Zambia

Basic Data

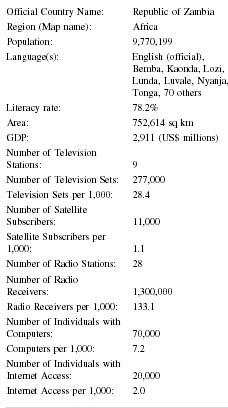

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Zambia |

| Region (Map name): | Africa |

| Population: | 9,770,199 |

| Language(s): | English (official),Bemba, Kaonda, Lozi,Lunda,Luvale,Nyanja,Tonga,70 others |

| Literacy rate: | 78.2% |

| Area: | 752,614 sq km |

| GDP: | 2,911 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 9 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 277,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 28.4 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 11,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000> | 1.1 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 28 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 1,300,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 133.1 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 70,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 7.2 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 20,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 2.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

Zambia, formerly Northern Rhodesia, is a land-locked Central African country that won its independence from Britain in 1964, at which time it changed its name from Northern Rhodesia to Zambia. It is bordered in the south by Zimbabwe (the two countries share the world-famous Victoria Falls), Botswana, and Namibia; in the west by Angola; in the north by the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire); on the northeast by Tanzania; on the east by Malawi; and on the southeast by Mozambique.

Literacy in Zambia is about 78 percent among the adult population, and primary education is free and compulsory. In 1995 there were more than 1.5 million children in 3,883 primary schools; 199,081 students in 480 secondary schools; 3,313 students in 12 technical and vocational schools; 4,669 students in 14 teacher training institutions; and 5,891 students in two universities. The average annual income is US$300.

Literacy affects newspaper readership. The more educated members of the population are more likely to read newspapers. Readership is also affected by the fact that when families need to decide whether to buy newspapers or food, they are more likely to opt for food, which is quite common in Third World countries such as Zambia.

Many people engage in subsistence farming, especially corn, cassava, and sorghum. There is also commercial farming, mostly by whites who run large farms that produce corn, sugarcane, tobacco, peanuts, and cotton. Another mainstay of the Zambian economy are minerals. In the 1960s, Zambia was regarded as the world's third largest producer of copper. Only the United States and the then-Union of Soviet Socialist Republics produced more copper than Zambia. The country is also a major producer of cobalt.

History

In its early years, what is Zambia today had no recorded history. People moved around freely, establishing settlements where they could under the rule of African chiefs. Today, Zambia boasts some 70 ethnic groups scattered over the sparsely populated country. Arabs and whites, mostly from Britain, also relocated to Zambia over the years. The Arabs came in as traders and merchants, while the whites were missionaries, civil servants, commercial farmers, miners, adventurers, and entrepreneurs. Over time, English became the official language used for business, government, commerce, and schooling. The other major languages are Bemba, Lozi, Tonga, and Nyanja.

The British South Africa Company ruled Northern Rhodesia from 1891 until 1923, The country's large mineral deposits were exploited at this time, boosting the country's white population and economic prospects. This mineral wealth in Zambia was one of the motivating factors in trying to form the Federation of Rhodesia (combining Southern and Northern Rhodesia) and Nyasaland (now Malawi). Under the federal structure, which came into being in 1953, despite vehement African opposition, the capital would be located in Salisbury (now Harare), the chief city in Southern Rhodesia. The federal legislature and the government would be in white-run Southern Rhodesia. Although whites were a miniscule minority in the Central African federation, they were the political majority in the federal government and federal Parliament. Release of these details galvanized African nationalist leaders in Zambia and Malawi to mobilize to stop the federal idea from being implemented. Opposition from African nationalists in Southern Rhodesia was there, but it was not as vocal or strident as in the two northern territories. Whites in Malawi and Zambia favored federation, as did their Southern Rhodesian counterparts, because it would augment their regional numbers and make it less likely that Zambia and Malawi could be turned over to the black majority.

Reluctantly, in 1962, the British government accepted Nyasaland's desire to opt out of the federation. At the local level, in 1948, two Africans were named to the Northern Rhodesian Legislative Council, which was the beginning of the recognition that blacks needed representation in the legislature. After negotiations among the Africans, the whites, and the British government, a new constitution was agreed upon. It came into effect in 1962 and, for the first time, it was agreed that Africans would form the majority in the new Legislative Council.

On December 31, 1963, just 10 years after its founding, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was declared dead. African nationalists had triumphed. After that, it was just a question of time before Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland would join most of the rest of Africa in the 1960s in winning majority rule and independence from European colonial rules. Less than a year after the federation's dissolution, Northern Rhodesia became the independent country of Zambia on October 24, 1964. The United National Independence Party (UNIP), successor to the banned Zambian African National Congress, won a majority of the seats under the new constitution. UNIP leader Kenneth David Kaunda became Zambia's democratically elected president. Soon, Kaunda and Zambia moved systematically to eliminate the opposition and turn the country into a one-party state, something that had become fashionable in Africa.

Beginning in 1969 and continuing until 1991, Kaunda and UNIP were repeatedly re-elected. Economic turndowns, corruption, drought, food shortages, and a general air of feeling that it was time for change ended Kaunda's and UNIP's 27-year grip on power in 1991. The Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), led by former labor union leader Frederick Chiluba, humiliated Kaunda and UNIP with an overwhelming electoral victory. Zambia's economy and infrastructure had also suffered from sabotage and bombings by Rhodesian and South African air force planes. Zambia's crime was that it had provided refugee camps, limited training facilities for guerrillas and exile headquarters for Rhodesian and South African groups that were seeking to overthrow white minority-dominated regimes in Salisbury and Pretoria.

In the December 2001 election, Chiluba's hand-picked successor, lawyer Levy Mwanawasa, narrowly squeaked to victory by winning 30 percent of the votes against several opposition candidates. The opposition parties claimed the election was marred by fraud, vote rigging, and the government's misuse of its powers. Despite the more liberalized conditions since the return of multiparty politics, the minister of Information and Broadcasting Services in Zambia still has much control over the country's broadcasting system.

Media History

All forms of media are shaped by political, economic, educational, and social conditions, but the media can help shape things as well. For example, Chiluba and the MMD trounced the ruling party and ousted Kaunda, the only leader Zambians had known in their first 27 years of independence, since Kaunda opened up the political process. One of the factors, a relatively new one at that, that helped defeat Kaunda and UNIP was the emergence of privately owned and relatively independent newspapers. The new media voices became partners with those forces that were struggling for democracy in Zambia.

The Zambia News Agency (ZANA) is the main provider of domestic news. It gathers and distributes news and information to the country's media and works with the Pan African News Agency (PANA), which collects and redistributes news from other African countries. ZANA has not had the resources and personnel to reach its potential as the country's domestic news agency.

In 2002 there were four newspapers in Zambia: the state-owned Zambia Daily Mail and the Times of Zambia ;

The Post , which is independent; and the UNIP-owned Sunday Times of Zambia . All are published in English and have circulations in the 25,000 to 50,000 range. Each paper also has taken advantage of technology by also publishing an online edition.

The Zambia Daily Mail started its life in 1960, when it was called the African Mail . In 1962 its name was changed to Central African Mail . This weekly paper was popular among blacks in the early 1960s because it was not afraid to publish stories that were critical of the federal government, the colonial government, and authorities in Northern and Southern Rhodesia. The paper was coowned by David Astor, then editor of the Sunday Observer in London, and Alexander Scott, a former Scottish doctor. In 1965 the new Kaunda government bought the Central African Mail . Two years later, it had become a semi-weekly called the Zambia Mail . In 1970 the Zambia Mail became the Zambia Daily Mail , a state-owned daily.

Its main rival was the Zambian Times , founded in 1962 by a South African named Hans Heinrich.

The Zambian Times started its life in Kitwe, one of the country's mining centers. Heinrich, however, soon sold the paper to a British firm called London and Rhodesia Mining, which owned other newspapers in the region.

Meanwhile, the Argus Company, another owner of newspapers in Central and Southern Africa, started the Northern News in Ndola, another mining community. This newspaper, however, was aimed at the white community; it included foreign news from Britain. When Argus chose to leave Zambia to concentrate on its South African business interests, it sold the Northern Times to London and Rhodesia Mining, which shut down the Zambian Times and renamed its new property the daily Times of Zambia . A white Rhodesian civil servant, Richard Hall, became editor of the Times of Zambia . Hall trained African editors and reporters to take over from him; in 1975 Kaunda's government took over the Times of Zambia and relocated its offices from Ndola to Lusaka, the national capital.

In addition to the Zambia Daily Mail and the Times of Zambia , other newspapers emerged. The Weekly Post became popular among those who disagreed with the Chiluba government; it regularly attacked the government, made fun of its leaders, and scrutinized its actions. It started doing to Chiluba and the MMD what Kaunda and UNIP had done to the MMD in the days before multi-party politics became a major political player. But the Weekly Post was not the only paper critical of the new government. The church-owned National Mirror and the privately owned Sun were also critical. They regularly ran stories and columns ridiculing the new government and its leaders, something that could not have happened during the Kaunda days.

The Daily Mail and the Times of Zambia did for Chiluba what they used to do for Kaunda: defend the government from attacks in the private media. They have remained pro-government publications, again projecting the viewpoint of the government of the day. They have refused to open up their pages to opposition's views. Although sometimes irritated by some of the coverage, the Chiluba government and its successor, the Mwanawasa government, were far more tolerant of criticism. They also eschewed censorship, even when the media published articles and photos that some consider of questionable taste. Ironically, some of the tactics that the MMD used to discredit the UNIP government were used against it. In the 1990s, the MMD published ads in the independent media attacking the UNIP government and its policies. Opposition parties used the same ad tactics against the MMD.

State-Press Relations

The media has not always had a happy existence in Zambia. As elsewhere in Africa, the earliest newspapers in what was then known as Northern Rhodesia were aimed at the small white community. Africans were ignored, except in so far as they could be depicted as criminals or in other negative ways. When African nationalists started agitating for change in the 1950s and continuing into the 1960s, they could not count on newspapers, radio, or television to tell their story. During federation days, the federal government controlled radio and television outlets, which were used to demonize black nationalists and to tout the views of the federal government. At independence, the Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation (ZNBC) came into being as a single-channel television outlet. It was loosely patterned after the British Broadcasting Corporation, meaning it was supposed to be autonomous, nonpartisan, and objective. In practice, ZNBC quickly followed in the path trodden by other broadcasting outlets in most African countries—it became a state-run institution that tended to report news only from the government's and ruling party's perspective. Opposition views were absent from ZNBC radio and television news. Kaunda and the ruling party saw the broadcast media as handmaidens of the government and UNIP, there to propagate and spread, uncritically, progovernment views and policies. In the Kaunda view, which was shared by many African leaders, opposition parties were enemies whose views should never be published or spread by the media.

The change from Kaunda and UNIP to Chiluba and the MMD was more than symbolic. It seemed to signal a major philosophical change. Kaunda thought the media had one purpose: to serve and propagate his policies and those of the ruling UNIP. Press freedom was an alien concept. At the beginning of UNIP rule, the print media was privately owned. Once in power, Kaunda changed all that. He effectively took over control of radio and television and started after the print media, arguing that the media's role was to transform society, in line with government policy. Over time, Kaunda appointed the head of the broadcasting facility. He also appointed, promoted, and fired the editors-in-chief at the Zambia Daily Mail and the Times of Zambia . Under those conditions, the print media could not afford to be critical of Kaunda, UNIP, or the government.

The MMD took a different stance by promising to restore and respect press freedom. The MMD promised to let journalists do their work without interference, and that those with the means would be able to own print and electronic media outlets. Those interested in starting private radio and television outlets were encouraged to apply for licenses. A Media Reform Committee was even established to chart the way forward. Among the commit-tee's recommendations were privatizing the Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation, privatizing newspapers, and putting a freedom of the press clause in the Zambian constitution. The print media took advantage of the new freedoms. They criticized the new government and its president, made efforts to be a public watchdog, and tried to hold the government accountable for its actions. There were virtually no restrictions about what the media could not do or publish—a far cry from the autocratic Kaunda days.

Broadcast Media

Even though ZNBC depended on annual license fees to be paid by all television and radio owners and government subsidies, the government co-opted ZNBC for use as a state propaganda unit. In 2002 ZNBC remains the country's sole television broadcaster and is still seen, despite the change in government from UNIP to the supposedly press-freedom-committed MMD, as a state broadcaster. ZNBC also runs three government-oriented radio stations: Radio 1, which is multilingual and can be heard in Zambia's major languages; Radio 2, which is an English language service; and Radio 4. There are also two church-owned stations, Radio Icengelo and Yatsani Radio, and privately owned Radio Choice. This is unusual because many African countries do not allow privately owned radio stations, preferring instead to leave broadcast matters in the hands of state-owned outlets for propagating government policies and government programs.

Francis P. Kasoma, a former Zambian print journalist and now a professor in the department of communication at the University of Zambia, started broadcasting in Zambia in 1941 when the British colonial authorities initiated an African radio service. Twenty years later, in 1961, television arrived in the country, courtesy of the privately owned London Rhodesia Company. It was designed to serve the interests of the white community. At independence, the Zambian government purchased the television station, and it became part of ZNBC. From then on, ZNBC became an integral part of the Zambian government's propaganda machinery. ZNBC dutifully parroted government policies, repeatedly featured UNIP leaders and ignored opposition parties and leaders, except to denigrate them. According to Kasoma, Kaunda became a fixture on ZNBC news, regardless of what he was doing. His speeches, even at political rallies, were repeatedly shown on television, often uncut and unedited. Some of those speeches were repeated a number of times during the broadcast cycle. As president, Kaunda could and did appoint and fire the ZNBC director-general, the person with the responsibility for the daily programming.

Opposition ads were not allowed on radio or television, until the opposition successfully sued for the right to have its election ads screened, even though it had to pay for them. While the MMD went to court to force ZNBC to screen its paid ads, Kaunda and UNIP enjoyed unlimited access to the airwaves, including during peak viewing and listening hours. The government and the ruling party did not pay for those ads. ZNBC actually carried an announcement saying it was airing the ads to comply with the court decision. The Press Association of Zambia also went to court to seek the temporary removal of Steven Moyo, then the ZNBC director-general, on the grounds that he was too pro-government and anti-MMD. Although Moyo was temporarily removed, broadcast news rarely covered the election fairly. Stories about the MMD were few or biased.

Despite all this help from the media, Kaunda was still defeated; under the MMD and Chiluba, ZNBC television and radio programs were opened up to government and opposition parties, including UNIP. Opposition parties and candidates now had access to the airwaves in this changed political culture. Programs critical of the government of the day were no longer automatically banned. No longer were radio and television programs dominated by the theory that what the president did or said should be the top story of the day, regardless of its insignificance, although the government still carried an unfair advantage over other broadcast media players.

While MMD continued government control of ZNBC as a state broadcaster, it did open up the airwaves to other voices, though in a limited context. By 1994, for example, the government announced that those interested in starting private radio and television stations could apply for licenses. Some FM and medium wave frequencies were made available for radio, while a few UHF bands were also made available for television broadcasting. Despite these changes, however, the MMD government was adamant that under the Broadcast Act no broadcast licenses would be granted to political parties.

The number of radio receivers in Zambia grew from 760,000 in 1994 to 1,000,000 in 1996. The number of actual listeners is much higher than that because of large numbers of family members who gather around each radio set, plus those who listen to broadcasts in beer halls and other community gathering centers. Radio also attracts more Zambians because it is not affected by literacy and requires no active participation by audiences who can be engaged in other activities while still being able to listen and hear the messages, music, advice, and call-in programs. Radio broadcasts in English and a variety of African languages. Television has grown more slowly, rising from 245,000 receivers in 1994 to 270,000 in 1996. Its broadcasts are also in English and some African languages. There are nine television broadcasting stations.

Electronic News Media

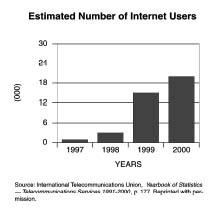

Although far from being totally free, the media in Zambia has been far freer than it was in the 27 years from independence in 1964 to the 1991 electoral defeat of Kaunda and his UNIP. Zambians now have access to competing and opposing voices. The private press has taken upon itself the role of public watchdog and defender of freedom and the truth. Access to the media has improved markedly. Criticism of the government is no longer a crime. However, despite these newfound freedoms, access to the media remains limited because of illiteracy, poverty, inability to afford newspapers, and the costs of radio and television. Moreover, the lack of electricity has kept the electronic media out of the reach of a majority of Zambia's citizens. The Information Revolution has made the Internet available in Zambia. Poverty, however, has militated against making e-mail and other Internet services available to most Zambians. Computers, simply, are too expensive. Internet sites and cafes are available, but most Zambians cannot afford to log on and off. Many prefer to spend their limited cash on more pressing needs, such as food.

Bibliography

"Africa." Encyclopedia of the Nations , 7th edition. World Mark Press, 1988.

Africa South of the Sahara , 31st edition. Europa Publications, 2002.

International Yearbook (The Encyclopedia of the Newspaper Industry) , 82nd edition. n.p., 2002.

Kasoma, Francis P. "Press Freedom in Zambia." In Press Freedom and Communication in Africa , eds. Festus Eribe and William Jong-Ebot. Trenton, N J: Africa World Press Inc., 1997.

Merrill, John C., ed. Global Journalism (Survey of International Communication) , 2nd edition. New York & London: Longman, 1991.

Tendayi S. Kumbula

keep up with such great work