Singapore

Basic Data

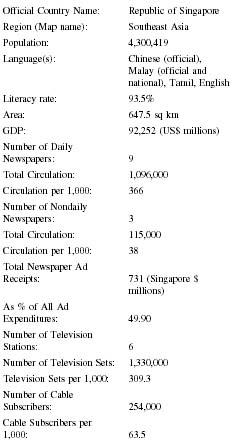

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Singapore |

| Region (Map name): | Southeast Asia |

| Population: | 4,300,419 |

| Language(s): | Chinese (official), Malay (official and national), Tamil, English |

| Literacy rate: | 93.5% |

| Area: | 647.5 sq km |

| GDP: | 92,252 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 9 |

| Total Circulation: | 1,096,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 366 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 3 |

| Total Circulation: | 115,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 38 |

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 731 (Singapore $ millions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 49.90 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 6 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 1,330,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 309.3 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 254,000 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 63.5 |

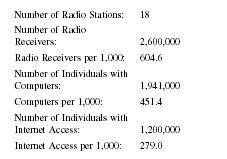

| Number of Radio Stations: | 18 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 2,600,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 604.6 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 1,941,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 451.4 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 1,200,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 279.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

The Republic of Singapore consists of a 240-square-mile island and several other surrounding smaller ones located in Southeast Asia. The main island (whose territory also includes some land reclaimed from the sea) is connected to Johor, the southernmost state of peninsular Malaysia, by a causeway. Close by and directly south are the many islands that make up the Republic of Indonesia. Singapore is a multiethnic, cosmopolitan state with a population consisting overwhelmingly of Chinese (77 percent), followed by Malays (15 percent) and Indians (6 percent); Eurasians and others constitute the rest. Singapore is city-state with a highly concentrated urbanized population and no rural areas or peasant population to speak of. Most Singaporeans live in government controlled, though individually owned, apartments (through the Housing and Development Board, a statutory agency) in multi-story high rise buildings that dot the urban landscape.

Singapore originated as a small Malay fishing village that belonged to the Sultan of Johor. A British colonialist, Stamford Raffles, purchased it on behalf of the East India Company and began the course of its contemporary development. Raffles saw potential for setting up a trading post on the island given Singapore's deep, natural harbor. Following increased immigration (primarily from China, and India) and the expansion of trade, Singapore became a Crown Colony, administered directly by the British government. It was occupied briefly by the Japanese following the surrender of British forces in Southeast Asia during World War II. After the British returned there were increasing calls for local self-government. In 1959, an elected government led by the People's Action Party (PAP) and its leader, Lee Kuan Yew, achieved internal power, although external affairs and defense continued to rest with the British Government. Singapore joined the newly formed Federation of Malaysia in 1963 along with former British colonies Sabah and Sarawak on the island of Borneo. After a brief and rocky association it left the Federation in 1965 through a mutual agreement to become an independent country.

The emergence of Singapore from an obscure Southeast Asian island dependent on entrepot trade derived from its neighbors (primarily, Malaysia and Indonesia) to an internationally known hub for the global economy in the short span of three decades has been nothing short of spectacular. Geoffrey Murray and Audrey Perera in their book, Singapore: The Global City-State trace what is often described as Singapore's economic miracle to "a five pronged policy—free trade, high savings, full employment and an equitable wage policy, a foreign-investment friendly environment and a development-oriented government." Beginning with rapid industrialization in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Singapore successfully moved its infrastructure and population into various highly skilled business and financial services, the high technology, as well as information technology sectors of the international economy; the hallmarks, arguably, of a flourishing post-industrial economy. Its major trading partners range from all over the world and are led by the United States, followed by Japan, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Thailand, Australia and Germany. Singapore is therefore almost always classified in international economic and human development rankings as having achieved the status of an affluent developed country (e.g., per capita gross national product for the year 2000 is estimated at US$21,828).

Singapore has four official languages, namely English, Mandarin Chinese, Malay and Tamil. These principal languages are used in all governmental communication with members of the public, imprinted on national currency, taught in government-run or recognized primary and secondary schools, and allowed to be used in radio and television broadcasts. However, English is predominant in all legislative, bureaucratic and judicial matters, tertiary education institutions, and major commercial transactions. It is considered the language of national integration. English is spoken by 20.3 percent of the population and even more widely understood; Mandarin is spoken by 26 percent while 36.7 percent are conversant in other Chinese dialects (e.g., Hokkien, Cantonese etc). The linguistic minorities consist of 13.4 percent of the population who speak Malay and 2.9 percent who speak Tamil. In school, following an official policy of bilingualism, all students are required to study and take public examinations that include tests in English and their respective mother tongues. Although the Chinese speak many dialects, and Indians different languages, it is assumed that the "mother tongues" they will be learning in school are Mandarin Chinese and Tamil, respectively.

Modern Press

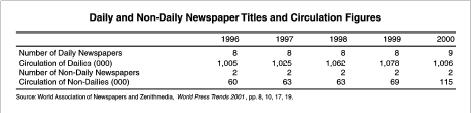

Given its high rates of affluence and literacy, it is no surprise that Singapore has had and continues to enjoy equally high rates of newspaper readership for its technically well laid out and attractive newspapers. It is estimated that in 1998, total newspaper circulation stood at 1,056,000. The press in Singapore publishes in all four of its official languages. The English press has captured almost half (49.1 percent) of the total circulation, with Chinese newspapers (43.9 percent) following closely behind. Malay (6.2 percent) and Tamil (0.8 percent) newspapers rank far below. The most important players in the Singapore press scene are therefore, the English and Chinese newspapers. The major newspapers and their 1998 circulations in rank order are as follows: The Straits Times , an English daily morning newspaper that was founded in 1845, had a circulation of 369,773. The Lianhe Zaobao (United Morning News), a Chinese morning daily with a circulation of 202,063 and its afternoon counterpart the Lianhe Wamboa (United Evening News) with a circulation of 129,715, are next in rank order. Both of these newspapers were established in 1983 as a result of the government-influenced merger of two other competing older Chinese newspapers (the Nanyang Siang Pau and the Sin Chew Jit Poh ). In fourth place is a slightly older (established in 1967) Chinese newspaper, the Shin Min Daily , an afternoon newspaper with a circulation of 112,497. Fifth is an afternoon English daily established in 1988, The New Paper , with a circulation of 107,080. Other smaller published newspapers include a Malay morning daily, Berita Harian (1957; Daily News), a trade and commerce-oriented English daily, Business Times , and a Tamil morning daily, Tamil Murasu (1935; Tamil Herald). A recent entrant is the English morning newspaper Today , which is said to be distributed to nearly 100,000 homes and offices, and as far as can be determined, free of charge. It provides shorter and pithier articles for individual readers whose busy schedules presumably make it difficult for them to peruse weightier newspapers leisurely.

As may be expected, the Sunday editions of all of the newspapers mentioned above generally enjoy somewhat higher circulation numbers than their daily counterparts.

In general, the morning newspapers are thought to constitute the elite or quality press. Newspapers published in the afternoon are more popular or sensation-oriented, catering less to long-term subscribers and more to those buying on a whim. However, in the Singaporean context, sensationalism (primarily using large, bold headlines and photographs combined with news and features that focus on sports, movies, personalities, "human interest," and sex) has a much tamer and more restrictive definition in comparison to similarly oriented publications in Japan, India or the West.

Economic Framework

Until the early 2000s all of the local daily newspapers that circulated on the island of Singapore were owned and operated by one entity, the publicly owned Singapore Press Holdings (SPH). While the company's stocks are publicly traded, there are two types of shares whose monetary value is similar: ordinary and management shares. SPH monopolizes the daily newspaper market with a combined circulation of more than one million copies in the various languages, morning and afternoon. SPH also publishes several periodicals such as Home and Decor (English; focuses on home design and interior decoration), Her World (English; intended for women) and You Weekly (Chinese; entertainment, lifestyle and television). In addition, it has diversified and become involved in other businesses: these include other communication-related areas such as cable television, cellular phone and Internet services, as well as in other sectors such as commercial real estate property investments. Eddie Kuo and Peng Hwa Ang declare that SPH is a highly profitable company that employs 3,000 workers. If SPH's publication patterns are examined closely, it will be noticed that with minor exceptions, newspapers in their stable do not necessarily compete with each other in terms of language of publication and time of day. The sole exception to this is the competition in the afternoon for Chinese readers between the Lianhe Wambao and the Shin Min .

In an effort to provide a modicum of competition to various publications belonging to the SPH, the government has licensed the entry of a newspaper ( Today ) from the newly formed Media Corporation of Singapore (MCS). This corporation is the result of the conversion of Singapore's previously government-owned organization (originally formed as a government department) that runs all of its television channels and radio stations into a private corporation. Both groups will continue to retain their near monopoly over their core businesses (print publications for SPH and broadcast outlets in the case of MCS). However, in return for facing the new competition in the newspaper sector, SPH is being allowed to own and operate two direct to air television channels and two radio stations. Both companies were also expected to expand their presence on the Internet and into multimedia content delivery. It is assumed that the resulting competition between the two groups in the various forms of mass communication will be beneficial in two ways. First, it would help raise the overall quality of locally produced content and second, ensure that Singaporeans continue to retain their preference for news, features and other content that focuses on their immediate environment as delivered to them by locally owned organizations.

In 2002, the Minister of Information, Communications and the Arts announced that a new agency, the Media Development Authority (MDA) would supervise all forms of media operating in Singapore, including newspapers. In addition to helping develop local media content and encouraging investment, the MDA would ensure that communication outlets pay attention to the twin national goals of maintaining social harmony and furthering economic growth. Further, this agency will help enhance competition between, and the maintenance of quality by, the two major media groups, the SPH and the MCS.

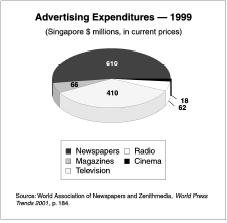

Similar to newspapers in other countries, the bulk of newspaper earnings in Singapore come from advertising and not from the sale of papers either individually or by subscription. Unlike other countries, however, newspapers in the republic continue to dominate other media in terms of advertising revenue earnings. This can be contrasted to the experience of countries such as the US, where over time, television in its various forms surged to become the main forum by which advertisers reach consumers. It is estimated that half the total advertising dollars (US $689 million in 1998) spent in Singapore are for advertising in newspapers, as opposed to slightly more than a third for television advertising. Until recently advertising in The Straits Times , the English newspaper of record, was so popular that it found itself in the enviable position of turning away advertisers for lack of space in its daily and Sunday editions. Other forms of media (radio, magazines, and movies) typically score percentages of advertising dollars in the single digits.

The distribution of newspapers in Singapore is carried out by both traditional and contemporary means. Traditional means include the extensive use of vendors (these are usually contractors, although attempts are being made to convert them to employee status) who distribute newspapers to home subscribers in specified territories. Reputedly, some of these areas were demarcated in the past with the help of criminal gangs or secret societies. Typically, a vendor would distribute around 1,000 copies of all newspapers belonging to SPH to homes in the multistory apartment buildings of a given area. This is complemented by sales at newsstands, mainly for impulse buyers (there is overlap between these two methods, i.e., vendors may be associated with running a particular newsstand). This existing network has been supplemented by more contemporary means of distributing newspapers that include selling them at gasoline filling stations, neighborhood convenience stores, supermarkets, and pharmacies. Interestingly, SPH has also experimented with selling newspapers using solar powered vending machines in the busier parts of Singapore.

Press Laws

The press in Singapore, in addition to functioning on the basis of the expectation that it help foster national interests as defined by the government, is also under the latter's strict supervision, as it has to operate within a number of legal constraints. The principal and most comprehensive piece of legislation that affects print publications is the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act (1974) or NPPA. This legislation (derived from the colonial Printing Presses Act of 1920) allows the Singapore government to wield a three-pronged strategy in controlling the press, its ownership, personnel and ultimately, published content. First, it requires that all publications (local and foreign), printers, and the primary personnel associated with those publications, to be registered with and licensed by the government and to have those permits renewed every year. Thus, it would not be difficult for the government to deny licenses to particular individuals or groups, or to refuse to renew permits for those publications that were deemed to have overstepped their bounds in terms of critical or offensive content. Second, any given individual or group can only own three percent or less of the total stock of a newspaper company. This was a way of breaking up the family-owned newspapers that had existed earlier and ensuring that such concentrations of ownership does not return. Third, the NPPA envisages two types of shareholders. Only persons approved by the government are allowed to buy what are referred to as "management shares" while others may buy ordinary shares. The difference between the two is in terms of voting power, specifically on editorial policy and personnel decisions. Each "management share" vote is worth two hundred times the vote of an ordinary share. By possessing the power of approval over who may own or buy these "management shares" the Singapore government indirectly exercises control and direction over those allowed to have a say in the editorial governance of all local newspapers and magazines.

A 1986 amendment to the NPPA allows the government's Ministry of Communication to reduce the number of copies circulated in Singapore of any foreign publication that was labeled as engaging in domestic politics. This gives the government broad latitude in terms of reducing the availability of a particular publication within the republic without seeming to suppress or eliminate it completely. It is also an effective mechanism for hitting a publication where it hurts, its circulation figures and consequently, its advertising revenues. Over the years several international and regional newsweeklies such as Time, Asian Wall Street Journal, The Economist, Far Eastern Economic Review , and the now defunct Asiaweek , have fallen victim to this provision of the NPPA. Typically, the charge of interfering in domestic politics followed that publication's critical coverage of the government's political actions (e.g., alleged unfair treatment of the miniscule opposition parties or its members) or business news defined as negative. This usually went along with the refusal or reluctance of the concerned publication to publish letters on the disputed matter from government officials in their entirety and without editing. In some instances, following conciliatory actions, the circulations of some affected publications were partially or completely restored. Although not enforced in every case, foreign publications are also required to post a bond of nearly $500,000 (Singapore) "in case of future journalistic indiscretions."

In addition to specific laws that deal with libel and defamation (over the years, many Singapore leaders have gone to court on these grounds and won several judgments and large financial damages against publications and journalists) and copyright infringement, there are a few other important laws that affects press operations. One is the Undesirable Publications Act that prohibits the sale, importation or dissemination of foreign publications defined as contrary to the public interest. Although broadly defined, the specific targets of this law have often been publications construed as publishing obscene, pornographic material or seen as advocating alternative sexual lifestyles. An earlier piece of legislation from before Singapore's independence, the Internal Security Act, has rarely been used against the press in recent times; however,

In addition to these legal weapons, it should be understood that the likelihood of winning cases in court in which the government is the opposing party is generally slim in Singapore. As a result, it is fair to say that local newspapers have adapted themselves to their specified functions of providing education and information within the existing setup in Singapore. They are therefore, not likely to challenge continuing restrictions on the basis of the need for greater freedom of the press. Foreign publications that may do so face consequences such as suffering circulation cuts that that are almost equivalent to an outright ban and strictures on the entry and work of their correspondents. Consequently, some foreign publications have withdrawn from active, continuous coverage of Singapore.

Censorship

It is important to note that censorship in its most blatant form, prior screening of the content of publications by a designated government or statutory agency, does not exist in Singapore, although radio, television and movies have historically been subject to such censorship. However, as noted earlier, the government exerts a variety of means of control over newspaper personnel, functioning and distribution. These include, among others, official

Two additional factors need to be taken into account. First, surveys of Singaporeans have shown repeatedly that a large majority is happy with the current content and coverage of their country by the local press, and do not necessarily want aggressive, combative or crusading journalism. Next, the government alone is seen (by both journalists and ruling politicians alike) as having the right to set the national agenda and priorities, by virtue of having won elections and repeatedly received a mandate for its policies from the people.

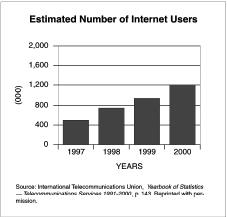

A relatively new, though important, anti-censorship force is the rise of the Internet and electronic communication. Singapore became the second country (after Malaysia) in Asia to provide Internet service access to its citizens in mid-1994 and subscriptions are said to have grown to around 670,000 users in mid-1999. The major newspapers belonging to SPH have developed their own separate news-oriented websites, partly in response to reports that newspaper readership among those below 30 is declining. Singapore's officially expressed desire to move forward to become a wired, knowledge-based economy or what is often called an "intelligent island" drives the dilemma faced by those who may wish to restrict the flow of "undesirable" information and content from elsewhere. This means that unlike earlier times and with other media, given the global structure, libertarian culture and democratic ethos of the Internet, censorship would be difficult, if not impossible. While official guidelines and filtering systems are in place, Singapore's leaders have begun to acknowledge that education of, and self-regulation by, the individual subscriber may be the only answer to this dilemma. Already, government officials have begun discussing the difficulties of formulating and deploying top down, stringent controls over the far-flung and variegated information and education sources that characterize the information age. For example, they have decided to review the ban on satellite dishes which are currently available only to foreign embassies, financial institutions and other selected agencies and not to the public. This ban is particularly ironic in that several regional satellite television companies have located themselves in Singapore, but can only broadcast to other countries. They have also made suggestions that, unlike the past, attempting to block the publication of what it does not like by targeting a particular newspaper or magazine may not be productive. Instead, government may be better served by insisting strenuously to the newspaper or other content provider that the former's views and versions of events be also carried and given equal weight. Under this scenario, the newspaper subscriber reads and learns the facts and arguments from both viewpoints and decides on his or her own what to believe.

State-Press Relations

Politically, the government continues to be dominated by the People's Action Party (PAP), which has won every election since independence, and which generally espouses highly interventionist governmental policies and an iron grip over various spheres of Singapore's social and cultural life (including mass communication media). In its earlier days, the party campaigned as a socialist entity. However, in the 1970s and later, it generally abandoned socialism in order to embrace "free trade" and to spur investments by foreign multinational corporations. Although the PAP's proportionate share of total votes cast in regularly held elections has declined somewhat (the high point being 76 percent in 1980) it has generally enjoyed supermajorities in Parliament, usually holding 90 to 100 percent of the seats. During election campaigns, it is not uncommon for the PAP to suggest or state that given the impossibility of the small opposition coming to power, constituencies that elected members of the latter would not be allotted government funded improvements. Critics have also decried the PAP and its leaders for their authoritarian and paternalistic tendencies. However, unlike many other developing countries dominated or controlled by a single party, the PAP's governance of Singapore has also earned kudos and respect for its stability, farsightedness, efficiency, competence, and the general absence of corruption.

For more than three decades, the PAP-led government of Singapore has played an active role in controlling and directing the mass communication media of the country by making sure that they did not become focal points for criticism and opposition. Radio and television in the early years of Singapore's independence were already under direct government control, although newspapers were privately owned (often by families). Two English language daily newspapers, Eastern Sun (accused of being backed by Communists) and Singapore Herald (accused of being overly critical of various government policies such as compulsory national service) were closed down. Personnel associated with the Chinese language daily Nanyang Siang Pau were detained for stirring up racial prejudice. Later, pressure was brought to bear on local newspapers against covering or publicizing the tiny opposition parties and their leaders. Some newspapers were required to merge, and some to cease publication while new ones were created. Foreign publications regarded as meddling in local politics were targeted for reductions in circulation, sued for libel and their correspondents not given work visas. The general approach to the press by the Singapore government can be seen to embody features of what many observers characterize as its customary and unapologetic "soft authoritarianism" on all sectors of, and matters pertaining to, the republic. To justify such an approach, Singaporeans are often reminded of riots and disturbances that took place in the past as a result of alleged adverse or chauvinistic newspaper coverage and interpretation of inter-ethnic matters.

In recent times, several Singaporean leaders and intellectuals have attempted to articulate a formal rationale for the continued existence of strict political control and legal constraints over constitutionally guaranteed freedoms of association, assembly, speech and expression. Allowing members of the public and the press the unfettered exercise of these rights, they have argued, is inimical to the interests of maintaining order in a highly sensitive multiethnic Singaporean society that possesses only a fragile and recently acquired sense of nationhood. In particular, they have proposed that in contrast to the highly individualistic Western democracies that are the source of these "individualistic" ideas, Singapore needs to be guided by "Asian values," defined by Michael Haas as: "(1) community before self, (2) the family as the basic unit of society, (3) consensus rather than competition to resolve conflicts, (4) racial and religious tolerance and harmony, and (5) community support for the individual." Members of Singapore's ruling elite often use these identified values (said to be derived from Confucianism and also shared by other Asian cultures) to distance Singaporean society from the "decadence" of, and to proclaim its superiority to, the West, where these values do not hold sway. Thus, open and forceful criticism of the government as well as any portrayal of its members in a negative light are seen as luxuries that Singapore (and, by implication, other Asian societies) cannot afford to indulge in. This not only because these pursuits fritter away energies better spent fostering government-led economic development, but also because such criticism violates the important values of consensus, harmony, and communitarianism. However, critics are quick to point out that these arguments are clearly self-serving for those in power and serve more to reinforce the existing status quo. The constant harping on Asian values and the denigration of individual rights and freedoms is used, according to Haas, to "persuade the public that any deviation from PAP rule would bring economic disaster to Singapore," and for "telling the people what to think."

Singapore media are regularly placed by Freedom House's annual international rankings of press freedom in the category "not free." For the republic's media, the concept of Asian values, as promoted by the government translates as follows. The press and other communication outlets are expected to function as responsible team players putting national and governmental interests over the freedom to disseminate anything and everything that they may wish to publish or broadcast. In contrast to the Western notion of the press as an active watchdog over the government and its officials, in Singapore its pro-government role is to faithfully communicate national plans, priorities and pronouncements to the public and "to promote numerous campaigns, initiated and managed by the government." Thus, casual visitors to the country are likely to be struck by the notable absence of political controversy, criticism and bickering in the pages of Singapore's newspapers, and their uniform toeing of the governmental line in terms of viewpoints on almost all national and international issues.

Broadcast Media

For a variety of reasons, the broadcast media (radio and television) have historically been under government control in Singapore. In 1994, the government's broadcast holdings were spun off as a corporation, Singapore International Media, whose name was changed in 1999 to Media Corporation of Singapore (MCS). As noted previously, MCS has recently entered the newspaper market to compete with SPH, which previously monopolized this sector. MCS currently runs four core direct-to-air television stations (broadcasting programs in the four official languages), a regional news channel (Channel News Asia), a teletext service, an outdoor television channel for commuters and public areas, and is in the process of introducing digital broadcasting. In terms of its radio holdings, it controls 11 core stations (programming in all official languages), another that broadcasts specifically to certain groups within Singapore's expatriate population (Japanese, German, and French programming) and a foreign service, Radio Singapore International. Further, it is expanding into digital audio broadcasting. The earlier broadcasting monopoly of MCS is also being challenged by the entry of SPH into the television market in 2001 with two news channels in English and Chinese.

Summary

The press in Singapore has a history that is more than 150 years old. Similar to the republic's population, it is both modern and efficient in its setup, operations, and layout. At the same time, it continues to be subject to strict government policies and legal restraints that have served to constrain it in the interests of national development and communal harmony. Given the expansion of sources and options for Singaporeans to be informed, educated, and entertained, today, the press can be characterized accurately as being in the throes of transition and change. This change process encompasses both Singapore's media (e.g., managed competition between multimedia companies that were previously protected sectoral monopolies) and its government (e.g., rethinking of official policies designed historically to curb the flow of "undesirable" information).

Bibliography

Haas, Michael, ed. The Singapore Puzzle . Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1999.

Kuo, Eddie C. Y. "The role of the media in the management of ethnic relations." In Goonasekera, Anura and Youichi Ito, eds., Mass Media and Cultural Identity: Ethnic Reporting in Asia . London: Pluto Press, 1999.

Kuo, Eddie C. Y., and Peng Hwa Ang. "Singapore" Pp. 402-428 In Gunaratne, Shelton A., ed. Handbook of the Media in Asia . New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2000.

Murray, Geoffrey, and Audrey Perera. Singapore: The Global City-State . New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996.

N. Prabha Unnithan

Further, I'm flying back to Singapore at the end of May 2019, because my daughters birthday is in June. She'll be 2 years old, so I don't want to be turned away again once I arrive. Please lead me in the right direction for help.

Thanks

Gary Thelen