Tajikistan

Basic Data

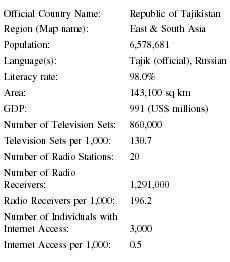

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Tajikistan |

| Region (Map name): | East & South Asia |

| Population: | 6,578,681 |

| Language(s): | Tajik (official), Russian |

| Literacy rate: | 98.0% |

| Area: | 143,100 sq km |

| GDP: | 991 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Sets: | 860,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 130.7 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 20 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 1,291,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 196.2 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 3,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 0.5 |

Background & General Characteristics

Tajikistan borders China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west and Afghanistan on its southern frontier. With a 2001 estimated population of 6,579,000 growing at a 2.1 percent annual rate, 65 percent of its people are ethnic Tajik, about 25 percent are Uzbek, 3.5 percent are Russian, and other groups make up the rest. Russians, who numbered roughly half a million a decade ago, fled the country en masse during the recent civil war. 80 percent of the population is Sunni Muslim, while 5 percent are Shi'a Muslim. Tajik is the official language but Russian is widely used in government and business circles. The long local form of Tajikistan is Jumhurii Tojikiston .

Tajikistan, literally the "land of the Tajiks," has ancient cultural roots. The people now known as the Tajiks are the Persian speakers of Central Asia, some of whose ancestors inhabited Central Asia at the dawn of history. Despite the long heritage of its indigenous peoples, Tajikistan has existed as a state only since the Soviet Union decreed its existence in 1924.

The origin of the name Tajik has been embroiled in twentieth-century political disputes about whether Turkic or Iranian people were the original inhabitants of Central Asia. Until the twentieth century, people in the region used two types of distinction to identify themselves: way of life—either nomadic or sedentary—and place of residence. Most, if not all, of what is today Tajikistan was part of ancient Persia's Achaemenid Empire which was subdued by Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. and then became part of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. The northern part of what is now Tajikistan was part of Soghdiana. As intermediaries on the Silk Route between China and markets to the west and south, the Soghdians imparted religions such as Buddhism, Netorian Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, as well as their own alphabet and other knowledge, to peoples along the trade routes. Islamic Arabs began the conquest of the region in earnest in the early eighth century. In the development of a modern Tajik national identity, the most important state in Central Asia after the Islamic conquest was the Persian-speaking Samanid principality (875-999). During their reign, the Samanids supported the revival of the written Persian language. Samanid literary patronage played an important role in preserving the culture of pre-Islamic Iran.

During the first centuries A.D., Chinese involvement in this region waxed and waned, decreasing sharply after the Islamic conquest but not disappearing completely. As late as the nineteenth century, China attempted to press its claim to the Pamir region of what is now southeastern Tajikistan. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, China occasionally has revived its claim to part of this region. Beginning in the ninth century, Turkish penetration of the Persian cultural sphere increased in Central Asia. The in-flux of even greater numbers of Turkic peoples began in the eleventh century. The Turkic peoples who moved into southern Central Asia, including what later became Tajikistan, were influenced to varying degrees by Persian culture. Over the generations, some converted Turks changed from pastoral nomadism to a sedentary way of life, which brought them into closer contact with the sedentary Persian speakers.

Until 1991, Tajikistan was part of the former USSR. In Soviet times, the investment in social structures allowed Tajikistan to reach a high level of development within the education system. Up until the beginning of the 1990s, literacy among the adult population (99 percent according to the 1989 Soviet census) and well-educated labor force was maintained while 77 percent had a secondary education and above. The educational institutions at all levels were accessible to the majority of the population. Despite being one of the poorest of the former Soviet block nations, it still maintains a high literacy rate of 98 percent. Immediately after the war, the government approved a law that made education a right for all. However, this right is yet to be implemented. Prior to independence, the universal language of instruction was Russian, and literacy almost exclusively meant literacy in Russian. Today, education is at least nominally available in five languages throughout the country: Tajik, Russian, Uzbek, Kyrghyz, and Turkmen. In practice, however, the location of schools offering instruction in a family's preferred language (other than Tajik) may prohibit their children's attendance.

Of the five Central Asian states that declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Tajikistan is the smallest in area and the third largest in population. Land-locked and mountainous, the republic has some valuable natural resources, such as waterpower and minerals, but arable land is scarce, the industrial base is narrow, and the communications and transportation infrastructures are poorly developed. Following independence in 1991, Tajikistan faced a series of crises. Separation from the Soviet Union caused an immediate economic collapse. Non-inclusion in the ruble zone caused a cash crisis that was exacerbated when Russia delayed payments on shipments of cotton because of Tajik debts to Russia. A civil war in 1991-93 resulted in significant loss of life and property and left close to 500,000 people homeless and set back children's education. General damage is estimated at US$7 billion. As of 2000, Tajikistan ranked among the 20 poorest nations of the world. With an average per capita annual income of some US$130, about 85 percent of Tajiks live below the poverty line.

Tajikistan has featured prominently in the recent drive to root out Al Qaeda terrorists and depose the Taliban government in Afghanistan. Despite risks from its own Islamists, the Tajikistan government quickly gave the international forces necessary access for the intervention and its role in the conflict and the supply of humanitarian relief has been essential. Notwithstanding its disadvantages, Tajikistan is successfully, if haltingly, making a transition to normalcy, civil order and democracy. Despite several potentially destabilizing events during 2001, such as the assassination of cabinet officials by unknown assailants, the various parties remain committed to peace even as they struggle for influence within the political landscape. The government continues to work to maintain a balance between various factions, including those from the president's party and former opposition members integrated into the government following the 1997 Peace Accord. The peace process resulted in a unique coalition government (of Islamists and former Communists), and the Islamists are a vocal opposition.

There are no daily newspapers in Tajikistan, although 203 newspapers and 56 magazines are officially registered. Two opposition newspapers started publication again in 1999 following the lifting of a six-year ban on the activities of their parties and movements. With the economy in ruins and much of the population living in poverty, Tajikistan still does not have a viable daily press. The authorities control the presses and publishing, and obtaining a license can take several years. Today, the country relies on small-volume weekly papers, most of them filling news holes with horoscopes and anecdotes from the Russian yellow press. Examples of Tajik newspapers are the following: the Jumhuriyat —government-owned and published in Tajik three times a week; Khalq Ovozi —government-owned and published in Uzbek three times a week; Narodnaya Gazeta —government-owned and published in Russian three times a week; Nido-i Ranjbar —Tajik-language weekly and published by the Communist Party; Golos Tajikistana —Russian-language weekly and published by the Communist Party; Tojikiston —government-owned Tajik-language weekly; and the Najot —weekly and published by the former opposition Islamic Rebirth Party.

The information vacuum in the country can bring about the most undesirable consequences, exerting negative influence on further social and political developments in the region. Ten years after a strong Soviet ideology dissolved, other forces are snatching opportunities to define a new ideology at a crossroad of the European and Asian civilizations. In areas in which the free media cannot operate, and where there is a lack of education, that ideology can grow from fear and violence.

The absence of analytical journalism accounts for the fact that motives for frequent reshuffles in power structures and changes in home and foreign political priorities proclaimed by the country's leadership remain unclear to the broad range of readers, viewers and listeners.

Economic Framework

The economy is a state-controlled system making a difficult transition to a market-based one. Most of the work force (50 percent) is engaged in agriculture (20 percent GDP), part of which remains collectivized. Government revenue depends highly on state-controlled cotton production. The small industrial sector (18 percent GDP) is dominated by aluminum production, another critical source of government revenue, although most Soviet-era factories operate at a minimal level, if at all. Small-scale privatization is over 80 percent complete, but the level of medium to large-scale privatization is much lower (approximately 16 percent) with the heavy industry, wholesale trade, and transport sectors remaining largely under state control. Many, but not all, wages and pensions are paid. The country is poor, with a per capita gross national product of approximately $290, according to World Bank data. While the current growth rate runs at 5.1 percent, inflation is running at 33 percent. Only 28 percent of the population is urban. Tajikistan depends on aid from Russia and Uzbekistan and on international humanitarian assistance for much of its basic subsistence needs. The failure of the Soviet economic system has been accompanied by a rise in narcotics trafficking and other forms of corruption. This development has led to clear disparities of income between the vast majority of the population and a small number of former pro-government and opposition warlords, who control many of the legal and most of the criminal sectors of the economy. World Bank development efforts are focusing on transnational projects for oil and hydroelectric exploitation. With their large reserves of oil and gas, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan are eager to build pipelines and capitalize on potential regional and global markets. The Turkmenistan government broached the possibility of a natural gas pipeline to flow to Afghanistan, Pakistan and India. Water-rich Tajikistan has big hydro potential and could be a source of water for the entire region, yet downstream sharing will be difficult to achieve because of political exigencies and nationalistic tendencies.

Tajikistan is ruled by an authoritarian regime that has established some nominally democratic institutions. President Emomali Rahmonov and an inner circle of fellow natives of the Kulyab region continued to dominate the government; however, Rahmonov's narrow base of support limited his control of the entire territory of the country. Rahmonov won reelection in a November 1999 election that was flawed seriously and was neither free nor fair according to outside observers. As a result of 1997 peace accords that ended the civil war, some former opposition figures continue to hold seats in the government. Rahmonov's supporters overwhelmingly won. Although February parliamentary elections that were neither free nor fair, they were notable for the fact that several opposition parties were allowed to participate, and that one opposition party won two seats in Parliament. Although the Constitution was adopted in 1994 and amended in September 1999, political decision-making normally takes the form of power plays among the various factions, formerly aligned with the other side during the civil war, that now make up the government.

The legacy of civil war continued to affect the government, which still faced the problems of demobilizing and reintegrating former opposition troops and maintaining law and order while rival armed factions competed for power. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, it is not independent in practice. The Ministries of Interior, Security, and Defense share responsibility for internal security, although the government actually relies on a handful of commanders who use their forces almost as private armies. Some regions of the country remained effectively outside the government's control, and government control in other areas existed only by day, or at the sufferance of local former opposition commanders. The soldiers of some of these commanders are involved in crime and corruption. The Russian Army's 201st Motorized Rifle Division, part of a Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) peacekeeping force established in 1993, remained in the country and continued to have a major influence on political developments; however, the division began to transition into a new status on a permanent military base after the peacekeeping mandate ended in September.

The number of independent and local newspapers is increasing, but only a handful of them attempt to cover serious news. Several are organs of political parties or blocs. The government exerted pressure on newspapers critical of it. Najot, the new official paper of the Islamic Renaissance Party, which began weekly publication in October 1999, continued to publish during the year. It experienced indirect government censorship in the early summer, apparently in retaliation for publishing a serialized translation of a foreign human rights report critical of the government. It temporarily lost its access to state-run printing presses and has been forced to rely on a small, privately owned printing press to publish its editions.

Civil war along with regional clan lines, political violence and state repression has made Tajikistan one of the most dangerous places for journalists. Peace accord between government and United Tajik Opposition (UTO) has never worked out. Absolute anarchy is prevailing in the ranks of both UTO and government troops. Civilian deaths, hostage taking, looting and torching of houses, rape and summary executions have occurred—the country has seen the worse human rights abuses since the height of the 1992-97 war. Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases of extortion, kidnapping, and beating of ordinary civilians by Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Defense, and Ministry of Emergency situations personnel. Issues high on the agenda in Tajikistan included how to advance progress in the social sectors and the need to push ahead in tackling corruption and governance issues.

The most recent Country Assistance Strategy (CAS)—the central vehicle for Board of Directors' review of the World Bank Group's assistance strategy for Tajikistan—focuses on four main areas: privatization (the first Structural Adjustment Credit); farm restructuring and improved agricultural support services (the Farm Privatization Project, the Rural Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project); social services (the Education Learning and Innovation Loan, the Primary Health Care Reform Project); and strengthened institutional capacity for reform implementation at the sector level (the Second Institution Building Technical Assistance Project). USAID's program to strengthen democratic culture among citizens and targeted institutions seeks to create stronger and more sustainable civic and advocacy organizations; increase the availability of information on civic rights and domestic public issues; and increase opportunities for citizen participation in governance. Despite the difficult travel situation to and within Tajikistan (and the security situation which demands restricted travel), support to Tajikistan's NGOs led to a marked improvement in NGO advocacy, service provision, and organizational capacity.

At the time of independence, Tajikistan had several long-established official newspapers that had been supported by the communist regime. These included newspapers circulated throughout the republic in Tajik, Russian, and Uzbek, as well as papers on the provincial, district, and city levels. Beginning in 1991, changes in newspapers' names reflected political changes in the republic. For example, the Tajik republican newspaper, long known as Tojikistoni Soveti (Soviet Tajikistan), became first Tojikistoni Shuravi (using the Persian word for "council" or "soviet") and then Jumhuriyat (Republic). The equivalent Russian-language newspaper went from Kommunist Tadzhikistana (Tajikistan Communist) to Narodnaya Gazeta (People's Newspaper). Under the changing political conditions of the late-Soviet and early independence periods, new newspapers appeared, representing such groups as the journalists' union, the Persian-Tajik Language Foundation, cultural and religious groups, and opposition political parties. After antireformists returned to power at the end of 1992, however, the victors cracked down on the press.

In the Soviet era, Tajikistan's magazines included publications specializing in health, educational, rural, and women's issues, as well as communist party affairs. Several were intended especially for children. Literary magazines were published in both Russian and Tajik. The Academy of Sciences of Tajikistan published five scholarly journals. In the post-independence years, however, Tajikistan's poverty forced discontinuation of such items. In the early 1990s, Tajikistan had three main publishing houses. After the civil war, the combination of political repression and acute economic problems disrupted many publication activities. In this period, all of the country's major newspapers were funded fully or in part by the government, and their news coverage followed only the government's line. The only news agency, Khovar, was a government bureau. Tajikistan drew international criticism for the reported killing and jailing of journalists. Government officials often make it clear to journalists what news should not be covered, and reporters practice consideration self-censorship.

There are about 200 periodicals published in Tajikistan. Fifty of them are either independent or partly affiliated. Two new private newspapers began publishing in 1998. One is affiliated with the UTO's fighters; the other with UTO members of the National Reconciliation Commission. Like most newspapers, both have small circulations. Most private media, however, are not financially viable. Because of low advertising revenues and circulation bases, few papers publish daily. Biznis i Politica, a paper subsidized by a private commodities exchange firm, is one of a few successful papers.

State TV and radio are financed from the national budget; revenues from advertising do not allow for financial independence. Politically, the government channels are biased and scrutiny of the authorities is entirely absent. According to sources, there are no independent broadcasters in Tajikistan. However, Internews (the only foreign media assistance organization with an office in Tajikistan) reports that two private TV channels are currently operative.

Foreign radio stations broadcasting in Russian and Tajik are the BBC, Voice of America, Radio Liberty and Voice of Free Tajikistan. The latter is in fact the United Tajik Opposition radio station (funded by Iran), broadcasting from Kunduz Province in northern Afghanistan. Combined with the opposition papers smuggled into the republic, such as Charoghi Rooz (Moscow) and Paiki Piruzi (Iran), they provide information to a selected part of the information-hungry population.

Salaries for journalists are poor and do normally not exceed the national average. In some cases (independent outlets), earnings may be higher, yet not above $20 per month. Due to the economic chaos, payment is occasionally delayed for months. Combined with the dangers and lack of freedom, few young people are motivated to enter the profession.

There are no professional organizations defending the rights of journalists, monitoring violations or trying to improve working conditions. The Journalists' Union, headed by Mirzokhaet Davlatov, formally represents the interests of journalists, yet in practice is not able to provide substantive support or assistance.

In 1995, 24 new publications were registered and in 1996 the total number of registered newspapers amounted to 213. Of these, 24 newspapers are supposedly distributed throughout the republic. However, most of these outlets either appear irregularly or folded. The bulk of the newspapers (over 70 percent) are either official central, regional, city or district papers, or owned by various ministries and state committees.

The total circulation of newspapers plummeted eight-fold after January 1991 (when the combined print-run stood at two million). In 2002, the circulation of newspapers rarely exceeded 5,000 copies.

Although the state-controlled press is due to receive subsidies, some papers (such as the Russian-language Narodnaya Gazeta or the Tajik-language Dzhumhurriyat (Republic) and Paemi Dushanbe (Evening Dushanbe)) appear irregularly since financial assistance was lowered or virtually ceased. Consequently, several of these papers will most likely fold in the foreseeable future. Other 'official' papers (such as Sadoi Mardum (People's Voice)) continue to receive support from the government. The most important governmental state-supported papers are:

- Sadoi Mardum , started in 1991, is printed in the Tajik language, and has a circulation of 5,000. It is published by the Tajik parliament and appears twice a week. Sadoi Mardum publishes predominantly parliamentary documents and pro-governmental articles on political issues. It is distributed nationwide, printed by the Sharqi Ozod publishing house, has a staff of 40 journalists and cooperates with the agency Khovar.

- Dzhumhurriyat , established in 1925, is a Tajik-language paper with a circulation around 10,000. It is published by the government and appears twice a week. Dzhumhurriyat prints official documents and information from various Ministries, as well as pro-governmental articles. It is printed by the Sharqi Ozod publishing house, has a staff of 35 journalists and cooperates with the agency Khovar.

- Narodnaya Gazeta , established in 1925, is Russian-language and published as a joint edition of the parliament and the government. The circulation totals 2,500 and the paper is supposed to appear twice a week, yet is published with long intervals (in 1996, six issues were published). Besides official documents, Narodnaya Gazeta reprints articles from Russian pro-communist newspapers, and is distributed in Dushanbe, the Leninski district, and partially in the Leninabad region.

- Khalk Ovozi has existed since 1929, is Uzbek-language, is printed by the parliament, and has a print-run of around 7,000 copies. It appears weekly, has a staff of 56, is printed at Sharqi Ozod (four pages) and also cooperates with Khovar.

Nominally independent newspapers are financed by sponsors, political associations or commercial groups. Generally, these backers determine the editorial policy and content of the publication. However, newspapers do not disclose information regarding their financial sources.

The most independent newspaper (as far as possible under the current circumstances) is Vecherniye Novosti (Evening News). It was essentially established in 1968 under the name Vecherni Dushanbe , yet was renamed in 1996. The paper is owned by the editorial staff, and prints articles on city life and political issues, aimed at the intelligentsia. Vecherniye Novosti battles for survival by selling issues on the street and trying to find sponsors without strings attached. The weekly is said to be distributed nation-wide, with a total print-run of 10,000. The paper has a staff of 15 journalists.

Biznes i politika (Business and Politics) started in 1992 and is a Russian-language weekly with a circulation of 15,000, distributed nation-wide. It is also formally independent and financed by commercial groups. The newspaper contains a variety of information on political and economic issues, reprints material from Russian editions, has columns on sports, culture, etc. It has a staff of 40 journalists.

Both Biznes i politika and Vecherniye Novosti sup-port the government. They are issued weekly, whilst both were daily papers up to 1999. The reasons illustrate the structural difficulties for print media. There is a shortage of printing material (films, ink) and paper. High costs, combined with the extremely low purchasing power of the population ensured insignificant print-runs. Moreover, the "national" editions do not reach the rural areas, which further limits their circulation.

The newspaper Charkhi Gardun was established in 1996. It is a private information-cultural newspaper in Tajik with a circulation of around 6,000, distributed in the south of the country. Chas Iks has existed since May 1995 and highlights the activity of the Socio-Ecological Union of Tajikistan. It has a circulation of 2,000 and is privately-owned.

The lack of private local broadcasters, combined with the disrupted distribution of "national" newspapers in the regions, makes the state TV and radio the most important source of news outside Dushanbe. Generally, the regions can receive the national TV channel, a local state-owned broadcaster and Russian ORT and RTR. Russian channels are transmitted by satellite.

One TV channel, Timur Malik, operates in the region of Leninabad. Prior to 1992, cable TV stations existed, yet they were banned. The official explanation concerned alleged "pornographic movies and other inadmissible programmes." It is, however, generally accepted that the political advertising carried by the cable TV station prior to the elections caused their prohibition. Although data are not available, it appears that governmental papers are in low demand, if available. Advertising issues appear more popular.

Press Laws

Both the 1991 Law on Press Freedom and the 1994 constitution guarantee freedom of the press. Under the constitution of the Republic of Tajikistan all forms of censorship are outlawed. It also guaranteed citizens access to the media, but practice is far from the words on the text of these documents. Government and armed groups routinely ignore these rights. Instead they use the same bill to limit the freedom of the press in the Republic. For example the provision on libel of the 1991 Law on Press Freedom enables government officials to punish critical viewpoints for "irresponsible journalism" which includes jail terms and fines.

Legal rights for both broadcasters and individual journalists in Tajikistan remain tenuous. Journalists, broadcasters, and individual citizens who disagree with government policies are discouraged from speaking freely or critically. The government exercises control over the media both overtly through legislation and indirectly through such mechanisms as "friendly advice" to reporters on what news should not be covered. The government also controls the printing presses and the supply of news-print and broadcasting facilities and subsidizes virtually all publications and productions. Editors and journalists fearful of reprisals carefully exercise self-censorship.

Internews Tajikistan maintains a staff lawyer who tracks changes in legislation and practice in all aspects of media law. Internet advocacy issues currently rank high on their agenda and their lawyer also provides consultation to stations on registration, licensing, libel, freedom of information, and other issues related to the media's ability to function freely. Tajikistan ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in 1998. Article 19 of the Covenant states: "Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference; Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice." The Constitution of Tajikistan upholds freedom of expression and bans censorship: "Every person is guaranteed freedom of speech, publishing, and the right to use means of mass information. State censorship and prosecution for criticism is prohibited. The list of information constituting a state secret is specified by law."

State censorship is forbidden by Tajikistan's obligations under international and domestic law, covenants it has ratified and the nation's Constitution. Although censorship is not a systematic practice, in reality pre-publication censorship occurs. Generally, journalists choose not to use the courts to defend themselves and stay away from issues sensitive to the authorities. Self-censorship prevents large-scale pre-publication censorship from occurring, while those incidents that do occur most often go unreported. The government of Tajikistan maintains that certain restrictions on freedom of expression are necessary to protect development, security, and other interests. Many state officials, and even Tajik journalists, hold the view that unrestricted freedom of expression in part spurred the civil war in 1992. They agree that coverage of sensitive topics, such as the negative consequences of the war, must necessarily be limited to preserve national security interests and stability. Although this view is not strictly state policy, little serious discussion of the negative impacts of the civil war appears in the press, because of curbs on the media, censorship and an uncontrolled culture of violence and impunity.

The Committee to Protect Journalism (CPJ) also raised concerns about the Tajikistan Penal Code, which makes it a crime to publicly defame or insult a person's honor or reputation. In addition, Article 137 stipulates that publicly insulting Tajik President Rakhmonov is punishable by up to five years in jail.

Censorship

Journalists working in Tajikistan, one of five Central Asian republics that gained independence when the Soviet Union collapsed, enjoy a very limited version of press freedom. Certain topics are taboo, particularly criticism of President Imomali Rakhmonov and the ruling party. As a result, journalists censor themselves to avoid confrontations with authorities. Indeed, many restrictive measures remain in place since the 1998 decision by the government to extend its power over the media by amending the media law. The amendments gave the official broadcasting committee the right to control the content of any program or material either before or after its production.

The government severely restricts freedom of expression. The sole publishing house for publishing newspapers is owned by the state and denies access to government critics. The government monitors and "counsels" all news media, enforces pre-publication censorship, and imposes burdensome licensing procedures. Electronic media is either state-owned or is dominated by the state.

Direct censorship, such as the systematic vetting by a censorship office of all articles prior to publication, is not standard practice in Tajikistan. Nonetheless, authorities do on occasion prevent certain material or publications from being printed. More often than not, journalists receive a warning in the form of a telephone call from a governmental ministry, offering "guidance"; or printers receive instructions from authorities not to print the publication or article in question.

Journalists frequently are subject to harassment, intimidation, and violence. Sometimes the perpetrators are government authorities, as in the case of a reporter for the state-owned newspaper Jumhuriyat , who was beaten severely by militiamen in August, according to the Center for Journalism in Extreme Situations. In other cases, the perpetrators are criminal or terrorist elements who are believed to have narcotics trafficking connections, as in the cases of Ministry of Interior press center chief Jumankhon Hotami, who was shot and killed near Dushanbe in 1999, and Sergei Sitkovskii, a Russian national working for the newspaper Tojikiston , who was killed in a hit-and-run car accident in 1999. Both were investigating narcotics trafficking at the time of their deaths. There were no developments in their cases by year's end.

State-Press Relations

The authorities threaten or harass journalists and editors who publish views directly critical of President Rakhmonov or of certain government policies. A dramatic example was the July 2001 arrest in Moscow of Dodojon Atovullo, exiled editor-in-chief of the independent opposition newspaper, Charogi Ruz (Light of Day). Atovullo has in recent years published articles accusing Tajik authorities of corruption and involvement in narcotics trafficking activities. Threatened with extradition to Tajikistan to face charges of sedition and publicly slandering the president, he was released in six days after pressure from other governments and international organizations. CPJ also cited the case of reporter Khrushed Atovulloev, from the newspaper Dzhavononi Tojikiston, who was questioned and threatened in June 2001 by officials from the State Security Ministry. CPJ said the heavy-handed treatment was in retaliation for an article describing abysmal living conditions endured by university students and bribe-taking by teaching staff. CPJ said these incidents are all in violation of Article 162 of the Tajikistan Penal Code, which makes it illegal to obstruct a journalist's professional activities.

The government's human rights record remains poor and the government continues to commit serious abuses. The February parliamentary elections represented an improvement in the citizens' right to change their government; however, this right remains restricted. Some members of the security forces committed extrajudicial killings. There were a number of disappearances. Security forces frequently tortured, beat, and abused detainees. These forces also were responsible for threats, extortion, looting, and abuse of civilians. Certain battalions of nominally government forces operated quasi-independently under their leaders. Impunity remains a problem, and the government prosecuted few of the persons who committed these abuses. Prison conditions remained harsh and life threatening. The government continued to use arbitrary arrest and detention and also arrested persons for political reasons. Lengthy pretrial detention remains a problem. Basic problems of rule of law persist. There are often long delays before trials, and the judiciary is subject to political and paramilitary pressure.

The government has continued to severely restrict freedom of speech and the press. The government severely limited opposition access to state-run radio and television; however, an opposition newspaper begun in 1998 continued to publish, and a number of small television stations were operated by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Journalists practice self-censorship. The government restricts freedom of assembly and association by exercising strict control over political organizations; it banned three opposition parties and prevented another from being registered. A number of parliamentary candidates were prevented from registering for the elections. There are some restrictions on freedom of religion and on freedom of movement. The government still has not established a human rights ombudsman position, despite a 1996 pledge to do so.

Some members of the government security forces and government-aligned militias committed serious human rights abuses. Journalists regularly risked beatings at the hand of law enforcement authorities (or at least armed individuals dressed as and claiming to be law enforcement authorities). For example, the Center for Journalism in Extreme Situations reported that militiamen seized a reporter for the state-owned newspaper Jumhuriyat in Dushanbe in August, forced him into a car, beat him en route to a militia station, where they beat him so badly that he suffered a concussion and hearing loss in one ear.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

The current Tajikistan government does not welcome the presence of foreign journalists or the information incoming from foreign sources. Official investigations into the murders of journalists have given almost no results. Human Rights Watch report how Khorog-based state radio employee Umed Mamadponoev was detained by police in May and "disappeared" after producing a locally aired program on the army mistreatment of soldiers from Gorno-Badakhshan.

Some papers are supported by the Islamic Republic of Iran (e.g. Somon , the newspaper of the Tajik Language Foundation, and the magazine Dare). These publications do, however, focus exclusively on scientific or cultural issues and are not involved in politics.

The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) sent a letter on May 14, 2002, to the Tajikistan government outlining its concerns about the lack of press freedom in the country. The press watchdog said that government harassment, intimidation, and censorship regularly stifle press freedoms in Tajikistan. CPJ's program coordinator for Europe and Central Asia, Alex Lupis, said that one of the most important points CPJ wants the Tajik authorities to address is the ongoing intimidation and attack of journalists by government officials. The CPJ has documented eight such cases since 1992. In 1998 and 1999, journalists continued to receive death threats, and the UTO and other armed groups took journalists hostage on several occasions. The government continued to arrest journalists based in the Leninabad region, deny Leninabadi newspapers permission to use government run printing houses and otherwise restrict the coverage of the Leninabadi-based National Revival Movement and sensitive events in the region.

News Agencies

News agencies that currently exist in Tajikistan are the government-run Khovar news agency and two private agencies, Asia-Plus, which maintains an extensive presence in the Internet, and the Mizon news agency.

Broadcast Media

Television broadcasts first reached Tajikistan in 1959 from Uzbekistan. Subsequently, Tajikistan established its own broadcasting facilities in Dushanbe, under the direction of the government's Tajikistan Television Administration. Color broadcasts use the European SECAM system. Television programming is relayed from stations in Iran, Russia, and Turkey. In mountainous villages, television viewing is restricted by limited electrical supply and retransmission facilities. In February 1994, President Imomali Rakhmonov took direct control of broadcasting services under the guise of ensuring objectivity. Throughout the years, government dominance has not diminished. The state run Tajik Radio is the major radio service, while the only national television service is the state run Tajik Television. The UTO also operates a radio station. In 1992, 854,000 radios and 860,000 televisions were in use. There are two independent radio stations, one in the north and the other in the south. Eighteen non-governmental television stations have opened in Tajikistan since the USAID-backed Internews started there in 1995.

Laws governing the media in Tajikistan protect media freedoms. These include the Law on the Press and Other Mass Media, adopted by the Supreme Soviet of the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic on December 14, 1990, and the Law on Television and Radio Broadcasting, adopted on December 14, 1996. Under the terms of the 1997 General Agreement, amendments are to be made to current media legislation to bring it into greater conformity with international protections, although after five years there were no signs that such steps had been initiated.

Television and radio broadcasting is the monopoly of the State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company of Tajikistan, which is controlled by the Ministry of Communications. In 1995 the radio broadcasting system included thirteen AM stations and three FM stations. Several frequencies offer relayed programming from Iran, Russia, and Turkey. Although radio broadcasting is primarily in Tajik, Russian and Uzbek programming also is offered. In 1988 broadcasting began in German, Kyrgyz, and Crimean Tatar as well. In February 1994, the state broadcasting company came under the direct control of head of state Imomali Rahmonov.

There is one government-run television network; its several local stations cover regional and local issues from an official point of view. There are 11 independent television stations, although two have suspended operations due to financial problems. Some of these stations have independent broadcast facilities, but most have to rely on the state studios. According to the U.S. Department of State, the process of obtaining a license for an independent television station is time consuming and requires the payment of high fees and costly bribes. However, authorities have not prevented any station from getting a license. Radio liberty and two other Russian television channels are also available in Tajikistan. There are 36 nongovernmental television stations, not all of which are operating at any one time and only a handful of which can be considered genuinely independent. The Islamic Renaissance Party was able to begin broadcasting a weekly television program on one such station. Some have independent studio facilities. These stations continued to experience administrative and legal harassment. To obtain licenses, independent television stations must work through two government agencies, the Ministry of Communications, and the State Committee on Radio and Television. At every stage of the bureaucratic process, there are high official and unofficial fees.

The government continued to prevent independent radio stations from operating by interminably delaying applications for broadcasting licenses. At least two independent radio stations in Dushanbe have had their license applications pending without explanation since the summer of 1998.

Electronic News Media

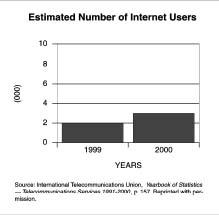

In 1994 Tajikistan's telephone system remained quite limited. It included 259,600 main lines, an average of one line per twenty-two people—the lowest ratio among former Soviet republics. U.S. based Central Asian Development Agency first introduced the Internet in Tajikistan in 1995. Internet is available mainly in public communication places. While the number of people who use the Internet is questionable, as of 1998 only about 1,500 people in Tajikistan had an e-mail address.

An on-line service, Internews Tajikistan produces a weekly news magazine, Nabzeh Zendaghi (The Pulse of Life), which features news stories from fifteen independent stations broadcasting in ten cities, as well as free-lance corespondents in other cities without nongovernmental TV. The program brings news from around the country, including regions isolated, by geography and social barriers, to upwards to one million viewers.

Access to the Internet is limited partly by state control. The government allowed a handful of Internet provider companies to begin operating during the year, but high fees and limited capacity put access to information over the Internet out of reach for most citizens and essentially controls the electronic media.

Education & Training

Academic expression is limited principally by the complete reliance of scientific institutes upon government funding, and in practical terms by the need to find supplementary employment to generate sufficient income, leaving little time for academic writing.

The need for more professional journalism has been highlighted by the recent events in Afghanistan and the lack of Tajikistan presence in international news releases. "I see two reasons for this," states the prominent Armenian journalist Mark Grigoryan, who is familiar with the Tajikistan press. "The first one is of purely professional nature. I am afraid that many of my colleagues are not sufficiently professional to be able to analyze the situation. For analyzing a situation implies a hunt for hard-toget evidence, including finding and assessing facts, and having the ability to get outside of realities and facts. Certainly, it is easier to wait for the Russian newspapers to publish material and then copy it. Certainly too, it is much easier to collect material that is just at hand."

Last May, the Asia-Plus News Agency launched an UNICEF project to train would-be journalists. School-children from the Tajik capital passed a thorough screening to receive basic training in journalism. Theory was followed by practical assignments: to write a news item or article, or to conduct an interview. Ms. Natalya Bruker, an assistant professor from the Russo-Tajik Slavonic

Summary

Tajikistan remains the least stable country in Central Asia as the post-war period has been marred by frequent outbreaks of violence. Recently, Tajikistan has been accused by its neighbors of tolerating the presence of training camps for Islamic rebels on its territory, an accusation that it has strongly denied. Owing to the continuing security problems and dire economic situation, Tajikistan relies heavily on Russian assistance. It is the only country in the region that allows a Russian military presence, charged in particular with guarding its border with Afghanistan. Skirmishes between the Russian military and drug smugglers crossing illegally from Afghanistan occur regularly, as Tajikistan is the first stop on the drug route to Russia and the West. As a result, the exercise of investigative reporting in Tajikistan remains extremely hazardous, making it one of the most dangerous areas in the world to report on and carry out normal press and media activities.

Bibliography

Akin, Muriel. The Subtlest Battle: Islam in Soviet Tajiki-stan . Philadelphia: Foreign Policy Research Institute, 1989.

——. "The Survival of Islam in Soviet Tajikistan." Middle East Journal, 43, No. 4 (Autumn, 1989): 605-18.

——. "Tajikistan: Ancient Heritage, New Politics." In Nation and Politics in the Soviet Successor States , eds. Ian Bremmer and Ray Taras, 361-83. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Akiner, Shirin. Islamic Peoples of the Soviet Union: An Historical and Statistical Handbook. New York: Kegan Paul International, 1986.

Akiner, Shirin, ed. Economic and Political Trends in Central Asia. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1992.

Allworth, Edward, ed. Muslim Communities Reemerge: Historical Perspectives. Durham: Duke University Press, 1994.

Amnesty International. "Tadzhikistan." London, 1993.

Andreyev, M.S. "Po etnografii tadzhikov: Nekotoryye svedeniya." In Tadzhikistan. Tashkent: Obshchestvo dlya izucheniya Tadzhikistana i iranskikh narodnostey za yego predelami, 151-77. 1925.

Banuazizi, Ali, and Myron Weiner, eds. The New Geo-politics of Central Asia and Its Borderlands. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994.

Blank, Stephen. "Energy, Economics and Security in Central Asia: Russia and Its Rivals." Central Asian Survey, 14, No. 3 (1995): 373-406.

Carrere d'Encausse, Helene. Reforme et Revolution chez les Musulmans de l'Empire russe. Paris: Librarie Armand Colin, 1966.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Handbook of International Economic Statistics 1995. Washington: GPO, 1995.

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). "Tajikistan." The World Factbook. Available from http://www.cia.gov .

Dawisha, Karen, and Bruce Parrott. Russia and the New States of Eurasia: The Politics of Upheaval. Port Chester. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Entsiklopediyai sovetii Tojik. Dushanbe: Sarredaktsiyai ilmii entsiklopediyai sovetii Tojik, 1978-1987.

Europa World Year Book 1996. London: Europa, 1996.

Fedorova, T.I. Goroda Tadzhikistana i problemy rosta i razvitiya . Dushanbe: Irfon, 1981.

Ferdinand, Peter. The New States of Central Asia and Their Neighbors. New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1994.

Forsythe, Rosemarie. "The Politics of Oil in the Caucasus and Central Asia," Adelphi Papers, 300, May 1996.

Freedom House. "Tajikistan: Nations in Transit 1998." Available from www.freedomhouse.org .

——. "Civil War in Tajikistan and Its International Repercussions." Critique (Spring 1995): 3-24.

——. Gretsky, Sergei. "Russia and Tajikistan." In Regional Power Rivalries in the New Eurasia: Russia, Turkey and Iran, eds. A.Z. Rubinstein and O.M. Smolansky, 231-51. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1995.

The History of Cultural Construction in Tajikistan, 1917-1977, 2. Dushanbe: Donish, 1983.

Human Rights Watch, World Report 1999. Available from http://www.hrw.org/hrw/worldreport99 .

Human Rights Watch, World Report 2000. Available from http://www.hrw.org/hrw/wr2k1/europe/tajikistan. html .

IJNet.Country Profile: Tajikistan. Available from http:// www.ijnet.org/Profile/CEENIS/Tajikistan/media.html .

Internews. "Media in the CIS." Available from www.internews.ru/books/media/tajikistan_4.html .

Mandelbaum, Michael, ed. Central Asia and the World: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan. New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1994.

Migranyan, Andranik. "Russia and the Near Abroad," Current Digest of the Post-Soviet Press, 47 (March 1994): 6-11.

Naumkin, Vitaly. State, Religion and Society in Central Asia: A Post-Soviet Critique. London: Ithaca Press, 1993.

Olcott, Martha Brill. Central Asia's New States: Independence, Foreign Policy and Regional Security. Washington: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996.

PlanEcon. Review and Outlook for the Former Soviet Republics. Washington, 1995.

Rakhimov, Rashed. Tajikistan Human Development Report. United Nations Development Program, 1999.

Undeland, Charles, and Nicholas Platt. The Central Asian Republics: Fragments of Empire, Magnets of Wealth. New York: Asia Society, 1994.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Information and Policy Analysis. Demographic Yearbook 1993. New York, 1995.

United Nations Development Program. "Today's technological transformations—creating the network age." Available from www.undp.org/hdr2001/chaptertwo.pdf .

U.S. Department of State. "Background Notes: Tajiki-stan" www.state.gov/www/background_notes .

U.S. Department of State. "1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices." Available from www.state.gov/www/global/human_rights/ 1999_hrp_report/tajikistan.htm .

Virginia Davis Nordin