Thailand

Basic Data

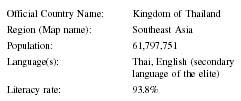

| Official Country Name: | Kingdom of Thailand |

| Region (Map name): | Southeast Asia |

| Population: | 61,797,751 |

| Language(s): | Thai, English (secondary language of the elite) |

| Literacy rate: | 93.8% |

| Area: | 514,000 sq km |

| GDP: | 122,166 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 34 |

| Total Circulation: | 11,753,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 253 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 176 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 18,212 (Baht millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 32.10 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 5 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 15,190,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 245.8 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 151,750 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 2.5 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 231,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 3.7 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 13,960,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 225.9 |

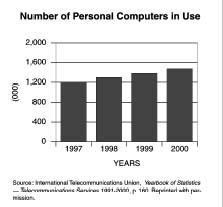

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 1,471,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 23.8 |

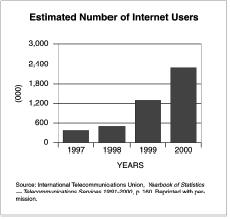

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,300,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 37.2 |

Background & General Characteristics

Thailand, known as Siam until 1932, traces its history back to the thirteenth century to the kingdom of Sukhothai (1257-1378) whose greatest ruler Ramakhamhaeng (1277-1317) united many of the Thai tribes by force of arms, established diplomatic relations with China, and created the Thai alphabet. A series of weak successors and unrest among the vassal states led to the kingdom's surrender (1378) to the more powerful neighboring state of Aytthaya ruled by King U Thong. Thailand became a federated state under the absolute monarch of U Thong, or Ramathibodi. The Thai people were governed according to a legal code based on Hindu legal texts and Thai customs but accepting Theravada Buddhism as the Thai people's official religion. During the Ayutthaya Period (1350-1767), Thailand's kings came under the influence of the neighboring Khmers (Cambodians). Thai kings remained paternalistic and absolutist rulers, but they adopted the Khmer interpretation of king-ship, which witnessed their withdrawal from society behind a wall of taboos and rituals and the assumption of divinity as the incarnated Shiva.

Thailand's Chakkri Dynasty came to power in 1782 when General Chakkri (1782-1809) replaced the executed last ruler of the Ayutthaya kingdom. As King Yot Fa, or Rama I, General Chakkri moved the capital to Bang-kok, revived the economy, preserved the artistic culture of the Thai, and maintained the nation's independence against growing incursions by Cambodia, Burma, and Great Britain. Nineteenth-century monarch King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) was the first Thai ruler educated by western tutors. Chulalongkorn instituted a number of western-style reforms, which included a modern judiciary, the reform of state finances, and the adoption of modern accounting methods. Chulalongkorn ended the ritual of prostration, abolished slavery, created a standing army, and decentralized the bureaucracy by dividing it into departments and local administrative units.

King Chulalongkorn's western-oriented reforms maintained Thai independence against both British and French attempts at imperialistic conquest, making Thailand the only nation in Southeast Asia to escape colonization but at the cost of some Thai territory surrendered to both French Indochina and British India. The themes of modernization and westernization continued under Kings Rama VI and Rama VII. However, in 1932, civil servants and army officers, who were opposed to the actions of the government but not the King, engineered a bloodless takeover of the Thai state. Since the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in 1932, Thailand has witnessed 17 military coups, 53 governments, and 16 constitutions. Throughout these political changes, the position of the Thai King remains revered and respected. The King is accepted as the moral voice of the nation.

Missionaries wanting to influence the King started Thailand's first newspaper in 1844. The role of the print media and freedom of the press in Thailand has historically been affected by the particular monarch in power and after 1932, by the coup leaders and the politicians who assumed governing control. Newspapers sometimes enjoyed more freedom to print under absolute rulers than they were allowed during constitutional regimes. Since 1932 newspapers have been traditionally linked to a political party, and their ability to publish depended on the attitude of the current prime minister who was likely to be a prominent member of the Thai military. During the 1950s and 1960s, Thailand's press was poorly paid, ill-regarded, and lacked professional credentials. Many of the newspapers suffered from small circulations and simply served as the personal propaganda instruments of politicians, policemen, or soldiers. Their circulations popularity derived from stories about sex, crime, and mudslinging. The Thai military increasingly regarded the print media's use of sensational headlines to capture reader interest as immoral. Only two Bangkok dailies, Siam Rath and Siam Nikorn , were regarded as legitimate print media offering critical and balanced coverage. Both newspapers influenced the policies of the nation's leaders.

Faced with increasing threats of communist incursions, a military coup took place in 1951. The constitution was suspended. King Bhumibol returned from the United States where he was completing his academic studies. By 1955 the military government felt secure enough to endorse "limited democracy" and allow the people to criticize the regime. The press responded with severe outspoken criticism and verbal attacks on the government. When elections failed to create stable parliamentary governments, the country's experiment with democracy ended in 1958. The government outlawed political parties, jailed critics including students, teachers, labor leaders, journalists, and liberal parliamentarians. A least a dozen newspapers were closed. Work began on yet another constitution.

Under Prime Minister Sarit Thanarat (1959-1963) the government issued the law Announcement No. 17, which required the licensing of all newspaper publishers. Newspapers displeasing to the government were given warnings, impounded, or destroyed. Frightened, many of the nation's best writers abandoned their careers. A new constitution was drafted, and Prime Minister Sarit relaxed some of the more stringent controls on the press in an attempt to create the appearance of a more liberal political climate.

The increasing political instability in the nations bordering Thailand and deeper involvement by the United States in Vietnam prevented constitutional parliamentary government, or were at the least given as the reasons by military-backed governments for the failure to implement a new constitution. From 1963 to 1973, press restrictions were first strictly enforced and then gradually reduced under Prime Minister Thanom Kittikachorn. New technology generated more newspapers competing for circulation by again running highly sensational news stories. Strict self-censorship was found necessary and imposed by the government. In 1971, press restrictions again were reduced, and the government promised to approve Announcement No. 2, which would abolish censorship except for newspapers whose commentary divided the nation.

From 1973 to 1976, the Thai press witnessed its freest period for publication. The new prime minister, Sanya Dharmasakti, was a university professor and popular with journalists. The ban was lifted on new newspapers, and a new constitution offered press freedoms, abolished censorship, and restricted press ownership to Thai citizens. Although Announcement No. 17 remained in effect, it was seldom enforced. Newspapers flourished during this brief period, and licensed newspapers and magazines numbered 853, but only an estimated 10 percent ever went to active publication. The emergence of hundreds of new publications combined with the lifting of press restrictions created a series of new tensions between the press and the government. Although the circulations of many newspapers were very small, their antigovernment positions voiced the views of many new small political parties. Some of these newspapers were nothing more than rumor-mill tabloids using extortion and blackmail to gain financing. Even government officials found themselves subjected to false blackmail threats from a segment of the press, which was both vocal and irresponsible in reporting information.

Under Prime Minister M. R. Kukrit Pramoj, founder of the newspaper Siam Rath , attempts at responsible journalism were introduced, and a new press law was enacted creating a 17-to 21-member committee to control the press based on ethical considerations. Political tensions within Thailand between political factions of both the right and left, clashes with students, and a too sensation-alist and irresponsible press contributed to the conditions that resulted in a violent and bloody coup in 1976. Strict press censorship was once again imposed. Labor unions came under strict regulation, and an anticommunist drive led to purges within the civil service and the education system. For the next 20 years Thailand lurched between military dictatorships and experiments with limited democracy. The prime ministers were usually former generals even during democratic periods of governance.

Thailand is a hereditary constitutional monarchy. The Constitution of 1997 governs the Thai nation. The King is the head of the armed forces and the upholder of the religion. The monarch is sacred and inviolable— "enthroned in a position of revered worship." His powers come from the Thai people. The King exercises legislative power through the parliament and executive power through the cabinet. The King must be consulted and encouraged, and has the right to warn the government when the state is working against the good of the people. Thailand has a bicameral legislature consisting of a 500-member House of Representatives popularly elected and a Senate whose members, previously appointed by the King, are since 2000 popularly elected without political party affiliation. The Prime Minister must be a member of Parliament and is advised by a cabinet of 14.

Article III of the 1997 Constitution pertains to the Rights and Liberties of the Thai People. Sections 26 through state:

In exercising powers of all Courts authorities regard shall be had to human dignity, rights and liberties in accordance with the provisions of the constitution. Rights and liberties recognized by this constitution expressly, by implication or by decisions of the Constitutional Court shall be protected and directly binding on the National Assembly, the Council of Ministers, Courts and other Courts organs in enacting, applying and interpreting laws (Section 27). A person can invoke human dignity or exercise his or her rights and liberties in so far as it is not in violation of rights and liberties of other persons or contrary to this constitution or good morals. A person whose rights and liberties recognized by this constitution are violated can invoke the provisions of this constitution to bring a lawsuit or to defend himself or herself in the court (Section 28). The restriction of such rights and liberties as recognized by the constitution shall not be imposed on a person except by virtue of provisions of the law specifically enacted for the purpose determined by this constitution and only to the extent of necessity and provided that it shall not affect the essential substances of such rights and liberties. (Section 29)

Section 37 guarantees:

A person shall enjoy the liberty of communication by lawful means. The censorship, detention or disclosure of communication between persons including any other act disclosing a statement in the communication between persons shall not be made except by virtue of the provisions of the law specifically enacted for security of the Courts or maintaining public or good morals.

Section 39 extends to each Thai the liberty to:

… express his or her opinion, make speeches, write, print, publicize (sic), and make expression by other means. The restriction on liberty … shall not be imposed except by virtue of the provisions of the law specifically enacted for the purpose of maintaining the security of the Courts, safeguarding the rights, liberties, dignity, reputation, family or privacy rights of other person, maintaining public order or good morals or preventing the deterioration of the mind or health of the public. The closure of a pressing house or a radio or television station in deprivation of the liberty under this section shall not be made. The censorship by a competent official or news or articles before their publication in a newspaper, printed matter or radio or television broadcasting shall not be made except during the time when the country is in a state of war or armed conflict; provided that it must be made by virtue of the law enacted under the provisions (in Article II). The owner of a newspaper or other mass media business shall be a Thai national as provided by law. No grant of money or other properties shall be made by the Courts as subsidies to private newspapers or other mass media.

Section 40 of the Thai constitution states:

Transmission frequencies for radio and television broadcasting and radio telecommunications are national communication resources for public interest. There shall be an independent regulatory body having the duty to distribute the frequencies … and supervise radio or television broadcasting and telecommunication businesses as provided by law … regard shall be had to the utmost public benefit at national and local levels in education, culture, Courts, security, and other public interests including fair and free competition.

In Section 41:

Officials or employees in a private sector undertaking newspaper or radio or television broadcasting businesses shall enjoy their liberties to present news and express their opinions under the constitutional restrictions without the mandate of any Courts agency, Courts enterprise, or the owner of such businesses; provided that it is not contrary to their professional ethics. Government officials, officials or employees or a Courts agency or Courts enterprise engaging in the radio or television broadcasting business enjoy the same liberties as those enjoyed by officials or employees. …

Section 58 guarantees:

A person shall have the right to get access to public information in possession of a Courts agency, Courts enterprise or local government organization, unless the disclosure of such information shall affect the security of the Courts, public safety or interests of other persons which shall be protected as provided by law.

Section 59 continues that:

… a person shall have the right to receive information, explanation and reason from a Courts agency, Courts enterprise or local government organization before permission is given for the operation of any project or activity which may affect the quality of the environment, health, and sanitary conditions, the quality of life or any other material interest concerning him or her or a local community and shall have the right to express his or her opinions on such matters in accordance with the public hearing procedure, as provided by law.

In 1996, Thailand had 30 daily newspapers with the 15 largest newspapers in circulation printed in Bangkok. The Thai-language newspapers, with 1995 circulation figures, are the morning and evening Ban Muang , (100,000), the evening Daily Mirror (50,000), the morning Daily News (400,000), the morning and Sunday Matichon (100,000), the morning Siam Post (50,000), the morning and Sunday Siam Rath (80,000), and the morning Thai Rath (800,000). English-language newspapers are all morning papers published in Bangkok. They are the Bangkok Post (60,000), the Business Day (40,000), the Thailand Times (20,000), and The Nation (40,000). Chinese-language newspapers, all morning Bangkok editions, are Sin Sian Yit Pao (40,000), Sirinakorn Daily News (30,000), Tong Hua Yit Pao (40,000), and the Universal Daily News (36,000).

General interest periodicals, all published in Bang-kok, are the weekly Bangkok Weekly (200,000), the biweekly Koo Sang Koo Som (250,000), the fortnightly Kulla Stri (120,000), and the weekly Skul Thai (120,000). Special interest periodicals published in Bangkok include business magazines, the English-language monthly Business in Thailand (10,000) and the Thai-language monthly Dok Bia (30,000). Popular women's magazines are the weeklies Kwan Ruen (160,000) and Praew (40,000) and the fortnightly Dichan (60,000). Manager Magazine (5,000) is a monthly publication.

Three of Thailand's radio stations serve each of the branches of the nation's armed forces: Sor.Tor.Ror (Navy), Tor.Or (Air Force), and Wor.Por.Tor (Army). Thailand's other major radio stations are Radio Thailand, Tor.Tor.Tor., and the Voice of Free Asia. Thailand's Bangkok-based television stations are Army HAS-TV-5, Bangkok Broadcasting TV-7, Bangkok Entertainment-3, Mass Communications Organization of Thailand (MCOT), and TV-Thailand-11.

Economic Framework

From 1985 to 1995, the Kingdom of Thailand enjoyed one of the world's highest growth rates, averaging 9 percent annually. Since 1995, the Thai currency, the baht, has declined in value because of inherent weaknesses in the financial sector, the slow pace of corporate debt restructuring, and a decline in global demand for Thai goods. The Thai labor force is divided among agriculture (54 percent), service industries (31 percent), and industry (15 percent). Thai industries center on travel and tourism, textiles and garments, agricultural processing, beverages, tobacco, cement, light manufacturing of jewelry, electric appliances and components, computers and parts, furniture, and plastics. Thailand is the world's second-largest tungsten producer and the third largest producer of tin.

Economic development has brought ecological problems to Thailand. The water table has been depleted resulting in more frequent droughts. There are increased automobile emissions causing air pollution in Bangkok, the capital, and in other Thai urban areas. The river systems are increasing polluted from organic and factory wastes. Deforestation is changing the geography of the nation and contributing to severe soil erosion. An increasing population clearing more forestland for cultivation is threatening the wildlife populations already endangered by illegal hunting. Thailand is a relatively homogeneous nation with 75 percent of the population Thai, 14 percent Chinese, and 11 percent drawn from other Asian ethnic groups. An estimated 95 percent of the Thai people are Buddhists and 4 percent are Muslim. The remaining 1 percent of the population is either Christian or Hindu.

Until recently Thailand's government has been a continuous series of politicians, soldiers, and bureaucrats who ran the nation with little regard for interests of the Thai people. The 1992 attempt by a military strongman to suppress student demonstrations was foiled when the King summoned the general and, in private, gave the general a severe dressing down. Democracy was restored and the immediate result was the Constitution of 1997, an extremely detailed document designed to prevent the types of governments and politicians that have governed Thailand since the 1950s. The winners were the local government and the people. Financial power is returning gradually to the provinces with an estimated 35 percent of the national budget being returned to local governments by 2006. It is the intent of the 1997 Constitution to empower the Thai voter by providing the opportunity to monitor, criticize, and challenge the bureaucracy by presenting petitions, receiving explanations from the government ministry in question, or by law suit. The constitution authorizes the creation of two independent agencies, the Election Commission and the National Counter-Corruption Commission, to ensure the integrity of the government and the constitution.

By the end of the 1980s the media regained much of its lost independence. All the major daily newspapers were privately owned, but the radio and television stations—although government controlled—were commercially run enterprises. Newspapers were enjoying their best credibility with the public. The exercise of freedom of the press in the decade of the 1980s came with a price: editorial self-censorship. The government by tradition and law does not allow criticism of the monarchy, government affairs, internal security matters, and Thailand's international image. Thailand's National Police Department has the authority to revoke or suspend the license of any publication that the government finds offensive to the monarchy's position. New press bills are pending in parliament to increase press freedom except during war or a state of emergency.

Surveys conducted in the 1980s indicated that in Bangkok 65 percent of adults read a daily newspaper whereas only 10 percent of adults in rural areas read a paper. Most of Thailand's publications are independently owned and financially solvent. Sales and advertising are their major revenue sources. The Thai government is prohibited

Radio and television stations, government controlled and supervised by agencies reporting directly to the prime minister's office, avoid controversial topics and viewpoints. Radio stations in Thailand are commercial enterprises run by the government as part of MCOT, the army, the navy, the air force, the police, the ministries of communications and education, and Courts universities. The broadcast media's operating hours, programming, advertising, and technical requirements are under the supervision of the Office of the Prime Minister. The Army Signal Corps and MCOT operate Channels 5 and 9. Bangkok Entertainment Company operates Channel 3 and Channel 7 is directed by the Bangkok Television Company. Channel 11 is a government channel dedicated to educational programming. The National Broadcasting Services of Thailand transmits local and international news on all stations.

Press Laws & Censorship

On February 2001, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra delivered a policy address to the National Assembly of Thailand. Expressed in that address were actions regarding communications policy. The prime minister proposed to promote the development of an infrastructure for a communications and transport network to improve production, create employment, and to generate income. He requested that the modernization and expansion of the telecommunications system be given the highest priority to enable each Thai citizen to receive and send information and knowledge, share linkages with other nations, and facilitate a liberalization of the telecommunications business. Government policy is designed to foster improvements in the domestic communications network and promote cooperation in building communications networks with Thailand's neighbors. Under public administration policy, the prime minister argued that improving the utilization of information technology would provide Thai citizens with comprehensive, fast and non-discriminatory information services would improve the public administration. The existing Information Act would be amended to better serve the Thai people. It was also proposed that outdated laws, rules, and regulations be changed to accommodate the nation's current economic and social conditions in order to make them more flexible to cope with Thailand's future needs.

In 2002 the media was the center of controversy for critical commentary written by the press about the King and the prime minister. The controversy directly affected both the foreign and domestic media in Thailand. In April 2002, a cable station in Bangkok had its transmission interrupted while a domestic critic of the prime minister was speaking. The station, controlled by Nation Group, a major media company in Thailand, accused the government of deliberately interrupting an interview with former foreign minister, Prasong Soonsiri, an opponent of the Prime Minister Thaksin. In 2001 Nation Group began publication of the newspaper Nation , which criticized Prime Minister Thaksin for his attacks on foreign journalists. The prime minister's office ordered an investigation into money laundering charges against Thai journalists who were also openly critical of the administration's policies. What was once perceived as a relatively free press in Thailand has thus come under attack by a prime minister who, as a successful businessman, is not used to having his policies questioned. Thailand's revered King commented in his birthday speech that the disaster facing Thailand was "from a failure to listen to criticism." Many journalists, government officials, and the Thai people perceived the King's remark as an oblique attack on Prime Minister Thaksin.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

In 2002, Western journalists in Thailand found themselves under increasing scrutiny by Thailand's prime minister. The March 30, 2002, issue of Economist , published in the United Kingdom, was blocked from distribution by the Thai government because the government was displeased with commentary about the King in the special section, "A Survey of Thailand." The government cited the article as "… affecting the highest institution [the monarchy] and tarnishes Thailand's image." Criticism of the monarchy in Thailand is punishable with up to 15 years in prison. The press restriction placed on the Economist followed an earlier incident with an article published in the Far Eastern Economic Review for making reference to alleged tensions between the King and the prime minister. The two journalists for the Far Eastern Economic Review had their visas temporarily pulled until the magazine apologized for discussing the monarchy in an article that constituted a threat to peace and the morality of the people. Thai journalists have been told not to write anything about the King and the royal family without prior permission. The Foreign Correspondents' Club of Thailand and the Thai Journalists Association have both vigorously protested to the government. The Thai prime minister told the United States not to get involved with a matter affecting Thailand's national security. The apology seems to have resolved the problem but western concern about Thailand's willingness to protect human rights is unlikely to end soon.

Thailand's prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, elected in controversy in 2001, is Thailand's wealthiest citizen. He recently acquired the only non-state-owned broadcaster ITV. Many ITV employees were subsequently fired. The press survivors were expected to take a more pro-government, non-critical position. A Thai radio station that included news broadcasts critical of the prime minister was sanctioned by the government and denied access to Nation Multimedia Group, one of Thailand's few independent news sources. Economist reporters suspect that Prime Minister Thaksin has used economic leverage against the media when his business empire distributes money for advertising. It is speculated that Prime Minister Thaksin instructs his companies to spend their advertising budgets on only friendly publications. In 2002, a polling agency's headquarters were raided after publishing a poll indicating a drop in the prime minister's popularity. Foreign journalists and their accredited publications fear that Thailand is no longer a nation that respects press and speech freedoms even when guaranteed by the constitution. Since taking office Prime Minister Thaksin has been accused of frequent critical commentary against the press, academics, businessmen, and any who criticize him. In October 2001, the Thai parliament approved a law limiting foreign ownership in the telecommunications industry to 25 percent of the company. Under public pressure the law may revert to the previously legal 49 percent allowable for foreign ownership.

State-Press Relations

Thailand's King, Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX), succeeded his brother, King Ananda, in 1946. King Ananda died under mysterious circumstances from a gunshot wound. During his reign of over 55 years, King Bhumibol has twice intervened in politics to avoid bloodshed. The first time was 1973 and most recently in 1992. Each royal intervention preserved the nascent Thai democracy from a military takeover. A televised address to the nation in 1992 strongly indicated the King's preference for democracy over dictatorship. The King remains a major force for unity among the Thailand's diverse interest groups, the commercial, industrial, and financial cliques and the military, intellectuals, and the people. Revered by his people, Bhumibol travels Thailand sponsoring projects in agriculture, the environment, public health, occupational promotion, water resources development, social welfare, and communications.

Information about Thailand's King and royal family is strictly controlled by some of the world's harshest lesemajeste laws, laws that make it a crime to violate the dignity of a ruler. Section 112 of the Penal Code sanctions punishment for lese-majeste : "Whoever defames, insults, or threatens the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent or the Regent shall be punished with imprisonment not exceeding seven years." It appears that the interpreter of Thailand's lese-majeste law is the prime minister.

When a U.S. film company decided to do a remake of the film The King and I under the title Anna and the King , the Thai government was approached about an on-location shooting of the film. Not only did the Thai government ban the film company from coming into the country, but also the film was banned from being shown in Thailand. Lese-majeste was invoked as the reason. The Thai government found the film offensive to suggest that a British governess would have had such influence over King Chulalongkorn and his family. The Thai government found it offensive to suggest that its king would associate so freely with a person not of his rank. In the recent controversy over the planned expulsion of Western journalists from the Far Eastern Economic Review and the Economist , it appears that lese-majeste was also invoked. It was the prime minister who proposed sanctions and who determines when such an offense has occurred.

There are 27 anti-press laws. Based on the 1997 Constitution, all 27 should be abolished because they contradict rights guaranteed in the constitution; however, laws are not automatically made obsolete or null and void when in conflict with a constitution. Such laws are legal and can be used to prosecute the media until each one is officially abolished by a vote of parliament.

News Agencies

There is one news agency in Thailand, the Thai News Agency, headquartered in Bangkok. Five press associations are located in Thailand's capital city: the Foreign Correspondents Club, the Journalists Association, the Press Association, the Public Relations Association, and the Reporters Association.

Broadcast & Electronic News Media

The Radio and Television Executive Committee controls the administrative, legal, technical, and programming features of broadcasting. Representatives of government agencies are selected as members. All radio stations are operated by and under the supervision of government agencies. Radio Thailand broadcasts three national programs, provincial programs, and educational programs with some programming offered in nine different languages. Television Thailand is the state television network. There are three commercial stations and an Army television channel.

MCOT, formed in 1978, is a Thai state agency that exists under the prime minister's office and is overseen by the prime minister's permanent secretary. It consists of TV Channel 9, MCOT Radio, and the Thai News Agency and employs an estimated 1,428 people. TV Channel 9 has 32 relay stations nationwide and 3 preparing to go on line in the early 2000s. TV Channel 9 reaches 96.5 percent of the Thai population presenting news as well as educational and entertainment programming. The programming is designed to encourage self-improvement skills and knowledge about Thailand in an image that will benefit the people. MCOT is the primary host for broadcasting foreign media and covers both national and international events. MCOT radio had seven FM stations and two AM stations in Bangkok; an additional 53 radio stations broadcast nationwide. Thailand's children's radio project is part of MCOT. MCOT radio provides the support for local community radio stations and encourages the population to voice their opinions and promote democracy and cultural conservatism.

The Thai News Agency (TNA) is the center of news production with the information disseminated by MCOT television, radio, and the Internet. TNA exchanges information with other members of the Association of South East Asian Nations, the Organization of Asian and Pacific News Agencies, Xinhua News Agency (China), and the Islamic Republic News Agency (Iran). MCOT's future plans include expansion into international radio and television stations by means of satellite broadcasting, e-commerce, online news and information, and digital broadcasting. MCOT currently uses the online news sites of Headline News , News DigestToday in Asean , and OANA . Portal links offered by MCOT include banks/ finance houses, e-commerce, phone messages/beepers, search engines, government agencies, job opportunities, free-addresses ISP, learning, tourist information, and

Education & Training

Thai citizens seeking a career in the media and communications can attend one of three universities in Bang-kok: Thammasat University, Bangkok University International College, and Chulalongkorn University as well as Chiang Mai University in northern Thailand. Thammasat University offers a masters degree in mass communication. The graduate program is designed to prepare students to develop communication skills and acquire sufficient experience in both theory and process, which relates to Thai society, to be equipped for future careers with a developed understanding of communication disciplines, to inform students about effective contributions to the development of the communications profession in Thailand, and to inculcate professionalism in the student's communication's major. The masters degree program is an interdisciplinary approach offering a general background in the social sciences. Emphasis is placed on critical analysis of concept, theory, and research in the mass media. The program places great emphasis on technical and practical skills. Graduate students select from three specializations: mass communication research, communication policy and planning, and development communication. Thammasat University offers a second masters degree in mass communication administration. The courses in this program of study are designed for administrators who would like to advance and enhance their understanding of the globalization process and the changing political, economic, and social factors affecting mass communication administration.

Recognizing that communication is a potent power that creates and affects social change, the Bangkok University International College offers a bachelors degree in communication arts. The undergraduate program is designed to provide students with the basic knowledge and understanding of general socioeconomic situations, prepare students in the fields of communication arts, develop graduates who are able to identify problems occurring in the society and possible solutions, develop graduates of good moral character and a sense of social responsibility, and prepare students for further study in Thailand and overseas. A graduate program in communication arts is also offered at Bangkok University International College. Students study the message and the media; relate the processes of communication to the needs of the communicators, and plan for careers in the media and communication. The graduate course of study is taught from theoretical, critical, ethical, and social science perspectives. The masters program is designed to identify and evaluate trends in social, political, and economic areas and their relevance to the aims of the technologies of communication. Graduate student majors are public relations, advertising, mass communication, and interpersonal communications.

Founded by King Rama VI in 1917, Chulalongkorn University is Thailand's oldest and most prestigious university. Donations from the Thai people erected a monument to King Rama V who offered equal educational opportunities to the Thai people. The university's basic goals are to break new ground, search for, uphold, and transmit knowledge along with ethical values to university graduates. The university's philosophy is that knowledge contributes to the prosperity of individuals and society in general and the student body and the university benefit from the diverse academic disciplines. Chulalongkorn University places significant stress on ethical standards teaching graduates self-knowledge, inquisitiveness, constructive initiatives, circumspection, sound reasoning, and a sense of responsibility, far-sightedness, morals and devotion to the common good. The university offers a bachelors degree in communication arts. Graduates of Chulalongkorn University derive benefit and status from the patronage of the Thai Royal Family and every Thai monarch of the twentieth century.

Chiang Mai University is northern Thailand's oldest, largest, and most prestigious university. International cooperation in teaching, research, and professional associations is a cornerstone of the university's academic programs. The university offers a bachelors degree in mass communication. Chiang Mai's motto "The Wise Person Cultivates Himself" promotes the university and the nation's belief that highly trained competent people are the nation's wealth. Founded in 1964, Chiang Mai's goals are to contract research, nurture culture, and provide community service. Thai graduate students may opt to pursue additional courses of study in media and communication overseas in the United States and Europe.

Summary

In the twenty-first century the government in power directly affects the degree of freedom in which Thailand's press can operate. During the last 50 years of the twentieth century there were short periods when the press published whatever it wanted to and the number of publications was large. It is true that the Thai press did not always shown restraint and responsible journalism in the types of stories it printed. There is an increasing hope that the media will show self-restraint. Historically, the print media has always been privately owned. The broadcast media is government-controlled but operated for profit. Politicians, the military, and entrepreneurs have all used the media to present particular perspectives in their attempts to manipulate public opinion.

The Constitution of 1997 is a unique document because of the detail it offers the Thai people about rights guaranteed and protected by the government. The degree of specificity was necessary to prevent the reappearance of abuses by previous governments under earlier administrations. All 336 articles in the constitution are thought to represent a mistrust of authority and a desire to spread power. The 1997 Constitution is designed to fight corruption so endemic to Thailand's political structure and the military. The constitution expresses the need to end the tradition of unstable multiparty coalition governments. By the decentralization of power from Bangkok to the provinces, the constitution's intent is to reduce the concentration of power in the capital.

Two anticorruption agencies were created by the Constitution of 1997: the Election Commission and the National Counter-Corruption Commission. A complex method exists to appoint members to each. The government plays no role in this process. The Election Commission is designed to eliminate vote buying. It seeks to reduce the influence of political parties and the traditional and frequent practice of switching party loyalties. Senators are elected without political party affiliation. The commission's rulings are final without right of appeal. The National Counter-Corruption Commission reviews the financial public disclosure of assets from elected politicians. Any errors or omissions allow the commission to ban the offender from holding the office for five years. Thailand's Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra was under investigation for failing to accurately reveal all of his financial assets. Had the commission ruled against the highly popular and newly elected prime minister, he would have been forced to step down. The prime minister was not cited or punished for his financial omissions.

The media in Thailand is not as free as they are in the Western world. It is believed that over time the Constitution of 1997 will provide the legal framework for reform at all levels of the government and full civil rights protection. Until that time, the voice of Thailand's revered King Bhumibol remains the nation's final guarantor for civil rights.

Significant Dates

- 1992: Bhumibol Adulate reverses a military coup and restores democracy.

- 1996: King Bhumibol Adulate celebrates 50 years as Thailand's monarch.

- 1997: Thailand adopts a new Constitution.

- 2001: Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra announces a major domestic agenda.

- 2002: The Thai government appears to restrict journalistic freedom of the foreign press.

Bibliography

50 Years of Reign, His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej's Accession to the Throne . Bangkok: Public Relations Department, 1996.

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, 1997.

Crossette, Barbara. "King Bhumibol's Reign." New York Times Magazine (21 May 1989): 30ff.

Insor, D. Thailand . New York: Praeger, 1963.

LePoer, Barbara Leitch. Thailand, A Country Study . Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1989.

A Memoir of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand . Bangkok: Government Printing Office, 1984.

"A Step Backwards." Economist (9 March 2002): 14.

"A Survey of Thailand." Economist (2 March 2002): 1-16.

Turner, Barry, ed. Statesman's Yearbook 2002 . New York: Palgrave, 2001.

World Mass Media Handbook, 1995 Edition . New York: United Nations Department of Public Information, 1995.

William A. Paquette

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: