South Africa

Basic Data

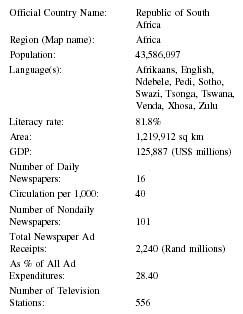

| Official Country Name: | Republic of South Africa |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 43,586,097 |

| Language(s): | Afrikaans, English, Ndebele, Pedi, Sotho, Swazi, Tsonga, Tswana, Venda, Xhosa, Zulu |

| Literacy rate: | 81.8% |

| Area: | 1,219,912 sq km |

| GDP: | 125,887 (US$ millions) |

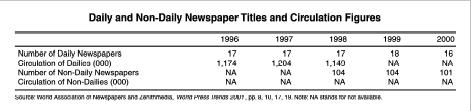

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 16 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 40 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 101 |

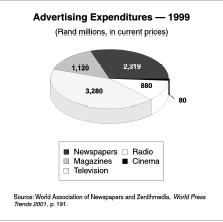

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 2,240 (Rand millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 28.40 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 556 |

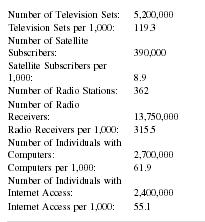

| Number of Television Sets: | 5,200,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 119.3 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 390,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 8.9 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 362 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 13,750,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 315.5 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 2,700,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 61.9 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,400,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 55.1 |

Background & General Characteristics

South Africa, which covers 470,462 square miles of the southern tip of the African continent, is home to more than 43 million people. It is bordered by Namibia in the northwest, Zimbabwe and Botswana in the north, Mozambique in the northeast, Swaziland in the east, and the Indian and Atlantic oceans in the south, southeast, and southwest. The small Kingdom of Lesotho is completely surrounded by South Africa.

South Africa is probably the only country in the world to boast four capital cities. Johannesburg, the country's largest city, is the commercial capital. It is located in the midst of the country's gold and diamond mining industry. Nearby Pretoria is the country's administrative capital. Cape Town is the legislative capital, where the South African Parliament meets. Bloemfontein is the country's judicial capital.

South Africa is considered one of the most developed countries in Africa. According to the 2001 Global Competitiveness Report , South Africa was ranked number 34 in the world in terms of national economic growth prospects, placing it in the upper echelons of world countries. This also made it the highest ranked African country in that category. Some have said white South Africans belonged in the Second World in terms of economic growth, industrialization, and prospects, while the country's African majority pulled the country into Third World membership.

Literacy is more than 90 percent for whites and about 60 percent for blacks, directly affecting newspaper read-ership. The average annual income is US$3,170, but this figure is somewhat misleading because whites make up to 10 times more than their black counterparts.

South Africa has a varied racial and ethnic makeup. For much of its recent history, whites dominated its political, economic, and military setup. Coloreds (mulattoes or those of racial mixed descent), Asians (mostly Indians, Pakistanis, and Chinese), and some Arabs, served as a buffer between the whites who occupied the top rungs of the ladder and the black majority, which was exiled to the lowest rungs of the ladder. Today, South Africa's population is 75 percent black Africans, 14 percent whites, 9 percent coloreds, and 2 percent Indians and other races.

English is the official language. Most whites speak English or Afrikaans. Many Africans speak English, some speak Afrikaans, and all of them speak African languages, especially Zulu, Xhosa, Ndebele, Pedi, Tsonga, Sotho, Swazi, and Tswana. South Africa has 11 recognized languages, including English and Afrikaans. South African radio and television broadcast in the 11 recognized languages. Most newspapers, however, are published in English and Afrikaans. Those that cater to the African majority are almost entirely in English, since many Africans refuse to speak Afrikaans, which they regard as the language of their former oppressors.

History

South Africa is an old country, but its modern, recorded history is sometimes traced to the trade between European sailors who were plying the route to India. Under white rule, it was claimed that Portuguese navigators Bartolomeu Dias, in 1488, and Vasco da Gama, in 1497, were among the first European sailors to sail around the southern tip of South Africa. The Portuguese, therefore, were the first Europeans to establish a presence at what would become known as the Cape of Good Hope, which was central to the route between Europe and India. They were followed by the Dutch, who were also on their way to the east, when they decided to establish a presence at the cape. Unlike the Portuguese, who remained on the coast, the Dutch began to move inland. More Europeans followed, establishing the Cape as an integral part of trade with the East. French Huguenots, fleeing religious persecution in Europe, arrived at the Cape and began to establish settlements, all without consulting with the indigenous Africans in the surrounding communities, which would lay the seeds for future conflicts.

By the 1770s, the northward expansion of the white colonialists began to produce clashes with the indigenous Africans. For a while, the British controlled the Cape and Natal provinces, while those of Dutch and French Huguenot descent occupied what became known as Transvaal and Orange Free State. As diamonds and gold were discovered in South Africa, the white population continued to rise. War was inevitable, as English immigrants and their Dutch counterparts clashed. Britain was victorious, leading to the creation of the Union of South Africa, as a white-ruled self-governing entity. Also at this time, in 1912, the South African Native National Congress was formed to champion the views and interests of the African majority, whose presence was ignored as the whites fought among themselves. By 1923 the South African Native National Congress was transformed into the African National Congress (ANC), which is today's ruling party.

In the early years of the struggle, however, the fight was between English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking whites. Afrikaans was the guttural language founded by whites from the Netherlands, Germany, and the French Huguenots. It was distinctly different from English. It also served to separate Afrikaans speakers from their English-speaking counterparts.

Until World War II, the United Party was dominated by English speakers, who were also better educated and were running the government, commerce, and industry. Although they had no clear policy over what to do about the black majority, by South African standards the United Party was considered moderate in its treatment and views of the African problem. United Party domination of South African politics ended in 1948 when the National Party won that year's elections. Voting then was limited to whites. Blacks had no political role within the white-dominated system. The National Party was dominated by Afrikaners, who were mostly farmers and miners. They wanted to create a white-dominated country in which blacks had no part. They named their system apartheid, which meant separate racial development. Under apart-heid, South Africa was divided into separate and unequal communities.

Under apartheid, blacks were denied South African citizenship. All political, economic, industrial, agricultural, military, and social power resided in the hands of the white minority. Blacks working as miners, domestic workers, factory, and farm hands were regarded as immigrants who were available as temporary workers, who could stay in the white areas as long as their labor was needed. They could not vote, could not organize or strike, could not build homes in the urban areas, and could not compete for jobs set aside by law for whites.

The National Party's agenda was to force all blacks to become citizens of what came to be known as "Black Homelands." These were largely barren pieces of land, with no cities, often no electricity, no industry, and no mines that were randomly established in remote parts of the country. These homelands would one day become "Independent States" where Africans who collaborated with apartheid could rule their own people. Most black South Africans, including Nelson Mandela of the African National Congress, rejected apartheid and independent homelands and instead demanded a unitary South Africa that accepted all South Africa, regardless of race, color, ethnicity, creed, or national origin. Most blacks, led by the ANC, its rival, the Pan-Africanist Congress, and other militant groups categorically and unconditionally rejected the homeland solution, insisting instead on their South African citizenship.

These were the conditions South Africa faced as the 1980s ended. South Africa was confident that with its strong and well trained military, police, and undercover forces, it could hold on to power indefinitely and keep the black majority oppressed. There was no immediate fear that the ANC and its allies could militarily overthrow the apartheid regime, at that time led by P.W. Botha and his National Party. It was also equally clear that the ANC, although banned, enjoyed massive support among black South Africans and that it was capable of continuing indefinitely its low-level campaign of guerrilla warfare and sabotage.

The South African economy was suffering, Mandela had been transformed into an international icon, and foreign governments were pressuring Pretoria to end apart-heid. With Zimbabwe independent and Namibia following suit, South Africa faced increasing international isolation, while the ANC was gaining more allies and more territory from which to operate. Some of South Africa's leaders were beginning to warn South Africa that unless it scrapped apartheid, there was no chance of the country ever gaining international acceptance and recognition, that its economic plight would worsen as multinational companies were forced to leave the country and banks became more reluctant to lend money to South Africa. It was clear the ANC was winning the battle for the minds of black South Africans, as well as economic, diplomatic, and political support from the international community.

Botha had been replaced as ANC and South African president by F.W. de Klerk, who proved to be a much more pragmatic leader. In 1989 De Klerk stunned South Africa and the world, by unconditionally releasing many senior ANC leaders; Nelson Mandela, by then the world's best-known political prisoner, left prison on February 11, 1990—27 years after he had been incarcerated. A new South Africa was dawning. In September 1989, the South African government announced that the banned African National Congress, the Pan-Africanist Congress, and the South African Communist Party and other anti-apartheid groups were no longer banned, almost 30 years after they had been initially banned.

De Klerk proposed a new political dispensation in which blacks and whites would be treated as equals, with equal political rights for all. He scrapped all apartheid rules, laws, and policies, and ended the political chasm between the ruling white minority and the black majority. He dared to negotiate with Mandela and others to bring about a democratic, multiracial South Africa. Mandela and De Klerk jointly won the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts in bringing about a new South Africa that was no longer a prisoner to its apartheid past. Mandela and De Klerk became the country's co-leaders until the country's first democratic and multiracial elections in April 1994. As expected, the ANC won with 62.7 percent of the vote, followed by the National Party at 20.4 percent; the Inkatha Freedom Party won 10.5 percent. The radical Pan-Africanist Congress and other smaller white and black groups shared the remaining votes.

During elections held June 1999, the ANC again swept the field. Mandela's deputy, Thabo Mbeki, became the country's second democratically elected president. Mbeki is expected to serve until 2004, when he is likely to run for a second and final term as South African president. In less than 10 years, South Africa has been transformed from an exile nation to one that is internationally accepted and looked upon as a beacon of democratic hope and opportunities.

Media History

The media history of South Africa can be divided into two main phases: during apartheid and after apartheid. These two categories define the fundamental changes that have reshaped South Africa since it was reaccepted into the international community of nations. South Africa is also different from other countries in Africa because of its long tradition of newspaper journalism that dates back to when the whites arrived at the Cape of Good Hope. It is also worth noting that South Africa and Nigeria are the only two African countries with a history of competing newspapers under multiple ownerships.

Almost all South African newspapers are published in English or Afrikaans. The English newspapers generally tend to be more influential and are read by more people. Radio and television, through the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) is in English, Afrikaans, and the country's nine African languages. English is the official language and the language of business and commerce. South Africa wants to be sure that its SABC electronic services reach those who are fluent in many of the country's non-white languages.

The media changes that occurred in South Africa were so dizzying that even some of the editors and journalists had a hard time adapting to the changes. Under apartheid, the media operated in a minefield of laws designed to make it almost impossible to publish any information without authorization from the government, especially on political and national security issues. Newspapers were prevented from publishing the names of banned people, who included almost all the anti-apartheid leaders. Names and pictures of people such as Nelson Mandela disappeared from news pages, as did the names of banned organizations and groups. When South Africa rejoined the community of nations after the end of apartheid, it had a new constitution that protected freedom of expression and of the press. South Africa had moved from having one of the most oppressive media systems in the world to one where the media could publish almost anything, without fear of punishment from the government. The press in South Africa today is free to criticize the government and to publish articles about opposition groups, even when those views are harshly critical of the ANC and its government.

The earliest South African newspapers can be traced to the days of the earliest white settlements in South Africa, especially around the Cape of Good Hope, around the mid-1600s. Those early papers were written and edited by whites for whites; they included stories from England, the Netherlands, France, and Germany—the home countries of the whites who settled in Africa. There was virtually nothing in those early newspapers about the indigenous people. Therefore, it was not surprising that virtually all the early South African newspapers were in English or Afrikaans, the two languages spoken by the dominant white groups in the country. Over time, the number of newspapers rose to 12 in English and 4 in Afrikaans, reflecting the dominance of English and English-speaking whites in early South Africa, even though in terms of population there were more Afrikaners than their English counterparts. Even some of the Afrikaners also preferred to read the English language press.

The first newspaper published in sub-Saharan Africa appeared in Cape Town in 1800. The Cape Town Gazette and African Advertiser , which carried English and Dutch news, began appearing almost 150 years after the first Dutch settlers had arrived in South Africa. It was the arrival of British settlers, however, that seems to have resulted in the publication of the country's first newspaper. Despite initial opposition from colonial authorities, eventually the paper began to enjoy a measure of freedom and autonomy. This was followed by the appearance, in 1869, of another newspaper in the Cape area, when diamonds were discovered in the region. Not to be outdone, in 1876 Afrikaners began publishing their own newspaper, called Di Patriot . Die Zuid Afrikaan , a Dutch language newspaper, began publishing in Cape Town in 1828.

The continuing political problems between those of English and Dutch descent spilled over into the media arena. Those of Dutch descent were unhappy about being under British influence and control. When the Dutch moved north, they also decided to establish newspapers in the areas that fell under their control. To promote and protect their interests in the mining areas, the Dutch descendants two more newspapers, De Staats Courant in 1857 and De Volksten in 1873.

As the number of white settlers in South Africa increased, chain newspapers arrived in South Africa with the launch of the Cape Argus in 1857 and Cape Times in 1876. As relations between the Dutch and the English speakers worsened, the press became more partisan, taking sides in the disputes between the two groups. But after the 1889-1902 Anglo-Boer ended, with the English victorious, the Union of South Africa was born, which brought together English-speaking Natal and Cape Town on one side with the Dutch republics of Transvaal and Orange Free State.

By the time this came about, English-language and Dutch language newspapers were pretty much in place. On the English side were the Eastern Province Herald , first published in 1845; the Natal Witness , 1846; the Natal Mercury , 1852; the Daily News , 1854; The Argus , 1857; Daily Dispatch , 1872; Cape Times , 1876; Diamond Fields Advertiser , 1878; and The Star , 1887.

The first non-English and non-Dutch newspapers also emerged at this time, with Indian Opinion in 1904; and two African newspapers, Imvo Zabantsundu in 1884 and Ilanga Losa in 1904.

Although aimed at English-speaking merchants, professionals, and civil servants, the English press also found some ardent readers among the Dutch. This was also the time that the English press established its dominance in many of South Africa's largest cities. Among such newspapers was the Rand Daily Mail , which was founded in 1902. For a while it became one of the most influential newspapers in South Africa. The South African Associated Press , now Times Media , became the biggest chain of Sunday and daily morning newspapers in the country.

Meanwhile, there was a parallel movement among the Dutch descendants, who founded newspapers to promote their political, economic, and cultural interests. The Dutch felt oppressed by the English, after losing the Anglo-Boer war, so they started Die Burger in 1915 to promote their interests. Die Burger was a different kind of newspaper because it depended on support from numerous small shareholders. It had links to political interests, especially to the National Party, which ruled South Africa from 1948 until apartheid was dismantled. Die Burger also was influential in the founding of National Pers , which is now South Africa's second largest newspaper chain. Perskor , a second Afrikaans newspaper chain, appeared in Transvaal in 1937. It also supported the National Party and promoted its political agenda, language, and culture.

During the days of apartheid and since that time, alternative newspapers have made their appearance in South Africa to challenge the country's emergency, censorship,

Among the more prominent such publications were the English language Weekly Mail and Sunday Nation and the Afrikaans language Vrye Weekblad and South .The Weekly Mail had a circulation between 25,000 and 50,000. These alternative publications played a crucial role in the waning days of apartheid because they provided an alternative point of view and were a source of information on the thinking and activities of those groups that sought to dismantle apartheid and everything it stood for. They also played another equally important role, by showing blacks and other anti-apartheid groups that not all whites were monolithic and unquestioning supporters of the idea of forced racial segregation and separate racial development.

However, the end of apartheid was not good news for such publications. Foreign funding largely dried up. Such publications could no longer sell themselves or attract attention because of their anti-apartheid views. Among the survivors, however, is the Weekly Mail , which now calls itself the Weekly Mail and Guardian . It is still an alternative to the mainstream media with criticisms of the ANC government

Influential Newspapers

It is estimated that more than 5,000 newspapers, journals, and periodicals are produced regularly, almost all of them using the most modern technology and equipment. The Johannesburg Star , an English language daily paper, has a circulation in the 200,000 to 250,000 range. It is one of the best circulating newspapers in sub-Saharan Africa and is South Africa's largest and most influential newspaper. It is, by far, the most influential newspaper in South Africa. The Star is part of the Argus Group, the biggest publishing company in South Africa and, indeed, in all of Africa. It has publishing interests in other African countries. At one time, it owned the single largest stable of daily, weekly, and Sunday newspapers in Zimbabwe, although these were later sold to the government-controlled Zimbabwe Mass Media Trust.

Another influential newspaper in South Africa is the Sowetan , an English language black newspaper that circulates primarily in Soweto, a sprawling Johannesburg township, and in Johannesburg proper. The Sowetan , established in 1981, has a daily circulation in the 200,000 to 250,000 range. Most of its readers are blacks. Despite that, it has not been afraid to take on and challenge the ANC government led by Mbeki.

Other influential South African newspapers include Beeld , a daily Afrikaans language newspaper published in Johannesburg, and Die Burger , an Afrikaans daily published in Cape Town. Both Beeld and Die Burger have daily circulations in the 100,000 to 125,000 range. They are the two largest and most influential Afrikaans newspapers in South Africa.

The Sunday Times , an English language newspaper published in Johannesburg, has a circulation in the 450,000 to 500,000 range. It is the largest and most influential weekly paper in South Africa, and it is also the largest Sunday paper in sub-Saharan Africa. Behind it in Sunday circulation and influence is the Sunday Tribune , published since 1937 with a circulation in the 100,000 to 125,000 range.

The City Press , an English language weekly established in 1983 in Johannesburg, has a circulation in the 250,000 to 300,000 range, while the Rapport , a weekly Afrikaans language paper established in 1970 in Johannesburg, circulates 250,000 to 300,000 newspapers. Both of these are considered influential among Afrikaners.

Economic Framework

South Africa is a rich country. It is one of the world's major producers of gold, industrial, and gem diamonds, and it has the world's largest-known gold reserves. De Beers, a South African-based company, has a monopoly on the global sale of gold and diamonds. About 80 percent of the world's known manganese reserves are in South Africa.

South Africa also has a well-developed agricultural sector that includes corn production and cattle ranching. Agriculture is also a major employer, although both it and farming have employed workers from neighboring African countries, especially Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Chemicals, food, textiles, clothing, metals, transportation, communications, roads, and railways are also important to the South African economy and labor force. As a result, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) became politically and economically muscular. It is allied with the ANC, which operated through COSATU during apartheid days to pressure the Pretoria regime through strikes and other labor actions. Even today, COSATU has not hesitated to use its power to wring concessions from its ruling ANC allies.

In June 1988 COSATU and its allies had defied the apartheid regime and staged a massive strike, supported by more than 2 million black workers, which brought the country to a standstill. Soon after that, P.W. Botha resigned as president of South Africa and the National Party.

Newspaper Chains

South Africa has four major newspaper chains: Argus Newspapers, which accounts for 45 percent of all daily South African newspaper sales, especially in the major cities. Its properties include its flag-ship property, The Johannesburg Star , The ArgusThe Cape Times , the Daily News and Natal Mercury , and the Pretoria News and the Sunday Tribune . Next, in terms of size and influence, is Times Media, formerly South African Associated Newspapers, the country's second largest English language newspaper chain. Its other properties include Business Day , the Eastern Province Herald , and the Evening Post in Port Elizabeth. The Sunday Times is also part of the Times Media stable. Times Media is ultimately owned by the giant Anglo-American Corporation, the country's largest company.

The two Afrikaans language chains are Nasionale Pers (Naspers, whose properties include Beeld , Die Bur ger , and Die Volksblad . Naspers also has a 50 percent share in Rapport and also owns City Press , a large Sunday paper that targets black readers. Meanwhile, Perskor the second largest Afrikaans chain, also has a 50 percent interest in Rapport , and it owns The Citizen , a politically conservative English language.

Censorship

The National Party used censorship freely to control what the media published. The Publications Act of 1974 gave the South African government the power to censor movies, plays, books, and other entertainment programs, as well as the right to decide what South Africans could or could not view. Books critical of apartheid or racial discrimination were routinely barred. Movies showing interracial relationships were banned from television and from the movies. The National Party government had appointed itself as the guardian of public morals and behavior.

The new constitution did away with these old behaviors. Censorship laws, policies, and regulations from the apartheid era were scrapped. South Africa, which had become notorious because of its prudish standards, was now open to all types of media, movies, and entertainment. Writers and producers no longer have to worry about censorship or how to beat it. The government has basically left it to the public to decide what it wants to see or read.

Because the new South African constitution protects freedom of expression and of the media, South African Broadcasting Corporation employees are finally free from the strictures and controls imposed on them during the apartheid days. Although the South African government appoints the SABC board of directors, it has not tried to choose only those who support its policies and programs. This has produced an ironic situation where the ANC has allowed and tolerated the use of SABC for the airing and exchange of various views, including those whose views are anathema to the ANC government. So far, South Africa has escaped a problem afflicting many African countries—where presidents and their governments have taken over radio and television and used them as propaganda agencies, often denying opposition groups, parties, and critics access to the airwaves, even when the broadcast media are subsidized by license fees and public funds. So far, the ANC government has resisted the temptation to interfere with the running and programming of SABC television and radio.

State-Press Relations

Under apartheid, the government controlled the media. The government decided what was news. For example, if a journalist witnessed a shootout between security forces and guerrilla fighters, that story could not be reported until it was verified or confirmed by official sources. If the journalist saw bodies of slain soldiers or police officers, he or she could not report that information until it came from official sources. If the police or army denied that any security force personnel had been killed or wounded or that the skirmish had occurred, then such news, regardless of how much information the journalist had, could never be published or broadcast.

During apartheid, foreign and domestic journalists operating in South Africa had to walk through a minefield of legislation designed to prevent the independent publication of information that might embarrass the government. It was the job of journalists and editors to check the laws before deciding what information could be published. Many journalists were reduced to self-policing and self-censorship to avoid breaking the law. Fines, imprisonment, even banning awaited those publications that dared break or challenge these laws. Under the new constitution, South African media and journalists are enjoying unparalleled freedoms. Except for libel laws, they are free to publish any type of news, without having to worry about what laws they may be violating.

In most other African countries, the government has instituted a domestic news agency to serve as the procurer or disseminator of news from other parts of Africa and/or the world. The South African Press Association (SAPA), the country's domestic news agency, transmits about 100,000 words of domestic and foreign news daily to its members. Additionally, the Associated Press (American), Reuters (British), Agence-France Presse (French), and Deutsche Presse-Agentur (German) operate from South Africa. SAPA also cooperates with the Pan African News Agency (PANA), an organization that receives news from all over the continent to distribute within the country. SAPA also sends South African stories to PANA for distribution to other African countries.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

South Africa always has welcomed the foreign media, except when articles critical of apartheid (during the days of apartheid rule) were published. At the height of the apartheid era, many African, American, and European journalists and editors were placed on a prohibited list. Those who had written or published articles critical of apartheid and what it stood for often found themselves unable to obtain visas to visit South Africa.

In the 1980s and 1990s, apartheid was a major story. Many American newspapers, including The New York Times , Christian Science Monitor , the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post , had correspondents permanently stationed in South Africa. Many European journalists were also in South Africa. The major American television networks (ABC, CBS, and NBC) also had correspondents stationed in South Africa or in nearby countries.

Time and Newsweek also sold their magazines in South Africa. South Africans could listen to news broadcasts from the Voice of America, the British Broadcasting Corporation, and other Western short wave radio outlets. The ANC and its allies also had access to radio waves in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Tanzania, and other countries from which they broadcast messages to their colleagues in South Africa. Although it was illegal to listen to such broadcasts, many people tuned in to them.

The Mbeki government has allowed the Voice of America, the British Broadcasting Corporation, and other international broadcast media, as well as journalists from the world's print media, to come to South Africa and to operate freely, even when they sometimes highlight embarrassing stories—such as the one about the government's failure or reluctance to confront the HIV/AIDS pandemic that has ravaged that country. Laws from the apartheid era, which controlled, censored, and intimidated journalists, have disappeared. Foreign journalists and media are freely welcomed in South Africa today and given access to government officials. They are also able, without licensing or accreditation, to roam freely around the country, interviewing whomever they want.

Broadcast Media

Radio and television remain the main means of getting news and information in South Africa. Radio started in South Africa in 1923. Since then, it has spread throughout the country. The South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) was established in 1936 to handle the country's broadcast needs. Over the years, radio was used as a propaganda instrument to force South Africans to accept apartheid and everything it stood for. For a long time, until the 1990s, blacks and others who opposed apartheid were regularly denied access to the country's public airwaves. After the 1960s, the ANC, the PAC, the Communist Party, and other groups that opposed apart-heid could not be mentioned, except derogatorily, on South African radio. They were banned from ever being mentioned, as SABC became more and more part of the government's propaganda machinery.

Even though anybody who owned a radio or television outlet in South Africa was required to obtain an annual listening license, the apartheid rulers saw nothing wrong with using the airwaves to support their National Party and to air nothing but apartheid propaganda. South African Radio today tries to cater to the various interests of its diverse population. It broadcasts in English, Afrikaans, and many of the major African languages.

Radio stations reach virtually every corner of the country. About 12 percent of airtime is set aside for news. In addition to the broadcasts in English, Afrikaans and selected African languages, there is a youth-oriented commercial station and Radio RSA (Republic of South Africa), also called the Voice of South Africa. Radio RSA externally broadcasts 177 hours a week in English, French, Swahili, Tsonga, Lozi, Chichewa, and Portuguese to audiences in other parts of Africa. South Africa is one of the few African countries to allow privately-owned commercial radio broadcasts. Radio 702 and Capital Radio 604 operate outside of the confines of the SABC and, in fact, compete with it. There are also plans to offer more privately owned outlets.

Television came late to South Africa because of the government's fears over what were seen as its corrupting influences. The first TV broadcast was in 1976, long after it had reached many developing African countries. Like radio, television is under the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), which collects license fees from viewers and listeners. There are three major channels: TV1, which broadcasts daily in English and Afrikaans; Contemporary Community Values Television (CCV), which has programs in African, Asian, and European languages; and National Network Television (NNTV), which specializes in sports and public service programming. SABC television fare comes from local programming, as well as programs coming from the United States and Britain. Many of its programs, especially the talk show variety, are borrowed from similar series in the United States.

Electronic News Media

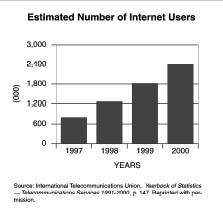

South Africa is among the best African countries in providing its citizens with Internet access. As of 2000, there were 44 Internet service providers.

Education & Training

South African colleges and universities, newspapers, and American and British foundations have been the main sources for the training of future journalists. Many of the leading universities do offer journalism programs and degrees. Workshops and seminars have also been held in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and other African countries to offer training in environmental, economic, and investigative reporting.

Summary

The future looks very bright for the South African media. A new constitution protects a Bill of Rights and also guarantees freedom of expression and of the media. Although the Mbeki government has been unhappy about how it has sometimes been treated by the media and how the president has been caricatured, there has been no attempt to censor or punish the media or to pass laws to regulate the media or to prevent them from doing their job of making the government accountable for its actions. The South African media are emerging from their days of battling and suffering under apartheid laws to become true defenders of media freedom in a democratic society.

Today's South African journalists now operate in a country where they are free to criticize the government, scrutinize its actions, and even make fun of the country's political leaders—without the prospect of prison and hefty fines hanging over their heads. South Africa has emerged from being a journalistic pariah to one of the freest and most democratic countries in the world. The experience has been dizzying for the media, the public, and the new government. The public seems to have become more accommodating to the idea that journalists have a duty to be responsible, without betraying their values, training, and commitment to being the purveyors of information and news, to a public that needs to be informed, educated, and entertained.

Bibliography

"Africa South of the Sahara." Europa World Survey , 2002.

British Broadcasting Corporation. Country Profile: South Africa , 2002.

Davis, Stephen M. Apartheid's Rebels: Inside South Africa's Hidden War . New Haven: Yale University Press,1987.

Faringer, Gunilla L. Press Freedom in Africa . New York: Praeger, 1991.

Frederiske, Julie. A Different Kind of War . Gweru, Zimbabwe: Mambo Press, n.d.

Hachten, William A. The World News Prism: Changing Media, Clashing Ideologies . Ames, IA: The Iowa University Press, n.d.

Jeter, Phillip, Kuldip R. Rampal, Vibert C. Cambridge, and Vornelius B. Pratt. International Afro Mass Media . Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Merril, John C., ed. Global Journalism: Survey of International Communication , Second Ed. New York: Long-man, 1991.

Ungar, Sanford J. Africa . Simon & Schuster, 1985.

World Geography Encyclopedia , Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2002.

Tendayi S. Kumbula

This article has been mosy helpful to me.It is well presented and very informative.Well done

Good times !