United States

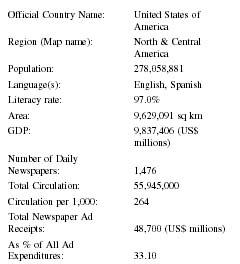

| B ASIC D ATA | |

| Official Country Name: | United States of America |

| Region (Map name): | North & Central America |

| Population: | 278,058,881 |

| Language(s): | English, Spanish |

| Literacy rate: | 97.0% |

| Area: | 9,629,091 sq km |

| GDP: | 9,837,406 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 1,476 |

| Total Circulation: | 55,945,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 264 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 48,700 (US$ millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 33.10 |

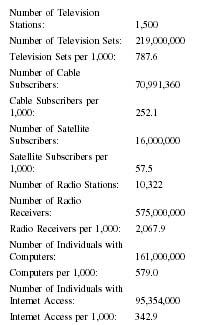

| Number of Television Stations: | 1,500 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 219,000,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 787.6 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 70,991,360 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 252.1 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 16,000,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 57.5 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 10,322 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 575,000,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 2,067.9 |

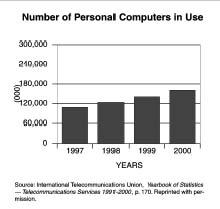

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 161,000,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 579.0 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 95,354,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 342.9 |

Background & General Characteristics

The press in the United States evolved through a long history of freedom and openness, and it operated at the beginning of the twenty-first century within one of the richest and most powerful societies in the world. Press freedom was a crucial factor in the formation of the American republic, and strict protections for the press were added to the United States Constitution just two years after it was ratified. European travelers observed the appetite for newspapers among ordinary American citizens and thought it a distinctive characteristic of the early Republic. Notably, Alexis de Tocqueville devoted large sections of his Democracy in America (1857) to his amazement at the amount of information from newspapers available to a common rural farmer.

From its independence from England into the twenty-first century, the U.S. press has operated without fear of prior restraint and with little fear of lawsuits resulting from coverage of governmental issues or public officials. Toward the end of the twentieth century, however, libel suits and libel law for private persons and corporations was less favorable to newspapers. Nonetheless, the press enjoyed broad protection that allowed aggressive reporting, including laws that sometimes mandated cooperation from public officials. The federal government and many state governments have passed freedom of information laws that require public meetings to be open and public documents to be available to citizens, including reporters, simply for the asking. In addition to assisting people in discovering facts, some states have passed laws which shield journalists from being compelled to divulge notes and information about sources, even when ordered to do so by a judge.

Nature of the Audience

The U.S. public is one of the most literate in the world, with a literacy rate reaching 97 percent. The United States also enjoys an extremely high per capita income and consumes massive amounts of media in all forms—newspapers and magazines, radio and television, and film documentaries. In 2000, 62.5 million newspapers circulated in the United States on any given day.

Though the United States has no single official language, most of the population speaks English. There is a large and quickly growing Spanish-speaking minority in the United States, concentrated most visibly in the Southwest, California, and Florida but present in all large cities and in many rural and agricultural areas. Federal and state laws compel most government documents to be published in a variety of languages. There are many non-English-language newspapers in the United States, published in a host of languages, but their quality and distribution vary widely, and their number has declined substantially since their height in the early 1900s.

The population of the United States grew steadily at a rate of about one percent per year from 1990 to 2000. The United States includes people who claim nearly every ethnic origin in the world. Although most Americans can claim some European descent, people of Hispanic origin are the fastest-growing minority group in the United States. Between 1990 and 2000, the number of people claiming Hispanic descent grew from 23 million to 32 million. Many legal and illegal Hispanic immigrants, and many citizens of Hispanic descent, speak only Spanish. The number of African Americans in the United States grew from 29 million to 33 million in that same time period.

New York City is the country's media capital and major financial center, although most of the country's movies and television programming comes from Los Angeles. The Midwest, which includes states in the Mississippi and Ohio River basins, is mainly an agricultural and industrial area. The relatively sparsely populated Great Plains states, most of which share the Missouri River basin, produce most of the country's food. About 80 percent of the country's population lived inside metropolitan areas in 1998, which comprised about 20 percent of the country's land.

Numbers of Newspapers by Circulation

Despite the growing population and affluence of the United States, many newspapers continue to suffer from declining or stagnant circulation. In 2000, daily newspaper circulation reached a low of 0.20 newspapers per capita, down from 0.30 in 1970. Fierce competition from cable channels, network television, radio, and the Internet continues to cut into newspapers' market share and circulation. Although advertising revenues continue to grow, their growth has generally been slow. The boom years of the 1990s reversed this trend to some extent, but the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States accelerated an already-existing economic slowdown and led to major declines in ad lineage and advertising revenues across the country. One positive result of the attacks, and the subsequent military response to the attacks by the United States, has been an increase in circulation, in both long-term subscriptions and daily single-copy sales. However, even this interest-driven increase was slowing as of the summer of 2002.

The general trend of the United States press over most of the twentieth century was toward consolidation, chain or corporate ownership, and newspaper monopolies in most towns and cities. In 2001, only 49 U.S. cities had competing daily newspapers. Of those 49 cities, 16 had two nominally competitive newspapers owned by the same company. Another 12 cities had competing newspapers published under joint operating agreements, an exemption to antitrust laws allowing two struggling newspapers to combine all operations outside their respective newsrooms. Only 21 U.S. cities, therefore, had true competition among daily newspapers. Of those cities, five—Tucson, Los Angeles, Chicago, New York and Seattle—had more than two competing daily newspapers, leaving 16 cities with only two competing newspapers. This number represents a massive decline from newspapers' height in the late nineteenth century, when nearly every rural town and county seat might have had two or three competing daily and weekly papers, and larger cities might have had up to 20 or 30 papers.

The number of newspapers in the United States has continued to shrink, even as the country has experienced substantial growth in population, affluence, and literacy. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the country's population was slowly aging, as a result of the post-World War II "baby boom," and older Americans have tended to be more frequent newspaper readers than younger persons.

The decline in the number of newspapers and in circulation is thus a dispiriting trend for publishers. In the last 30 years, the total number of newspapers has fallen from 1,748 to approximately 1,480. Those 1,480 newspapers are divided up into specific groups based on their daily circulation. As of Sept. 30, 2000, there were 9 newspapers that circulated more than 500,000 copies daily; 29 between 250,001 and 500,000; 67 between 100,001 and 250,000; 118 between 50,001 and 100,000; 201 between 25,001 and 50,000; 433 between 10,001 and 25,000; 363 between 5,001 and 10,000; and 260 below 5,000.

Tabloid newspapers have never been particularly popular in the United States, and most Americans tend to think of "tabloids" in terms of the supermarket alien-abduction genre of papers. However, some serious tabloids have gained a large following in certain cities; New York commuters in particular seem to enjoy the tabloidsized paper for its convenience in subway trains and on buses. As of September 30, 2000, there were a total of 51 tabloid-format papers being published in the United States. Five of those were daily broadsheet papers that published a tabloid edition only one day each week. The city with the most tabloids was New York, with four; Boston and Topeka, Kansas, had two each.

Morning, Evening, and Sunday Editions

The daily newspaper press is in the midst of a long-term conversion from publishing mostly in the evening to publishing mostly in the morning. In 1970, evening newspapers outnumbered dailies almost 5 to 1, with 1,429 evening newspapers and 334 morning papers being published. In 2000, for the first time, morning newspapers outnumbered evening, 766 to 727. In the same period, Sunday circulation grew from 49.2 million to 59.4 million, while daily circulation fell from 62.1 million to 55.8 million. Although the number of morning and evening newspapers is as of 2002 roughly equal, circulation has shifted dramatically. In 1970, evening circulation outnumbered morning 36.2 million to 25.9 million; in 2000, morning outnumbered evening 46.8 million to 9 million. Publication time roughly follows the size of the city in which a newspaper is published. As of 2002, no evening papers were published in any city larger than 250,000 people, while in towns of 5,000 or fewer, evening newspapers outnumbered morning 209 to 51. The logic of the long-term switch is complex but related essentially to newspapers' competition with broadcast media and newspapers' relationships with advertisers. Put simply, newspapers as a printed medium find it increasingly difficult to compete with television news channels on a daily basis, especially since the advent and recent massive proliferation of 24-hour cable news channels. While the afternoon or evening paper can at best summarize the events of the morning, a morning newspaper can summarize all the events of the previous day, barring sporting events or city council meetings that continue far into the night. Morning papers also are more influential in setting the tone of news discussions for the day; many broadcast reporters still get story ideas from the morning newspaper. The era of the printed newspaper as a viable medium for covering breaking news seems to be ending, although newspapers' Internet sites can be a way for papers to reclaim some of that market. In extreme circumstances press runs can be, and sometimes are, stopped or slowed, but most newspapers publish only one edition in any news cycle. The role of the afternoon paper, in the smaller communities which it generally serves, is similar to the role of the six o'clock newscast in larger cities—to provide a comprehensive summary of the day's events.

In the early 2000s, the one bright trend in circulation figures was the growth of the Sunday newspaper press. The Sunday paper is a relatively recent phenomenon, showing substantial growth in the 1980s and 1990s. As of 2002, a total of 917 Sunday newspapers were being published, up from only 538 in 1970. Most Sunday papers are published in midsize cities with populations between 10,000 and 100,000, though most Sunday circulation comes from big-city papers. Sunday papers tend to be the largest editions of the week, with papers like The New York Times publishing easily 300 pages on a single day. Sunday editions tend to be highly profitable for many papers, since they constitute a venue for a massive volume of display and classified advertising and many preprinted inserts. The Sunday paper has also traditionally contained expanded sections on science, health, books, performing arts, visual arts, TV listings, business, opinion, and the like. Additionally, many organizations use their Sunday editions for publishing expanded sections on the events of the week or for printing significantly longer stories analyzing events or trends in the public eye.

Sunday editions also often provide a place for newspapers to publish magazines, although relatively few newspapers actually produce their own. Many papers buy preprinted magazines, such as the popular Parade magazine, from news services. Many midsize and larger-circulation papers also publish a tabloid-style entertainment magazine on Fridays or weekends.

Newspaper Size

Given the size and variety of the U.S. press, there is no consistent number of pages that U.S. newspapers publish. Most midsize papers, of circulations between 25,000 and 75,000, publish between two and four news sections on any given day, with between 16 and 80 total pages. Added to the news sections can be one or two classified and display advertising sections, with between 4 and 20 total pages. Individual newspapers can even vary widely during the week in terms of their page count; most papers publish larger sections on Wednesdays,

Most morning newspapers are in large cities, and most of the circulation of newspapers comes from the big-city press. The top 50 daily and Sunday papers in the United States all circulate in very large cities. As one would expect, the number of daily newspapers is also largest in states with large populations and large geographic areas. California leads the nation with 92 dailies, and Texas is second with 87. Delaware and the District of Columbia have the fewest dailies, with only two each. Washington, D.C., though, leads the nation in circulation per capita at 1.51 newspapers circulated per person. Of course, many of those papers are bought outside the federal district's area.

Ten Largest Newspapers

The ten largest newspapers in the United States in terms of circulation are all daily papers and are all published in large cities or their suburbs. In order of circulation size as of September 30, 2000, they were: The Wall Street Journal (New York);

USA Today (Arlington, Virginia); The New York Times ; The Los Angeles Times ; The Washington (D.C.) Post ; the Daily News (New York); The Chicago Tribune ; Newsday (Long Island, New York); The Houston Chronicle ; and The Dallas Morning News . The top ten Sunday papers vary slightly from this list, due mainly to the fact that neither The Wall Street Journal nor USA Today publishes on Sunday. They are: The New York Times ; The Los Angeles Times ; The Washington Post The Chicago Tribune ;

The Philadelphia Inquirer ; the Daily News (New York); The Dallas Morning News ; The Detroit News & Free Press ; The Houston Chronicle ; and The Boston Globe .

Small & Special Interest Press

Weekly newspapers, of course, operate on an entirely different news cycle and tend to be concentrated almost exclusively in rural communities. Some weekly newspapers, such as New York's Village Voice , circulate within a larger metropolitan area and offer a serious, though sometimes alternative, look at urban news and issues, competing directly with established newspapers and broadcast stations. Most weekly papers, however, circulate in areas with too small a population to support a daily newspaper and offer their readers coverage of areas generally ignored by larger papers and broadcasters. Weekly and semiweekly papers still make up the bulk of the American newspaper press in terms of sheer numbers, although their circulation is only about half that of daily newspapers. In 2001, a total of 6,579 community weekly papers circulated in the United States. Most of those—4,145—were paid for by subscribers, and another 1,065 circulated for free. A total of 1,369 combined paid and free editions. In any given week, 20.6 million paid and 27.4 million free weekly papers circulated in the United States in 2000.

An entirely different and more recent phenomenon has been the growth of free "shopper" papers and zoned editions of larger papers. Shoppers are generally papers that are distributed free within a given market, with their production costs paid for entirely through advertising. Zoned editions, on the other hand, are bundled with the regular newspaper and generally comprise special sections that are designed to allow advertising and news departments to produce area-specific content. In other words, a large metropolitan newspaper such as the St. Louis Post-Dispatch might (and does) publish zoned editions for a variety of geographic regions and suburbs that offer coverage of local schools, development, business and other issues that do not make the regular newspaper. In 2001, some 1,399 shopper publications and 3,598 zoned editions were published in the United States.

The ethnic and religious press has been affected by the general decline of the mainstream newspaper press. The rise of the one-newspaper town, combined with the general trend towards corporate ownership and shared corporate profits, has made it more difficult for any special-interest newspaper to successfully compete for advertising dollars and subscription revenues. Special-interest publishers have tended to concentrate in the magazine sector, where narrowly focusing on a specific target market results in an ever-increasing Balkanization of the magazine medium. Not surprisingly, surviving ethnic and foreign-language papers tend to be concentrated in the large cities, where the populations they target live. In some ways, the decline in numbers of ethnic and religious papers reflects a laudable desire on the part of mainstream publishers to include all groups in their communities; however, there has been loss of unique voices in the newspaper market.

In general, the distribution of ethnic newspapers has tracked changes in the general population. The current group attracting most attention from newspaper publishers is the Hispanic market. Many big-city newspapers, and even some small-town papers in areas with large Hispanic populations, have begun publishing Spanish-language sections and tabloids, sometimes partnering with existing publications. Other newspapers targeting Hispanics have sprung up on their own in various cities. In 2000, there were 149 Hispanic newspapers published in the United States.

African Americans have long been active newspaper publishers in the United States, often because personal preference combined with real or apparent segregation made white newspaper editors reluctant to publish serious news about African Americans. Frederick Douglass, the well-known former slave and abolitionist leader, started publishing the first successful African-American newspaper, the North Star , in 1847. In 2000, some 193 newspapers aimed partially or wholly at African Americans were published in the United States.

Religious newspapers have long had a presence in the newspaper world, especially in large cities. In 2000, there were at least 127 Christian papers, mostly Catholic, and at least 75 Jewish newspapers published in the United States. Military newspapers, whether published on land bases or on large ships, make up another significant segment of the special-interest press; at least 127 military papers were published in 2000.

Quality of Journalism

One unique aspect of U.S. newspapers is their detached stance towards news and especially politics. As newspaper numbers and newspaper competition have declined, so too has the tradition of newspapers supporting a particular political party or ideology. Although most newspapers in foreign countries are generally or explicitly supportive of particular political parties, American newspapers pride themselves on their independence from the political fray. Journalists are trained to seek objectivity in their reporting and are warned against taking stances on issues, persons, or events they cover. Most newspapers, at least in theory, observe a strict separation between the news and editorial pages and maintain a strict separation of powers between the newsroom and business office. This separation of powers is meant to express papers' editorial independence and to avoid even the appearance of influences on the paper from advertisers or political parties.

Reporters and editors find a particular ethical responsibility to be as fair and accurate as possible in reporting news. Many journalists struggle to overcome their own personal biases towards the news, whether in terms of political partisanship or in terms of their own religious or ethnic backgrounds. In particular, when covering political or religious stories, journalists have to consciously remind themselves to treat all sides of an issue fairly.

What this means for most journalists is that they are either explicitly prohibited or at least discouraged from holding public office, serving as communications or public relations directors for businesses or nonprofit agencies, and generally placing themselves in the public eye as being in support of political or social issues. The logic behind these prohibitions is that while journalists are citizens and entitled to the rights and responsibilities of any citizen in an open democracy, they should not compromise even the appearance of their media organization's independence and objectivity.

In the early 2000s, however, journalists have become somewhat more visible to the public. Many newspapers consider it acceptable to sponsor public meetings dedicated to discussing an issue of public concern or to sponsor panel discussions or a series of speakers on public issues. A growing minority of journalists argues that a newspaper's civic responsibilities should be balanced against its desire to be independent and objective. Many journalists are beginning to accept the idea that newspapers should not just report on community problems, but they should be a part of a community decision-making process to fix those problems. At the same time, however, a small but vocal minority of American journalists go so far as to espouse the view that journalists should not even vote, in an attempt to strictly separate themselves from public life. Most American journalists attempt to steer a middle line, observing a strict separation between their personal, political, and spiritual lives on the one hand and their responsibilities towards a mass audience on the other.

A particular ethical problem that many newspapers face concerns relations with advertisers. Most American papers earn a large portion of their revenues from display advertising; only a very few specialty newspapers and newsletters are able to sustain themselves mostly or entirely on subscription revenues. Pressure brought against newspapers by advertisers poses particularly tricky ethical decisions at times; the newspaper may desire to be as independent as possible, but if the newspaper is forced to close, its ability to do anything ceases. This problem is particularly acute for newspapers in rural areas and small towns, which cannot rely upon support from national advertisers.

Some media critics, however, argue that most U.S. newspapers suffer from inherent biases in coverage, such as an uncritical acceptance of capitalism, free markets, and the basic two-party system, even while claiming to be objective. Corporate consolidation and the fact that as of 2002 most daily newspapers operate as only one part of giant corporations has also led many journalists to worry about the possibility of undue influence being concentrated in relatively few hands.

Three Most Influential Newspapers

By far the most influential newspaper continues to be The New York Times , which sets a standard for quality journalism unparalleled throughout the country. Although the Times is not the largest-circulation daily in the country, the influence it has on the intellectual and political world is considerable. Over the course of its history, the Times has been the newspaper of record for many Americans.

USA Today must make the top three list if for no other reason than its influence on other papers. USA Today has the distinction of being the country's only truly national newspaper; though some of its editions are zoned by regions of the country, the paper makes an effort to cover news of national importance and includes news from every state in every edition. Founded in 1982, USA Today introduced a style of news writing that emphasized short, easy-to-read stories. The paper also pioneered massive use of color photos and infographics, and it adopted a now-famous and widely copied color weather map. The focus of USA Today has never been New York Times -style investigative journalism or long series on local or national issues. The paper was, however, a success with readers, who enjoyed the use of color and its nature as a "quick read," and many of its design innovations have silently been adopted by competing papers. In fact, the last two major "gray" newspapers in the United States, the Times and The Wall Street Journal , have begun using color within the last 10 years, and many other papers have adopted some or all of the paper's innovations, such as a color weather map or daily infographic.

Rounding out the top three papers is The Wall Street Journal . A financial newspaper with a generally conservative bent, the Journal is not necessarily representative of most American newspapers, but its influence on Wall Street, and thus the world, is immense. The Journal trades the title of largest-circulation newspaper in the United States with USA Today on a regular basis. The Journal focuses mainly on business news and approaches national news from a business angle. It has, however, won several Pulitzer Prizes for reporting on non-business news. The paper also has the distinction of owning one of the few Internet sites that actually makes money; the site's content is so unique and valuable that it can successfully charge for subscriptions. The Journal is owned by the Dow Jones corporation, the publisher of the Dow Jones stock index that is used every day to track the performance of the American economy throughout the world. The Journal 's published financial data is also used throughout the country for setting a variety of loan rates, foreign currency conversions, and the like. As of 2002, the Journal 's most recent Pulitzer Prize was won for its response to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The paper's offices, across the street from the World Trade Center, were evacuated that morning and were later essentially destroyed when the twin towers collapsed. The employees of the paper evacuated en masse to the paper's printing offices in New Jersey and were actually able to improvise a paper for the next morning.

History of the Press in the United States

The first newspaper in what would become the United States appeared in Boston on September 25, 1690. Benjamin Harris published Publick Occurrences, Both Foreign and Domestic , which led with a story about Massachusetts Native Americans celebrating a day of thanksgiving for a successful harvest and went on to mention rumors that the king of France had cuckolded his son. Although Harris, the publisher of the widely-used New England Primer , was a licensed printer, his newspaper only survived one issue.

During the next few decades, several papers appeared, most published by local postmasters who had access to European newspapers and the franking privilege. The longest-lived of these early papers was the Boston News-Letter , first printed in 1704 by postmaster John Campbell. Campbell's paper grew out of a handwritten newsletter that he had distributed to postal customers. Like other papers of the time, the News-Letter consisted generally of news about politics, ship movements, proclamations, speeches, and formal letters. Campbell's paper also included news about fires, shipwrecks, piracy, accidents, and other more sensational and interesting events. Campbell's paper survived for 72 years.

By 1735, printed material was once again becoming an annoyance to at least one colonial government. The Crown governor of New York, who had been attacked in various issues of John Peter Zenger's New York Weekly Journal , prosecuted Zenger on charges of seditious libel. Under British law at that time, truth was not a defense to a charge of seditious libel. The judge instructed the jury to find Zenger guilty if they determined he had indeed printed attacks on the governor, which he undoubtedly had. Perhaps swayed by Zenger's lawyer, Alexander Hamilton, the jury ignored the judge's instructions and found Zenger innocent and freed him.

During the years between Zenger's trial and the beginning of political unrest in the colonies, the best-known paper published was undoubtedly Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette . Franklin, a brilliant polymath who consciously presented himself as a rustic farmer, won success with the Gazette and other publications because of his wry style and self-deprecating writing. Unlike his older brother James, Benjamin Franklin was also able to escape being jailed by the colonial authorities—partly by picking a city friendlier to printers.

Franklin is the best-known printer from Revolutionary days, but a host of other editors helped move the colonies closer to rebellion in the years before 1775. In 1765, Parliament passed a Stamp Act specifically aimed at taxing newspapers, legal documents, and other published materials that printers saw as intended to drive them out of business. The short-lived Stamp Act was only the first in a long series of measures designed to tax colonists for supporting British troops in North America that eventually led to rebellion, but it was a significant moment in radicalizing editors against the British government.

Newspapers were only one weapon in the general colonial protest against Britain, but they were a surprisingly effective one, being able to carry news of demonstrations, mock funerals of "Liberty," news of real and perceived abuses against colonists, and perhaps most importantly news from other colonies. The same printer-editors who published newspapers were also responsible for printing and distributing the variety of pamphlets, broadsides, engravings, woodcuts, and other miscellaneous propaganda distributed by revolutionary "Committees of Correspondence" from many of the colonies. During this same period, of course, loyalist printers also published material in support of the British government, and some very conservative editors avoided news of the conflict altogether or swayed back and forth as local political winds dictated.

The most well-known colonial protest against the British government, the Boston Tea Party, is an example of how newspapers helped radicals spread their message. The men who participated in the famous party may have planned their raid at the home and office of the printer Benjamin Edes of the Boston Gazette . Edes' Gazette and other papers printed full accounts of the attack and, more importantly, the rationale behind it, which were clipped and reprinted by other colonial newspapers, spreading the news farther across the colonies at each printing and in a sense recreating the event for each new reader. Without the intervention of the press, the Boston protest, and countless others in the colonies, would have been no more than an example of local hooliganism.

During the Revolution itself, printers of all political orientations found themselves even more closely tied to the fortunes of war. Editors often were forced to flee before approaching armies, and presses—especially Tory presses—became the focus of mob violence on more than one occasion. In addition, the British naval blockade and general economic disruption caused by the war made it more difficult for editors to find supplies and to publish on anything approaching a regular basis. But newspapers had done their work; when John Adams wrote that "The Revolution was effected before the war commenced … this radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments and affections of the people, was the real American Revolution," he referred to the work done not only by the Sons of Liberty and Committees of Correspondence, but also that done by colonial editors.

American independence resulted in a reshaping of the press. For a short time, freed of the war-driven impulse to produce patriotic material, printers reverted to the pre-Revolutionary model of commercialism and relative political neutrality. The upcoming Constitutional Convention and the ratification debates attendant to it, however, meant that editors would once again shift into a more public, political role. A new generation of editors would radically transform their newspapers, create new political roles for themselves, and eventually lay the foundations for the American party system in the years between 1790 and 1830. To understand that transformation, it is important first to examine the social role of printers in colonial and Revolutionary times.

Franklin's example notwithstanding, being a printer in colonial days was hardly a road to political power, prestige, or riches. Although printers were valued by their towns, and their business brought them into contact with the local elite, they were still artisans, sharply separated from the colonial gentry by class, manners, refinement, and occupation. Printing was a difficult and often disgusting business. The youngest apprentice in a colonial office would often be given the job of preparing sheepskin balls used to ink the type. The balls had to be soaked in urine, stamped on, and wrung out to add softness before being brought to the press. Ink was often made in the office by boiling soot in varnish. More experienced printers might spend up to sixteen hours setting type, reading copy with one hand while the other selected individual letters and placed them, backwards and reversed, into a typecase.

The locked typecase—essentially a solid block of lead type with wood frames—would be carried to the press by hand, the type itself beat with inked sheepskin balls, and the press cranked by hand to bring the plate into contact with a sheet of wetted paper. This process would produce one side of one sheet—one "impression." The sheet would then be hung to dry, and the inking, wetting, and cranking process repeated. Two experienced printers could produce about 240 sheets an hour at best. Later, they would repeat the entire process, including setting new type, for the other side of the sheet, and later fold the papers by hand. The total process of producing a rural paper with 500 to 600 copies would take at least a day and most of the night.

During the years immediately following the Revolution, printers' status actually declined throughout the country. As the process of creating a newspaper became more specialized, the job of actually printing a newspaper became increasingly divorced from the process of writing and editing the news. During the 1790s, this trend became more distinct as a new breed of editors turned away from the trade-oriented, mostly commercial, goals of their predecessors. Younger men found themselves increasingly drawn to partisan controversies and found their true calling in editing political newspapers.

From the late 1790s on, partisan newspapers became increasingly more crucial to politics and politicians in America. Partisan newspapers acted as nodal points in the political system, linking ordinary voters to their official representatives and far-flung party constituencies to one another. Political parties existed without formal organization in the early Republic, and partisan newspapers provided a forum in which like-minded politicians could plan events, plot strategy, argue platforms, and rally voters in the long intervals between campaigns and events. Physical political events like speeches, rallies, and banquets with their attendant toasts could only reach a limited number of voters at any given time, but when accounts of them were printed and reprinted in newspapers their geographic reach was vastly extended. In the days before formal party headquarters, local newspaper offices functioned as places in which politicians and editors could meet and plan strategy.

Throughout the nineteenth century, newspapers remained the focal points of political struggles, as parties and factions battled for control of prominent newspapers and regions. Newspapers could also come before formal party organization, as when William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator made him the leading figure of the abolitionist movement and predated the founding of his New England Anti-Slavery Society by a year. When black abolitionists wanted a voice in the movement, they attempted several times to found a newspaper, finally succeeding in 1847 with Frederick Douglass's North Star .

Later journalism historians searching for the origins of objectivity and professionalism would often find their origins in the penny press, started by James Gordon Bennett's New York Sun in 1833. The penny press, which owed its name to the fact that penny papers sold for one or two cents daily, instead of several dollars per year, was more stylistically than substantively different from the partisan newspapers of its day. Bennett and other editors made much out of the fact that they were "independent" in politics, but by independence they meant essentially that they were not dependent upon one party for support.

What the penny press actually did was to combine and extend many of the innovations with which other newspapers were beginning to experiment. The penny papers popularized daily copy sales rather than subscriptions, relied more upon advertising than subscriptions for support, and broadened the audience for reports on crime, courts, Wall Street, and Broadway. The penny papers also continued a process of specialization that led eventually to the "beat" system for reporters and to changes in the internal organization of newsrooms. But the penny press was a uniquely Eastern and urban phenomenon which was evolutionary rather than revolutionary in press history.

In the 1850s and 1860s, sectional politics dominated newspapers, as radical stances began to be taken by all sides on the question of slavery. After the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, eleven Southern states decided to leave the Union, making civil war inevitable. During the war years, newspaper editors often found themselves caught between competing sectional and party loyalties, especially in border states like Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland, while other editors found their papers suppressed by local authorities or by invading armies. Southern editors in particular faced hardship during the war, as the northern blockade dried up the supplies they needed to publish. Other papers, especially in the North, were able to continue their vigorous partisanship; Lincoln wryly noted that even Horace Greeley's Tribune , a Republican and abolitionist paper, only supported him four days a week. Newspaper correspondents vastly expanded their use of the telegraph and photography in reporting on the war; a new genre of "illustrated magazines" made copious use of both picturesque and horrible war scenes.

In the years after the Civil War, the tremendous growth in newspapers that the nineteenth century had seen slowed somewhat. The United States grappled with a deep economic depression throughout the 1870s, and most of the South was still under military occupation. The African-American press was one sector that showed growth in the years after the Civil War, as freed slaves, most of whom had been prevented from learning to read or write, came together to create their own schools, banks, newspapers, and other public institutions. Once again, major new political movements found expression first in partisan newspapers. Editors continued to take strong stands on national political events as well, with the impeachment and trial of Andrew Johnson and the increasingly corrupt administration of Ulysses S. Grant at center stage.

During the 1880s, massive changes were underway in the United States that would change the nature of newspapers and of news in the twentieth century. The U.S. economy had recovered from the depression of the 1870s and was beginning to embark on the great decades of industrial expansion that would make it the world's leading economy by the 1940s. Immigrants once again began to flood into eastern cities, accelerating an existing trend towards urbanization and creating a huge demand for foreign-language newspapers. The 1890 census for the first time counted more Americans living in cities than in rural areas. The 1890s in general would become known as one of the most flamboyant eras of American journalism, marked by incredible competition among the large urban dailies.

The two most famous representatives of the newspaper wars of the 1890s were Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. Pulitzer, a Hungarian who had immigrated to the United States to fight in the Civil War, bought the failing St. Louis Westliche Post , a German-language Liberal Republican newspaper, at a sheriff's sale in 1878, later combining it with the St. Louis Dispatch . Pulitzer's Post-Dispatch , which changed political orientations when Pulitzer himself became a Democrat, became a model for the kind of crusading urban newspaper that he would later run in New York. Attacking political corruption, wealth, and privilege, Pulitzer sought to create and unify a middle-class reform movement in St. Louis. When he bought the New York World in 1883, his goal was again to rescue a failing newspaper by launching it on a progressive political crusade, partly by supporting issues important to the city's large immigrant population. Hearst, the son of a wealthy California mine owner, actually got his start in journalism working for the World before purchasing the San Francisco Examiner in 1887. When Hearst returned to New York, it was as a direct competitor to Pulitzer. Hearst used his Morning Journal to attack Pulitzer, the city government, and anyone else who caught his eye, and later to encourage the United States to declare war on Spain in 1898. The circulation wars of the 1890s, which led to extremes of sensationalism later called "yellow journalism," pushed both papers' circulations above one million at times.

The period between 1890 and 1920 is also notable as an era in which individual reporters became more well-known than ever before. The era of "muckrakers" is difficult to characterize as a unified set of ideas, but most muckrakers shared a general desire for social reform, a faith in the ability of government and society to overcome problems, and a belief that their exposés would result in action. The topics muckrakers tackled ranged from Ida B. Wells's courageous work to ending lynching in the South to Jacob Riis's portraits of homeless youths in New York. At the other end of the spectrum rest journalists like Lincoln Steffens, whose "Shame of the City" series is representative of a genre that tended to focus on the personal habits and customs of the new immigrants peopling urban areas, and to blame urban corruption, homelessness, poor sanitation, and other urban problems on the ethnic or racial backgrounds of those immigrants.

The years leading up to World War I in many ways marked the high point of the newspaper press in the United States. In 1910, the number of daily newspapers in the United States peaked at 2,600; in 1914, the number of foreign-language dailies in the United States reached a high of 160. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson set up the Committee on Public Information, headed by George Creel, to rally press support for the war effort. Creel's committee used a newly passed Espionage Act to limit publication of materials that questioned the war effort, mainly by revoking papers' mailing privileges. Particularly hard-hit was the Socialist press, which in 1913 had counted 323 newspapers with more than two million copies circulated daily, but other non-mainstream newspapers were also attacked by the government.

Although the Creel Committee relied more on voluntary compliance than on federal enforcement, the effort put forth by the government to bring media in line with the war effort led many editors to question the veracity of news told in support of a single point of view. This trend, combined with a general postwar disillusionment towards extreme political and social ideas, accelerated an existing trend towards the objective model of newsgathering. Although the "who, what, when, where, why and how" model of reporting had existed since at least the 1890s, the 1920s marked the first widespread acceptance of objectivity as a goal among newspapers. Increasingly fierce economic competition between newspapers and declining readership also contributed to a trend towards objective reporting; the role of corporate advertisers in supporting papers also encouraged nonpartisanship on the front page. The rise of the one-newspaper town coincided with a shift in thinking on the part of editors, who had to begin seeing their readers less as voters and more as news consumers. As always, objectivity became accepted as a news model first among large urban papers, only slowly making its way into the hinterlands.

The 1920s saw a continued decline in the number of daily newspapers but also the advent of new technologies that would eventually vastly change the news. The first commercial radio station in the United States, KDKA in Pittsburgh, made its debut broadcasting results of the Harding-Cox presidential election in 1920. By 1922, the number of stations had increased to 576, and over 100,000 radios were bought that year alone. The new technology did not at first massively change newspapers, but its popularity combined with continued declines in newspaper readership foreshadowed trends that would continue throughout the twentieth century. In 1926, when Philo Farnsworth first experimented with television sets, 5.5 million radios were in use in the United States.

The 1930s brought the Great Depression to the United States, and newspapers suffered along with the rest of the economy. The American Society of Newspaper Editors led many influential papers in opposing Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal programs. The defining Supreme Court decision concerning newspapers, Near v. Minnesota , was heard in 1931. In Near , the court held that First Amendment protection against prior restraint extended to prohibit state and local governments, as well as the federal government, from prohibiting publication of a newspaper on any but the most unusual circumstances.

The Depression resulted in a slowing of growth for radio as a medium, but the 1930s also saw the consolidation of stations into national radio networks and the expansion of those networks across the country. The demand for simple, concise reporting for radio news programs helped to push newspapers in the direction of the inverted-pyramid style of writing and did much to institutionalize the cult of objectivity. In addition, federal courts began to allow radio broadcasts and station licenses to be regulated by the government, holding that the radio broadcast spectrum rightly belonged to the public and could be regulated in the public interest. Roosevelt's "fireside chats" used the new medium as a way to communicate directly to the people, contributing to a general 1930s trend towards increasing the power of the federal government relative to the states.

The end of the 1930s saw the advent of World War II in Europe and a growing strain of isolationism in the United States. Many newspapers initially opposed U.S. involvement in the European war, but that opposition evaporated after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

At the beginning of the war, newspapers agreed to voluntarily censor their content under a Code of Wartime Practices developed by Byron Price, a former Associated Press editor. Many newspapers also printed information distributed by the Office of War Information, headed by Elmer Davis, which was a government body set up to disseminate morale-boosting material. World War II newspapers did not generally suffer from the same constraints as papers did under the Creel Committee in World War I, partly because World War II had significantly more support from the general public and from newspapers, and partly because no World War II counterpart of the Espionage Act was used to attack non-mainstream papers. The general economic dislocation caused by the war did cause, however, many newspapers to suspend publication. By the end of 1944, there were only 1,745 daily newspapers being published in the United States, a loss of 360 from 1937.

An important postwar development in newspaper journalism was the Hutchins Commission's report on "A Free and Responsible Press." The report, which argued that a free press had a duty to responsibly report news without scandalmongering or sensationalism, became an important statement of ethics, putting into words the philosophy that the United States press had been groping toward since the 1920s.

On July 1, 1941, two television stations in New York began broadcasting news and programs to tiny audiences in the city. Though television began as a tiny medium and though the war hampered its ability to grow, the new medium expanded rapidly after the war. By 1949, there were more than 100 television stations in the country. The growth of television hurt newspapers, though not as much as was initially predicted. The real victim of the popularity of TV, though, was radio. In the 1950s, many radio stars, including Edward R. Murrow, abandoned radio for television, and radio began to lose its appeal as a mass medium. Radio pioneered the practice of "narrowcasting" starting in the 1950s, as stations abandoned nationally produced content to focus on a specific demographic or ethnic group within its listening area. This early and successful form of target marketing predated and pres-aged efforts by magazines and some newspapers to do the same.

The 1960s were generally a decade of massive change for newspapers. Typesetting changed dramatically as the use of photocomposition and offset presses became widespread. The advent of offset spelled doom not only for the jobs of Linotype operators but also for many other specialized printing trades. The result was a rash of newspaper strikes that continued into the 1970s. Some of the cities struck were Boston, Cleveland, Detroit, New York, Portland, St. Louis, St. Paul, San Jose, and Seattle. The Detroit News and the Detroit Free Press were shut down for 267 days in 1967 and 1968.

The 1970s saw one of the most dramatic instances of the power of the United States press when the Washington Post 's coverage of the Watergate burglary started a process that led to the resignation of President Nixon. The 1970s were also notable as the decade in which computers first began to invade U.S. newsrooms. Though slow and balky at first, computers would revolutionize typesetting by the 1990s, with later technology making it possible for type to go directly from computer screen to printing plate. The continued decline in multiple-newspaper cities led Congress to pass the Newspaper Preservation Act of 1970, which allowed competing newspapers to merge essentially all of their operations outside the newsroom if one or both were in financial distress.

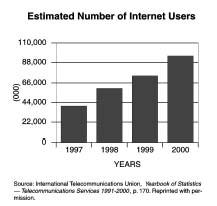

The 1980s brought more massive changes to the media in the United States. The first all-news TV network, CNN, debuted in 1980, and the first new national newspaper, USA Today , was first published in 1982. Though both were at first derided by the newspaper press, both survived and prospered. CNN offered the world live coverage of the Gulf War in 1991, and viewers experienced watching U.S. bombs drop on Iraqi targets live and in color. The 1990s will be remembered most as the decade in which the Internet exploded as a major cultural force. Newspapers were quick to build Internet sites and invest in the new technology as part of a "convergence" strategy, although as of the year 2002 profits from the Internet continued to elude most companies.

Increasing consolidation of newspaper chains and ever-decreasing competition have been other major trends of the 1980s and 1990s, with newspaper mergers and buyouts continuing unabated. The booming U.S. economy of the 1990s and the over-inflated stock market undoubtedly contributed to this trend. The largest recorded value of deals struck for newspapers in a single year occurred in 2000, with a total of $15 billion changing hands. Between 1990 and 2000, newspaper companies aggressively sought to expand their holdings in both numbers of newspapers and in specific geographic areas, seeking especially to cluster their holdings in and around metropolitan areas. Newspaper companies also aggressively expanded into television, radio, and the Internet, with mixed results. At the end of 2000, the top 25 media corporations controlled 662 U.S. dailies with a combined daily circulation of 40 million.

Economic Framework

Overview of the Economic Climate and its Influence on Media

The information industry in the United States is one of the most dynamic and quickly-growing sectors of an economy that was struggling to recover from recession in the middle of 2002. The prior economic census of the United States, taken in 1997, listed 144,000 businesses devoted to information and communications, with more than $623 billion in gross receipts. Of those businesses, 8,800 were newspaper publishers, with total revenues of $117.3 billion. In 1999, newspaper-publishing companies had about 400,000 employees and carried a total payroll of $26 billion. To say the least, communication industries are not an inconsiderable part of the U.S. economy.

Since 1997, the United States experienced a massive speculative boom in the stock market, fueled mainly if not entirely by companies that promised to use the limitless potential of the Internet to deliver every possible type of service to the home consumer. That speculative bubble burst in the first half of 2001, shortly after the contested George W. Bush versus Al Gore presidential election was finally decided. Uncertainty over the future course of the country, combined with a growing impatience with seemingly empty promises from Internet companies, caused a massive contraction in equities markets throughout 2001 and sent the U.S. economy into a recession.

The business climate was still stagnant in September 2001, when terrorists struck at the heart of the U.S. financial system in attacks that killed nearly 3,000 people, devastated the financial district of New York, shut down the U.S. air travel system and the U.S. stock exchanges for days, and caused a massive wave of panic to ripple throughout the country. The economic news was improving somewhat in the summer of 2002, but the long-term outlook remained uncertain.

The falling stock market affected not only Internet companies but other corporations as well, including publicly-held media companies and many of their major advertisers. Many media companies were already coming to terms with falling advertising revenues before the terrorist attacks. The aftermath of September 11 caused businesses to rethink capital expenditures and shift comparatively more money into security-related spending and less into advertising. Newspapers were hurt by declining advertising but were helped somewhat by a rise in newspaper circulation since the attacks and subsequent U.S. military campaign in Central Asia. However, as of the summer of 2002, those short-term circulation gains seemed to be evaporating.

Newspapers in the Mass Media Milieu: Print Media versus Electronic Media

Newspapers make up only one portion of the mass media in the United States, and they make up a declining percentage of the media market. Although the 1997 economic census listed 8,758 newspaper publishers (including daily and weekly papers) and 6,928 periodical publishers, it also listed 6,894 radio broadcasters; 1,895 television broadcasters; 4,679 cable broadcasters; and 14,895 information and data services processing firms. With the recent growth of Internet businesses, print media are taking up an ever smaller share of the media audience.

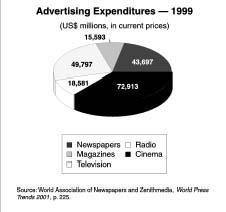

Although both print and broadcast revenues continued to grow throughout 1998 and 1999, the rate at which newspapers grew, 6.8 percent, is only .4 point ahead of television growth (6.4 percent) and is only about half the rate of radio growth (12.5 percent). By comparison, information and data processing services grew 28.2 percent, and online information services grew by 69.5 percent. Although newspapers still outstripped online services in 1999 in total revenues, $48.5 billion to $21.1 billion, the phenomenal growth of online services implies that newspapers' dominance is limited. Newspapers also had slightly more revenue than TV and radio broadcasters, which had revenues of $47.6 billion in 1999.

One bright spot in the comparison of newspapers to broadcasting agencies has been that newspapers are generally retaining readers better than broadcasters are retaining viewers. In the summer of 2002, the news organizations of the three major networks all reported precipitous declines in the number of viewers their news programs were able to capture.

Types of Newspaper Ownership

Most newspapers in the United States are part of newspaper chains, owned by corporations that control from two to several hundred papers. Although some newspapers are still held privately or controlled by families or trusts, the trend of corporate ownership proliferated in the 1980s and 1990s. A total of only ten companies own newspapers that account for more than half of the United States' daily circulation, and three of those ten companies are privately held. As of May 2001, the top three newspaper companies—Gannett, Knight-Ridder, and the Tribune Co.—owned one-seventh of all daily newspapers, representing one-fourth of the circulation of U.S. newspapers.

In the early 2000s, chain ownership was one of the most hotly debated trends in the United States media. Critics of chains worry about consolidating so much circulation, power, and influence in the hands of a relatively few people, charging that corporate newspapers accept a corporate mentality that substitutes concern for profits and stock prices for journalistic integrity and independence. Another concern is corporate standardization. Recently, Knight-Ridder raised eyebrows across the journalistic world when it converted all of its newspapers' Internet sites to a standard corporate model, including that of the San Jose Mercury-News , which pioneered Internet newspapers. The newspapers' "Real Cities" sites, which are at Web addresses such as kansascity.com and charlotte.com , subsume the newspapers' identities entirely within the context of the corporate, "Real Cities" brand, identifying the papers themselves only vaguely and giving those newsroom teams relatively little credit for the product they produce.

One major consequence of corporate buying is that early 2000s sprees inflated the value of newspapers out of proportion to their actual profit margins. With corporate owners increasingly concerned about servicing their debts, cost cutting seems to be the only way to ensure a cash flow great enough to meet obligations to debtors. More often than not, this means staff cuts, since the major cost centers in newspapers are people and newsprint, and newsprint costs are constant and generally rising.

Of particular concern to many observers of the media scene is the increasing proportion of publishers and even general managers who come from a background in business, instead of in journalism. There is a prevailing feeling among many editors that an MBA may qualify a person to run a business but that a publisher with a business background may subvert the interests of the newspaper and its editorial independence. Of particular concern are the effect of corporate decisions on editorial content and the question of whether editorial matters may be subverted in the interest of or at the request of advertisers and other business interests of the corporation.

Some journalists have increasingly insisted on making a "full disclosure" when reporting or commenting on movies, books, or programming produced by another arm of a massive corporation. A good example would be a commentator for Time criticizing a movie produced by Time Warner, Inc., noting in his or her article the corporate ownership of both types of media. This type of disclosure, however, is only helpful in allowing those readers who were not aware of such cross-ownership to find out about it in the act of reading; it does not provide insight into the editorial decisions that produced the article or commentary in the first place, and it leaves the magazine or newspaper open to concerns of undue corporate influence.

On the other hand, corporate ownership may actually benefit many small-to medium-sized newspapers by creating a company-wide pool of resources and talent that the company can draw upon to make individual newspapers better. Corporate ownership can mean corporate discounts on newsprint, ink, printing presses, and other supplies, and can mean skilled help from within the corporation when presses break, lawsuits are threatened, or disasters strike newspapers. Corporate ownership combined with public financing can also mean that companies have an available pool of money from which to draw for special projects, better coverage, and the hiring process.

Effects of Corporate Ownership

The individual effect of corporate ownership undoubtedly varies from company to company and from newspaper to newspaper. Some papers that operated alone at a very high level might find themselves stifled by a corporate mindset that asks publishers to justify any expense to the head office; on the other hand, an infusion of corporate money, talent, and resources is a godsend to any number of struggling papers.

However, the experience of being bought and sold invariably leads to a period of uncertainty for employees of a newspaper, as the new company generally makes changes in the management structure, management philosophies, and management personnel, to say nothing of other hirings and firings that may affect jobs and morale in the newsroom and in the rest of the paper. Small changes are magnified at small newspapers, which generally have smaller staffs than larger-circulation papers and are thus more likely to be affected by cuts that could be thought insignificant at larger organizations. Half of the newspapers in the United States have circulations below 13,000 readers, and of those papers fully 47 percent changed hands in the six years between 1994 and 2000.

One unique exception to corporate ownership, and one way that some multi-newspaper cities have managed to keep operating, is through joint operating agreements (JOAs). Created in 1970 as an exemption to anti-trust laws, JOAs allow two or three competing papers to merge business and production operations while keeping news-rooms separate and continuing to produce multiple newspapers. There have been 29 JOAs in the United States since the law was passed; 12 still survive. Of the others, all except two ended with one newspaper failing, moving to weekly publication, or merging with the other paper.

Press Media and Electronic Media Audiences

The U.S. newspaper audience is more affluent, well-educated, older, and better employed than the general population, according to a 2000 Mediamark, Inc. survey that tracked participation in media in a given week. About 79 percent of American adults had looked at a newspaper within the past week at the time of the survey. Of people who had a college degree, 89.7 percent had looked at a newspaper, compared with only 60 percent who were not high school graduates. About 83.5 percent of people age 45 to 54 had read a paper, compared with 73.3 percent of people age 18 to 24. Interestingly, white and black Americans read newspapers at equal levels: 79.3 percent of whites and 79.2 percent of blacks had looked at a newspaper.

The same survey found that people who were more poorly educated watched slightly more television; 94 percent of people without a high-school degree watched television in the past week, compared with 91.1 percent of people with college degrees. Income had little effect on television viewing, but it did have a dramatic effect on Internet usage. Only 14.6 percent of people who made less than $10,000 a year had used the Internet within the last month, while 67 percent of people who made more than $50,000 a year had logged on. Interestingly, however, usage dropped precipitously among people making $150,000 a year or more, falling to just 7.6 percent of that population. Education levels made an even more dramatic difference; only 11.6 percent of people with no high school degree had used the Internet, compared with 76.5 percent of people with college degrees.

Advertisers' Influence

Advertising revenues remain a major concern for newspaper publishers. In 2001, the last year for which figures were available, newspapers saw a precipitous drop in advertising expenditures on the part of businesses. Retail, national, and classified advertising fell each quarter compared with the same quarter in 2000, which was itself down compared to 1999 spending. Total advertising expenditures fell 4.3 percent in the first quarter, 8.4 percent in the second, 10.3 percent in the third, and 11.9 percent in the fourth, for a total year-to-year decline of 9 percent overall. Classified advertising, which comprises the bulk of most small newspapers' ad revenues, took the greatest hit, declining 15.2 percent from 2000. National advertising fell by 8.5 percent, while retail advertising fell only 3.4 percent. Total ad revenues, in dollar terms, fell from $48.670 billion to $44.318 billion.

The drop in advertising revenues year-to-year has been of great concern to publishers, who rely on advertising for most of their profits. Short-term circulation gains have been evaporating at many newspapers, and many papers continue to face shrinking circulations and the prospect of falling ad revenues as well. Any cuts that come out of papers have to come from within, with employees bearing the brunt of the cuts.

Most newspapers still strive to maintain at least a 1:1 news-advertising ratio. This means in general that news and advertising lineage—a somewhat archaic term— should be approximately equal throughout the newspaper in order for the day's advertising to pay for the daily press run. Ideally, the ad ratio should be skewed slightly farther in the direction of advertising in order to maximize profits and to cost-justify the number of pages appearing in a paper, but most newspapers will generally provide an "open page" when the city desk asks for more space for a certain package of stories or for a long-standing special report. Needless to say, such a ratio is not achieved every day, nor is it achieved through display advertising alone. Weekly inserts and changes in the number of ads placed in the paper day-by-day have a large effect on papers' ad ratios.

With a large portion of a newspaper's revenues coming from advertising, it is no surprise that advertisers sometimes attempt to influence editorial policy, especially with regard to stories that have the potential to adversely affect their businesses. Pressures from individual advertisers can sometimes sway weaker or smaller newspapers to change editorial coverage or even abandon stories entirely. The effect of such pressure, as one might imagine, depends almost entirely upon the portion of a paper's revenue that an individual advertiser provides; the relative editorial strength and independence of the paper's owners; and the newspaper's standing in the community.

Influence of Special Interest Lobbies

Another collection of groups that may affect newspaper coverage of certain events is the various special-interest lobbies that exist across the country. Lobbying organizations command a disproportionate amount of newspaper coverage compared with their actual power and the amount of the population they represent essentially because of their skill at "working the media" and ensuring that they provide

Employment and Average Wage Scales

Though newspaper audiences tend to be more affluent than the rest of the population, newsroom employees tend not to be particularly well-paid compared to other groups. Exact data for newspaper pay scales can be difficult to come by, given that the Census Bureau does not break down wage data from the communications sector to specific categories or wage levels within individual communications sectors. However, wage data taken from the Economic Census of the United States, taken in 1997, suggest that newspaper workers in general are paid well below the more general communications sector and slightly below the average wage for the rest of the United States.

According to the Economic Census, the average pay per worker in the entire communications sector is $42,229 per year, with newspaper workers receiving $29,228 per year. This puts newspaper workers below the average for all newspaper, periodical, book, and database publishers, which average $33,753 per employee per year. By comparison, periodical publishers' workers average $43,500 per year, with book publishers' employees averaging $40,522 per year. Database workers average $38,400 per year, while software publishers' employees make about $69,000 per year.

To expand this view to other forms of media, we find newspaper workers again near the bottom of the pay scale. Motion picture and sound recording workers average $34,000 per year, while television broadcast workers average $50,900 per year. Only radio broadcasters average less than newspaper workers, making about $28,455 per year. The average hourly pay for newspaper employees in 2000 was $14.05 per hour, compared with $13.74 for the entire private sector. However, the average 1999 salary for a full-time worker in the United States was $36,555, placing newspaper employees well below average salary levels.

Strikes and Labor Unions

Between 1990 and 2002, there were two major newspaper strikes in the United States, in Detroit and in Seattle. There were also minor work stoppages at several newspapers, and as of the summer of 2002, there was a curious "byline strike" ongoing at the Washington Post . The relatively small number of strikes in the 1990s partly reflects the economic boom of the decade and partially reflects the dwindling influence unions have over the press.

The major labor unions in the U.S. press have always been somewhat divided between two groups, corresponding roughly to their members' place in the newsroom. One group of unions represented compositors, typesetters, printers, and other persons who were skilled laborers mainly in charge of actually printing the paper. The other group of unions, of which the Newspaper Guild is the survivor, represented reporters, copy editors, and photographers—once blue-collar, hourly-wage occupations that over the course of the twentieth century gradually became white-collar, professionalized, salaried jobs.

Offset technology utterly erased jobs once held by compositors and typesetters, and it took much of the older type of skilled labor out of printing. The elimination of lead type in favor of offset plates means that copy editors and designers can now typeset a page in one computer mouse-click. In the 1990s, newspapers gained the capability to create negatives and even press plates directly from the newsroom, eliminating the legions of skilled workers once needed to make that transition. The new offset presses also brought with them a dramatic fall in labor costs; although Ben Bradlee was wrong when he observed that one man could push a button and a newspaper would be printed, the offset presses do require much less labor to run. Printers' unions still represent the men and women who run offset presses, but their jobs have become more easily replaceable over time. In addition, the fact that as of 2002 large corporations held most newspapers shifted the balance of power decisively in favor of management; companies in the early 2000s have large pools of employees and deep pockets whose reserves that they can use to break a strike.

The Newspaper Guild also has seen a decline in its relative importance and its membership. The Guild was formed in 1933, and members once identified closely with printers and other hourly-wage workers and against their editors and the newspaper's management. Ironically, though, increasing job mobility and wage scales for reporters, editors, and photographers have increased class distinctions between the newsroom and the pressroom. In addition, the growing importance newspapers place on individual reporters, and the recent phenomenon of reporters becoming stars in their own right and being promoted as a result of their reporting, has meant that the ranks of management are increasingly filled with those who once were reporters and editors, blurring distinctions even further. The Guild's membership peaked at 34,800 in 1987 and has been falling ever since. Overall, the percentage of newspaper workers who are union members has dropped from about 17 to 20 percent in 1975 to about 10 percent in 2000.

The largest newspaper strike of the 1990s illustrates these trends in dramatic fashion. In 1990, the Detroit Free Press and the Detroit News entered into a joint operating agreement. After the JOA, trumpeted by both papers' owners as a cost-saving measure, newsroom workers got an average raise of only $30 per week. Tensions in both papers simmered until July 13, 1995, when 2,500 employees of both papers, represented by six unions, walked off the job.

Gannett and Knight-Ridder, publishers of the News and Free Press , both vowed to continue publication and did. Strikers encouraged union workers in Detroit, a union-heavy and union-friendly city, to boycott the paper, and they did. The result of the strike was disaster for both sides, as circulation, advertising dollars, news-room morale, and salaries all fell. The strike lasted for 19 months, or a total of 583 days. By October 1997 some 40 percent of striking workers were back on the job, but the newspapers continued to struggle. The walkout cost the papers about $300 million, mostly on replacement workers, loss of goodwill, and lost advertising revenues. The papers saw a 280,000-paper drop in circulation, which as of 2002 had not been regained. The unions failed to shut the newspapers down, and the papers have been slow to rehire union members, many of whom took jobs elsewhere or moved out of the newspaper business. The lasting result of the strike has been bitterness and acrimony on both sides.

Following the Detroit strike, the only other major strike as of 2002 was in Seattle, where employees of the Seattle News walked out over a new contract at the end of 2000. The Seattle strike lasted 49 days, and ended at last when the Guild accepted a contract that was essentially identical to the one it had rejected initially.

An interesting development in recent years has been the resurgence of "byline strikes," whereby reporters, columnists, and sometimes photographers refuse to publish bylines with their stories. The impact on a paper's credibility is hard to gauge, though readers have reported frustration in their inability to identify writers and thus their inability to effectively complain about stories that they might not like. The concept of a byline strike was resurrected in New Jersey in April of 2001, where Jersey Journal employees began a byline strike after the paper offered them annual raises of $2 per week. Subsequently, on June 5, 2002, Washington Post employees staged a by line strike to protest the Post 's policy that they write stories both for the newspaper and for the Post 's Web site. The Newspaper Guild called on reporters to delete their bylines both from the paper and from the paper's Web site. The Post was the first newspaper to attempt such a strike, in 1987, and the effect was mixed at best. Many observers have pointed out that most readers tend to ignore bylines in any case, with the obvious exception of syndicated columns. In 2002, the effect of the Post employees' effort remained to be seen.

Circulation Patterns and Prices

Newspapers across the United States are remarkably homogenous in terms of their price. Audit Bureau of Circulations numbers from 2000 show that nearly all U.S. papers charge the same amount for their daily editions, and nearly the same amount for Sunday editions. The median cost of a daily paper has been $.50 since 1996, regardless of the size of the paper or its circulation. Average, or mean, costs tend to vary by circulation groups because a few newspapers charge slightly more or less for daily editions; for all newspapers, the mean cost is $.49. Sunday figures have been stable over the same period, with papers under 25,000 circulation charging a median amount of $1, papers between 25,000 and 50,000 charging $1.25, and papers over 50,000 circulation charging $1.50. The median charge for all Sunday papers is $1.25, and the mean charge is $1.28. Fully 76 percent of the 950 Audit Bureau of Circulations members that release single-copy costs charge 50 cents for their newspapers.

Newsprint Availability and Cost

The availability and price of newsprint remained relatively volatile through the late 1990s and early 2000s, with newspapers' desire to maintain a constant stock of paper colliding with supply constraints in the newsprint milling system. Prices per ton continued to fluctuate, reaching a high of $605 per ton in November of 1998 and falling as low as $470 per ton in September 1999. In 2000, newspapers used 11,983,000 metric tons of newsprint, a 1.1 percent increase over 1999. Stocks on hand remained relatively constant, with newspapers keeping an average of 43 days' supply on hand in 2001 and 2002.