process. Certain types of speech and publications, such as orations by deputies at open parliamentary sessions, school-approved textbooks, publications approved by the church and Academy of Sciences publications were no longer subject to government censorship. This legislation partly dismantled the censorship process. However, imposition of martial law in the early 1980s negated these new-found freedoms. Yet, the basic trend during the 1980s leaned toward less censorship, particularly with the advent of glasnost. By 1989 about 25 percent of all newspapers were exempt from preventive control.

Change spread quickly upon the fall of communism. Newspapers were soon privatized and although television has been slower to reform, new technology and Poland's movement toward the European Union tended to lead to diminishing attempts by the government to retain control over broadcasting. There has been, however, with the election of socialist leaders, a move by the government to regain more control of the media.

State-Press Relations

Several present statutes help to outline the Polish government's relationship with the press. Article 14 of the constitution of 1997 guarantees freedom of the press and of other mass media. In addition, the Broadcasting Act of 1992 privatized state radio and television into joint stock companies that eventually led to private commercial radio and television stations. The act also limits foreign ownership in broadcasting entities to less than 34 percent.

The present-day Polish constitution provides for freedom of speech and the press, and the government, for the most part, respects this right. However, there are some marginal restrictions in law and practice.

By statute, an individual who "publicly insults or humiliates a constitutional institution of the Republic of Poland" may be fined or even imprisoned for up to two years. In addition, persons who slur a public functionary may receive up to one year in prison. The most famous case tried under this law found President Aleksander Kwasniewski suing the newspaper Zycie for insinuating the president had contacts with "Russian spies." Additionally, individual citizens and businesses also can use this provision of the Criminal Code. Network Twenty One, which sells Amway products, employed the statute to prevent a broadcast detrimental to its interests. Another case includes talk show host Wojciech Cejrowski, who was charged with publicly insulting Kwasniewski. Eventually Cejrowski lost the case and was fined.

The new criminal code also specifies that speech which "offends" religious faith may be punishable by fines or imprisonment for up to three years. In 1997, the Council for the Coordination of the Defense of the Dignity of Poland and Poles filed charges against the left-leaning newspaper Trybuna for its alleged insults of the pope. The Warsaw prosecutor's office, however, decided to drop the case.

Another statute that restricts the press includes The State Secrets Act that allows for the prosecution of people who betray state secrets. Human rights groups have criticized this law as restraining the fundamental right of free speech.

Protection of journalistic sources also is addressed in the criminal code. The law grants news sources protection except in cases involving national security, murder, and terrorist acts. Further, if the accused is benefited, statutory provisions may be applied retroactively. Journalists who decline to reveal sources preceding the new code's ratification may avoid sanctions by invoking journalistic privilege.

Up to this point there have been no restrictions placed on the establishment of private papers, journals and magazines. KRRiTV (The National Radio and Television Broadcasting Council) has authority in regulating programming on radio and television. KRRiTV also distributes broadcasting frequencies and licenses and apportions subscription revenues to public media. KRRiTV theoretically is to be a non-partisan, apolitical board. Legally members must be suspended from active participation in political parties or public associations. However, since they are chosen for their political allegiances and nominated by the parliament, serious questions often arise concerning board members' neutrality.

Broadcast law states that broadcasting should not encourage behavior that is illegal or hostile to the morality or welfare of citizens. The law requires that programs respect "the religious feelings of the audience and Christian system of values." This law has never actually been seriously tested in the courts.

The Ministry of Communication selects frequencies for television broadcaster to operate. KRRiTV then auctions the frequencies. The first such auction, held in 1994, gave the Polsat Corporation and a few other local entities licenses to operate. Further licenses were granted in 1997 to TVN and Nasza Telewizja.

Two of the three most widely viewed television channels and 17 regional stations, as well as five national radio networks, are owned by the Polish government. Public television tends to be the major source of information. However, satellite television and private cable services are becoming more available. Cable services carry the main public channels, Polsat, local and regional stations, and a variety of foreign stations.

Statutes concerning radio and television require public television to provide direct media access to the main state institutions, including the presidency, "to make presentations or explanations of public policy." Both public and private television provides coverage of a spectrum of political opinion.

In 2002, Prime Minister Leszek Miller's administration earned a reputation as being unfriendly to media. It has taken action to curb the independence and influence of the country's two most prestigious newspapers, Gazeta Wyborcza and Rzeczpospolita, both of which have attempted to hold government accountable. Shortly after taking office, Miller's government reopened a legal clash with Rzeczpospolita, whose ownership is split between a Norwegian publishing company and the state. Prosecutors have introduced criminal charges against three of its senior managers and confiscated their passports. The newspaper argues that the government is attempting to gain control of the papers by not allowing the Norwegian interest voting rights and/or forcing the Norwegians to sell. In addition, the company that owns Gazeta Wyborcza, founded by Polish reformers, wants to purchase shares in a Polish television network. The Polish government has since introduced legislation that would halt private media companies from having interest in both television and journalistic companies. The Polish government is exempt from the provision, which means the state would be free to print its own agenda.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The presence of foreign capital is most visible in the newspapers sector, especially the local/regional market, where a comfortable relationship exists between publishers and foreign investors. Two firms are in the forefront: Passau Neue Presse (PNP, from Germany), and Orkla Media (from Norway).

Twelve dailies and one weekly are fully owned or controlled by PNP. PNP controls papers in regions where it is present. It is estimated that the company's economic activity makes up about 15 percent of the total income in the newspaper sector of the Polish media market. PNP is a multinational corporate media entity controlling 40 percent of the Czech local market, and it has sizable holdings in Austria as well as Germany.

Orkla Media entered the Polish market in 1993 and controls 10 dailies and 18 percent of the Polish newspaper market sector. On each local market, with one exception, the titles owned by Orkla have dominant position.

H. Bauer Verlag specializes in popular television, women's, and teen magazines. Bauer Verlag publishes 11 magazines and controls 12 percent of the magazine market. Bauer also is present on the Czech, Slovak and Hungarian markets.

Axel Springer Verlag has eight titles and controls 5 percent of the magazine market. Springer Verlag differentiates from Bauer Verlag due to the fact that nearly 40 percent of its revenues originate from advertising. Springer also is active on the television and radio market and is one of the leading media groups in Germany.

Cox Enterprises, a U.S. firm, owns 20 percent of the media company Agora, which radically increased its revenues after selling its shares to Cox. Although Cox doesn't have a dominant share, it is the biggest partner in the company. Agora invests in radio (Inforadio and six local stations) and television (Canal Plus Poland).

In television there are two important firms with foreign capital investments: Canal Plus has more than 200,000 subscribers in Poland, while Polish Cable TV (PTK) has 700,000 subscribers.

There is room for further growth in the pay-television market. The pay channel RTL7 was launched in 1997 by the film and television giant CLT-Ufa. It is based outside of Poland and distributed by satellite in order to circumvent Polish restrictions on foreign ownership. However, RTL7 can only muster audience shares in the low single digits. If allowed to broadcast from Poland the share would undoubtedly rise. This is not likely to happen unless the ownership laws that bar foreign companies are changed. The National Broadcast Council is sympathetic to the case and tried without success to raise the maximum foreign ownership stake allowed from 33 percent to 49 percent. This effort failed.

Foreign investors are waiting for Poland's entry in to the European Union, scheduled for 2003. As an EU member, Poland will have to conform to European-wide media laws, and all ownership restrictions will be lifted.

News Agencies

Polish press agencies include Polska Agencja Prasowa (PAP, or Polish Press Agency); Polska Agencja Informacyjna (PAI or Polish Information Agency) and Katolicka Agencja Informacyjna (KAI or Catholic Information Agency). There are a number of small information providers, which also offer wire and photo services.

Broadcast Media

Historical Overview of Broadcast Media

The Polish United Workers' Party (PUWP) believed television had a specific function in a socialist society. Communist Party leaders often attempted to use television as a conduit to transmit socialist and communist ideology to the people of Poland. They soon discovered that television presented a host of problems as propaganda tool. First, party leaders were unable to fully control the content of television. Second, and perhaps more importantly, government leaders did not comprehend how the plethora of televisions functions prevented the party from reaching its goals. Some have suggested that the government's policies regarding television were a contributing factor in the fall of communism in Poland.

There exist several limitations when analyzing television as an element of social change in Poland. Significant is the fact that radio, not television, was the media of choice in Poland. Before 1970 there were fewer than 3 million televisions in Poland. In addition, only one channel broadcast for only a few hours each day, and its quality of transmission left much to be desired. Television coverage was incomplete in Poland until after the early 1970s. Despite these shortcomings, the government still recognized the potential of television as a propaganda tool. Socialist leaders believed that television would bring culture to the masses and would bring village and city closer together.

Party leaders enjoyed some success in the beginning. Surveys indicated that the television viewing population was partial to various programs presenting the party line concerning economic and political topics. Television also broadcast celebrations denoting Socialist holidays.

The government soon discovered that the persuasive abilities of television tended to decrease over time. People also began to doubt the veracity of television reporting. Perhaps the event that most diminished television's credibility was Pope John Paul II's visit in June 1979. The pope's popularity in Poland was not fully understood by the government. As he worked his way across Poland that summer, he addressed hundreds of thousands of people. Polish television attempted to denigrate the visit, and it censored the coverage, belittled the number of people present at masses, and limited the amount of coverage. Polish viewers were incensed.

Characteristics of Broadcast Media Public radio (Polskie Radio S.A.) and public television (TVP S.A.) still rank as most important among broadcast stations. Polish Public Radio provides four national programs: PR 1 and PR3 (for the general public), PR 2 (which features classical music and literature), and education channel Radio Bis. It also incorporates PR 5, which broadcasts abroad on shortwave frequencies, and 17 regional radio stations, each an independent broadcasting company. Public radio also produces programs in ethnic minority languages.

Two national public television channels (TVP, SA) and 11 regional channels operate in Poland. Ethnic minority television programs are also produced in minority languages by regional stations.

Financing for public radio and television comes through a combination of license fees and advertising. With the fall of the communist system, the National Council for Radio and Television has been created to grant frequencies for broadcasting and new broadcasters.

National commercial channels include Polsat TV, TVN (ITI Holdings), and Channel 4. A 24-hour information channel also is operated by TVN. Other channels include Catholic Puls TV, coded RTL 7, Canal Plus, and Wizja TV. About 500 cable television operators exist in Poland with more than 2 million subscribers. The cable operators, by statute, must transmit two public channels.

There is access to various satellites from Poland. The most popular satellite channels are MTV, Eurosport, RTL and the Cartoon Network.

Electronic News Media

The Polish Internet market is growing, and shopping and banking are becoming popular with well-educated Poles. Numerous local and national government Web sites offer information in an assortment of languages.

Most media outlets in Poland have developed Web sites. The electronic database of the Press Research Centre has recorded 1,516 Internet addresses.

However, media advertising via the Internet may be difficult. Europemedia reports that only 24 percent of Polish firms consider advertising on the Internet to be better than advertising via traditional media. Further, according to research conducted by the Krakow Academy of Economics, 48 percent of Polish entrepreneurs believe that advertising through traditional media is superior to online advertising. However, while Polish firms are skeptical about online advertising, more than half of the companies surveyed claimed they would "definitely" be using the Internet in the future to promote their products.

Education and Training

Polish journalists are, for the most part, well educated and competent in their craft. Many hold college degrees but this is not a requirement.

The major media employers' organizations are: the Polish Chamber of Press Publishers, the Association of the Local Press Publishers, the Convent of Local Commercial Radio Stations, the Association of Independent Film and TV Producers and the National Industrial Chamber of Cable Communications, the Polish Journalists Association (SDP), the Journalists Association of the Republic of Poland (SDRP), the Catholic Association of Journalists, the Syndicate of Polish Journalists, the Union of Journalists, the Union of TV and Radio Journalists, the European Club of Journalists, the Local Press Association, the Polish Local Press Association, the Polish Chapter of the Association of European Journalists.

A code of ethics was adopted on March 29, 1995, in Warsaw by most of these organizations. The code stated that journalists should perform their craft in accordance with the principles of truth, objectivity, dividing commentary and information, honesty, tolerance, and responsibility.

Summary

A multitude of media voices exist in Poland and most are tolerated. Videotapes are available in local stores, and comics, once heavily influenced by government intervention, are free to portray a variety of political stances. Polish law now allows competition for state owned radio and television. Further, several private newspapers have commenced publishing. Privatization has become the hallmark of Polish post-communist culture. In Poland during the first year after the fall of communism, the number of journals and newspapers increased by 600 in five months. More than just creating new publications, the Poles began to provide avenues for publishing. New publishing companies were formed to replace the Robotnicza Spoldzielnia Wydawnicza (RSW, the Workers Cooperative Publishing House), the organization that had control over 80 percent of Polish publications for 40 years.

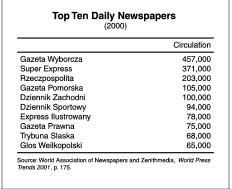

Television growth in Poland has been explosive as well. The total advertising money spent virtually doubled between 1997 and 1999, from 3.7 billion zlotys (U.S. $840 million) to 7.3 billion zlotys (U.S. $1.67 billion). Poland is one of a number of countries in Europe where private stations have to compete for both audiences and advertising revenue with subsidized state-owned channels.

The media in Poland remains in an expansionist mode. Polish media is taking on a global dimension with the introduction of digitalization, specialization, concentration of media ownership, and development of local media.

The rapid growth of Polish media may also have some detrimental consequences. The media companies now existing in Poland must be willing to work diligently to develop new strategies in order to hold their place in the market. The concentration of media ownership, as big media conglomerates buy weaker publishers and stations, may become problematic. Locally, newcomers to the profession may not be as experienced or well trained. Finally, the demand for sensationalism has grown and may lead to inferior coverage of newsworthy events.

Polish media has experienced tremendous change since 1989. Privatization has been leading Poland away from an ideological to a market-driven media model. This could lead to Polish media being dominated by corporate interests as media conglomerates gain a larger share of the media. However, there is a possibility that privatization will cease. The Polish government has become less friendly to foreign investment. The government seems to be giving up and even reversing previous plans for privatization in the media sector.

Poland has attracted the largest amount of foreign investment among European Union candidate countries: 36 billion euro. The sale of hundreds of companies has made it possible to substantially change telecommunications. This has enabled an injection of not only capital, but also new technology and management methods of key importance for the process of restructuring Poland's media industry.

Polish media is sitting upon the threshold of a new era. The path it chooses to tread will be directed by economic and political forces both inside and outside of Poland.

Important Dates

- 1984: Polish Press Act

- 1989: Industrial unrest and economic problems lead to Round Table Talks between the government and the opposition.

- 1989: In partly democratic elections, Solidarity wins a landslide victory; Tadeusz Mazowiecki becomes the first non-Communist prime minister.

- 1990: The name of the country is changed back to "Rzeczpospolita Polska" or "The Republic of Poland."

- 1990: The Polish Communist Party ceases to exist.

- 1990: First democratic presidential elections; Lech Walesa elected president.

- 1990: Anti-Censorship Act introduced.

- 1992: Radio and Television Broadcasting Act introduced.

- 1993: A coalition of leftist parties gains control of the Sejm, the Polish parliament.

- 1995: Aleksander Kwasniewski, a leader of the leftist coalition and former communist, is elected president. He promises to continue reforms and integration with free Europe.

- 1997: Constitution adopted including Article 14 which guarantees freedom of the press.

Bibliography

Bernhard, Michael H., ed., et al. From the Polish Underground: Selections from Krytyka, 1978-1993. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995.

Bates, John M., "Freedom of the Press in Interwar Poland: The System of Control," Peter D. Stachura (ed.), Poland between the Wars, 1918-1939, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998, pp. 87-108.

——. The Black Book of Polish Censorship, New York, 1984.

Casmir, F. L., ed. Communication in Eastern Europe: The Role of History, Culture, and Media in Contemporary Conflicts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1995.

Central Europe online. Available from www.europeaninternet.com/centraleurope .

Choldin, Marianna T. A Fence Around the Empire, Durham, USA: Duke University Press, 1985.

Ciecwierz, Mieczyslaw. Polityka prasowa 1944-1948, Warsaw:PWN, 1989.

Committee to Protect Journalists. "Country Report: Poland." Committee to Protect Journalists: 2000. Available from www.cpj.org/attacks99/europe99/Poland.html .

Davies, N. God's Playground, 2 vols, Oxford: OUP, 1981.

Dobroszycki, L. Reptile Journalism: The Official Polish Language Press Under the Nazis, 1939-1945. Yale University Press. New Haven, CT, 1995.

Eastern European journalism: before, during and after communism. Cresskill, N.J.: Hampton Press, 1999.

Garton Ash, Timothy, ed. Freedom for publishing, publishing for freedom: the Central and East European Publishing Project. Budapest: Central European University Press, 1995.

Giorgi, Liana. The Post-Soviet Media: What Power the West? The Changing Media Landscape in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. Aldershot, England; Brookfield, Vt. : Avebury, 1995.

Kondek, Stanislaw A. Wladza i wydawcy, Warsaw: Biblioteka Narodowa, 1993.

Leftwich Curry, J. Poland's Journalists: Professionalism and Politics, Cambridge, 1990.

Loboda, J. Rozwój telewizji w Polsce, Wroc?aw, 1973.

——. The Media and Intra-Elite Communication in Poland (4 volumes), Santa Monica, 1980.

Monroe's Post-Soviet Media Law Review. Available from www.vii.org/monroe .

Notkowski, Andrzej. Prasa w systemie propagandy rzadowej w Polsce 1926-1939, Warsaw-Lodz: PWN, 1987.

O'Neil, Patrick, ed. Post-Communism and the Media in Eastern Europe. London: Frank Cass, 1997.

OECD. "Adult Literacy Survey." Available from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs97/9733.pdf .

Pietrkiewicz, Jerzy. "'Inner Censorship' in Polish Literature," SEER , 1957, vol. XXXVI, no. 86, pp. 294-307.

Sparks, Colin, and Anna Reading. Communism, Capitalism and the Mass Media. London: Sage Publications, 1998.

Szydlowska, Mariola. Cenzura teatralna w dobie auto-nomicznej 1860-1918, Cracow: Universitas, 1995.

Terry Robertson