Slovakia

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Slovak Republic |

| Region (Map name): | Europe |

| Population: | 5,414,937 |

| Language(s): | Slovak (official),Hungarian |

| Literacy rate: | 100% |

| Area: | 48,845 sq km |

| GDP: | 19,121 (US$ millions) |

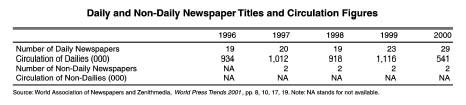

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 29 |

| Total Circulation: | 541,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 126 |

| Number of Nondaily Newspapers: | 2 |

| Total Circulation: | 6,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 2 |

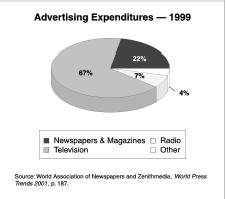

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 11.00 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 38 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 2,620,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 483.8 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 754,380 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 139.7 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 620,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 114.5 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 95 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 3,120,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 576.2 |

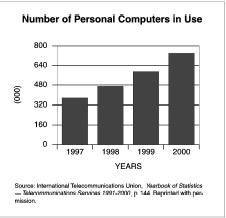

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 740,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 136.7 |

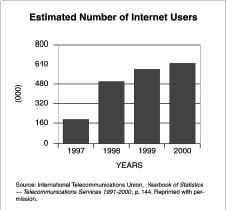

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 650,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 120.0 |

Background & General Characteristics

A member of the European Union, Slovakia— officially the Slovak Republic—broke from Czechoslovakia in 1993 to become an independent republic. Originally settled by Illyrian, Celtic, and Germanic peoples, Slovakia was part of Great Moravia in the ninth century, then Hungary in the eleventh century. After World War I, the Slovaks joined the Czechs of Bohemia, forming the Republic of Czechoslovakia in 1918. Under Communism from 1948, Czechoslovakia moved toward democracy through the 1989 "Velvet Revolution," when the Communist government resigned.

The Slovak Republic's population of 5.4 million is a diverse mix of Eastern European ethnicities; 86 percent Slovak, 11 percent Hungarian, with Gypsy, Czech, Moravian, Silesian, Ruthenian, German, Polish, and Ukrainian minorities making up the remaining 3 percent. Religion is predominantly Roman Catholic (60 percent), with many people speaking both Slovak and Hungarian. Education is compulsory from age 6 to 14, and the country enjoys a 100 percent literacy rate. Slovakia's landlocked terrain features rugged mountains in the central and northern part with lowlands in the south; 57 percent of its inhabitants are city dwellers.

After the fall of Communism, Slovakia's media has struggled to transform from a restrictive state-controlled climate to a dual system of public, state media and diverse, independent publications and broadcasting. Soon after independence, private broadcast venues were launched alongside a cornucopia of special-interest newspapers and magazines. In the twenty-first century, Slovak media—with a large, educated audience and little commercial capital—continues to be an attractive market for foreign interests and new technology media. Yet an oppressive environment was instigated by the regime of Prime Minister Vladimír Mećiar from 1992 to 1998.

Press freedom improved dramatically after 1998 elections replaced Mećiar and his Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS) with Prime Minister Mikuláś Dzurinda of the Slovak Democratic Coalition (SDK). Mećiar, who served three times as prime minister, battled with President Michal Kováć over executive and government powers, opposed direct presidential elections, resisted economic liberalization, and disregarded the rule of law and a free press, bullying state-run media outlets into pro-government coverage.

Under the new coalition government of Dzurinda, Parliament dismissed the directors of state-supported Slovak broadcast outlets for failure to guarantee objectivity. Since 1999 there have been no reports of government interference. A parliamentary democracy, Slovakia elected President Rudolf Schuster by a 57 percent popular vote in 1999.

The social and political changes brought about by the Slovak independence and the fall of Communism resulted in large increases in the number and diversity of print publications. Since 1989 the number of periodicals tripled—from 326 to the 1,034 recorded in 1998. The majority of Slovakian national newspapers are broadsheet, publishing detailed information on a wide range of news and current affairs. Though most strive for objectivity, each tends to express strong opinion for or against the government, or a certain party or policy in its editorial columns. Weekend editions include colorful special sections with features on sports, economics, finance, technology, travel, style, and analysis.

The highest-selling daily is the Novy Cas (The New Times), with a circulation of 230,000. The tabloid is read by two-thirds of the population under 45, and women make up over half its readership. Slovakia's second largest paper is Pravda (Truth), once the Communist Party's mouthpiece. Its readership is primarily older urban residents. Praca (Labor) is the trade unions' paper, largely distributed in the West Slovak region. Two competing dailies— Sme and Slovenska Republika —attract a similar share of Slovak readers. Other dailies include Sport and Uj Szo .

With 365 regional and local periodicals, most Slovak towns and cities have their own regional and local newspapers—4 daily morning papers, 4 evening papers, 94 regional papers, 167 municipal and local papers, 72 in-house papers, and 37 consumer publications. Covering local, national, and international news, these papers provide a significant audience for local advertising. In addition, businesses, societies, public bodies, and universities publish specialty publications.

Slovak magazines and periodicals include over 560 titles with a circulation of at least 17.2 million. Since 1989 the number of titles in this market has increased 168 percent, with at least half as much in circulation. Slovenka , the highest-circulation weekly magazine at 230,000 copies, leads the market of some 17 women's periodicals in Slovakia with an aggregate circulation of 1.2 million. Opinion journals include Nedel'na Pravda and Plus 7 dni , both weeklies reviewing social issues, politics arts, and literature, as well as Trend , a weekly focusing on economics. The number of church and religious periodicals has nearly tripled since 1989; Katolicke Noviny is among Slovakia's top 10 magazines, with a circulation of 100,000 and a readership of 300,000.

Bravo leads the list of some 34 youth publications, with a circulation of 90,000 covering pop music and other teen interests, while at least 235 scientific and professional journals count an aggregate circulation in excess of 1 million. Over 46 free advertising papers are distributed to some 3.5 million Slovaks weekly. Over 40 newspapers

Economic Framework

The reintroduction of a post-Communist, free market economy has been a long and difficult process in Slovakia. Before 1989 many Slovak industries were inefficient and not competitive in the world market. The foreign investment needed to modernize these industries has been elusive because of the country's erstwhile political instability. However, direct foreign investment totaled $1.5 billion in 2000.

The Slovak economy has improved since the country's 1993 independence. From 1993 to 1994, the Gross Domestic Product grew 4.3 percent, and inflation fell from 20 percent to 12 percent. Foreign trade is important to Slovakia's economy; in 1994 imports and exports each totaled about $6 billion. Over 50 percent of its trade is with European Union countries, and Germany is Slovakia's largest trading partner, followed by the Czech Republic, Austria, Russia, and Italy. Imports include natural gas, oil, machinery, and transportation equipment, while exports include machinery, fuels, weapons, chemicals, and steel.

Slovak press distribution is privately controlled. However, secondary government influence is present in Danubiapress, the nation's largest private company with links to the political party, HZDS. In 1998 a government agency distributing 30 dailies and 650 magazines sold 97 percent of its shares to Danubiapress, despite protests by Slovak journalists' organizations.

Press Laws

Since its 1993 formation, the Slovak Republic has made a steady, if indirect, advance toward a free press. Print media are uncensored, exhibiting a wide variety of opinions. Slovakia's Constitution provides for freedom of the press. Media are subject to the 1966 Law on Mass Media Communications, which was amended in 1990. Individuals may freely criticize the government without fear of reprisal, and threats against journalists are rare. Constitutional provisions include a limitation on press freedom only to necessitate freedoms of others, state security, law and order, health, and morality; and the government must provide reasonable access to documents and information. In addition, the state's legislation includes the Charter on the Human Rights and Freedoms, based on the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

Slovakia's Law on Public Information Media regulates the rights and obligations of the media operators and their relations to government authorities, local self-governing bodies, public institutions, and individuals. To discourage cross-ownership and media monopoly, the bill restricts owners of national media outlets—dailies, national radio, or television—to 20 percent capital share in other media.

The Council of the Slovak Government regulates information policy and media legislation for Mass Media, an advisory group, which prepares government viewpoints on proposed legislation concerning media policy.

As of 2002 an independent press council was being organized. This body was conceived by three media organizations: the Syndicate of Slovak Journalists (SSN), the Association of Slovak Journalists (ZSN), and the Association of Slovak Press Publishers. It will receive, consider, and adjudicate complaints of breaches in media code and comprises nine members appointed by core organizations representing journalists and publishers.

Slovak broadcast media is subject to Czechoslovakia's Broadcast Act, the first of its kind in a post-Communist country. The Act was created to give legal existence to an emerging dual system of public and private radio and television in the region. The Broadcasting Act states terms and conditions of allowable broadcasting and standards of advertising and sponsorship, with penalties for noncompliance. The Act also provides for editorial independence and freedom of expression within guidelines of impartiality and objectivity. It also prohibits broadcasting material, which might incite violence or ethnic hatred, instigate war, or promote indecency. Practical issues addressed by the Broadcasting Act include the planning of frequencies and granting of licenses. Under the Broadcast Act, the Slovak Parliament can recall any member of radio and television authorities, if the recall motion is supported by at least 10 percent of Parliament.

The Slovak National Broadcasting Council, established in 1992 to safeguard freedom of speech while introducing a more flexible operating environment, regulates supervision of broadcast laws. Its responsibilities include design of the national information policy, control over broadcasting franchises, development of local broadcasting, and submitting an annual report on the state of broadcasting to the Slovak Parliament. Within the Slovak Broadcasting Council, the Slovak Radio Council and Slovak Television Council approve long-term programming concepts budgets, their own statutes, and the election of general directors for the two public broadcasters.

State-Press Relations

The road to a post-Communist/Slovak free press has been difficult. Although government influence lessened considerably with the fall of Communism in 1989, policies of Prime Minister Vladimír Mećiar earned Slovakia the label, "a totalitarian island in a sea of democracy." Mećiar, in office from 1992 until his defeat in 1998, was reported to have manipulated the press to promote his party, the Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS). This was accomplished by threatening journalists, limiting access, cutting off broadcast stations' electricity, and proposing a prohibitive newspaper tax that would have suffocated small publications.

Prior to the 1998 election, Slovakia's Election Law was amended to prohibit independent media from providing campaign coverage, publishing the results of pre-election polls or for 48-hours before the election, or reporting on any political developments whatsoever. State-controlled broadcast stations were largely exempt from these regulations. In 1997 then-president Michael Kováć—whose political leanings opposed Prime Minister Mećiar—was prevented three times from appearing on camera to urge Slovaks to vote in favor of entry into NATO.

Although government has reduced its attempts to use economic pressure to control the press, defamation laws still exist. In March 2000 a Slovak deputy prime minister accused the editor of an extremist weekly of defamation. The editor—who had criticized governmental permission to use Slovak airspace for Kosovar bombing raids—was found guilty, receiving a four-month suspended sentence and two months probation. In 2001 President Rudolf

During Mećiar's rule, even privatization was used as a tool to manipulate journalists. In 1996 Tatiana Repkova was forced out of her job as editor and publisher of a Slovak national daily when Mećiar's government pressured a friendly company to buy the paper and then dismiss her. Both the purchase of the paper and her firing were legal.

In 1997 the Slovak government proposed increased taxation in an effort to muzzle the press. Its failed attempt to increase the value-added tax on newspapers by nearly 400 percent would have eliminated many independent papers. However, the proposal was withdrawn in the wake of criticism by international media organizations and dissenting government officials.

Under former Slovak Prime Minister Vladimír Mećiar (voted out in 1998), journalists were often barred from the monthly meeting of the ruling party and from Parliament sessions. In addition, reporters rarely gained access to Prime Minister Mećiar at press conferences.

In 2001 Parliament passed Slovakia's first Freedom of Information Act, granting citizens access to virtually all unclassified information from national and local government offices, the president's office, and the Parliament.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Suddenly open to privatization, Slovak media is attracting foreign investment. The market is ripe for innovation and development; it is somewhat undeveloped, the existing press underserves consumers, and emerging free-market businesses need advertising venues. Foreign ownership is permitted, although licensing preference is given to foreign applicants planning to contribute to original domestic programming. The Slovak government offers substantial tax breaks to foreign investors and plans to privatize many state-run institutions, including telecommunications.

Two foreign radio stations have been awarded broadcasting licenses and are on the air. BBC World Service delivers short-wave broadcasts around the clock from Bratislava, Banská Bystrica, and Kośice in English, Slovak, and Czech. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty broadcasts Slovak and Czech programming from Prague 13 hours each day; its editorial offices in Bratislava oversee reporters operating through Slovakia. In addition, a Slovak company and the London-based American firm, Central European Media Enterprises, jointly own the country's first private television station, TV Markiza.

News Agencies

Slovakia is home to the only state-controlled press agency in Europe, the Press Agency of the Slovak Republic (TASR). Until 1992 it was part of the federal Czechoslovak Press Agency (CTK) but has operated independently since then. A private, competing news agency, the Slovak News Agency (SITA) was established in 1997. Since then Slovak journalists have regarded SITA as an unbiased information source.

The two agencies have repeatedly challenged one another legally. In 2000 SITA sued TASR over copyright infringement when the government agency allegedly plagiarized a SITA story. TASR responded by suing SITA for 92 million Slovak koruna (SK) in damages, accusing SITA of stealing customer passwords to access TASR. The state press agency's 72 million SK government subsidy has been challenged by Parliament, suggesting that the agency may redefine its policies to avoid accusations of political influence.

TASR has over 250 employees, including 170 editors and journalists. A modern press agency with foreign correspondents in Washington, Bonn, Moscow, Brussels, Budapest, Warsaw, and Prague, TASR is connected via wire and satellite with other world and national news agencies, generating 400 to 450 reports and 60 photographs daily for some 240 customers. Its documentary department provides research and cutting services, an archive of 250,000 items, and the Daily News Monitor , a brief review of Slovak and Czech media.

A smaller agency, SITA is staffed by 30 trained professionals specializing in financial and business news, though it also covers political, social, and regional Slovak events. SITA also provides its clients with a daily news digest and an information service of traffic and weather.

Founded in 1991, the Slovak Union of Press Publishers (ZVPT) includes over 50 newspaper and magazine publishers. A member of the Paris-based World Association of Newspapers (WAN), ZVPT offers professional training seminars and participates in advising and consulting on media laws. Slovakia's Association of Independent Radio and TV Stations (ANRS) represents its 18 member stations in discussions with government bodies, with authors' rights protection, organizations with telecommunication companies, and other subjects. The Slovak Society for Cable Television (SSKT) unites equipment engineers, manufacturers, suppliers, creators, and operators of the state's rapidly developing cable television sector. Other groups include the Association of Slovak Periodical Publishers, the Association of Independent Radio and Television Stations, and the Union of Slovak Television Creators.

The major association of Slovak journalists is the 2,000-member Slovak Syndicate of Journalists (SSN), which includes 80 percent of Slovak journalists. A member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), its mission is to safeguard free press and journalists' rights and working conditions. The SSN provides unemployment support, maternity leave pay, represents its members in international relations with foreign journalists' organizations, produces the magazine Forum , and organizes press conferences. A pro-government group, the 1,000-member Association of Slovak Journalists (ZSN) broke from the SSN in 1992, but some journalists are members of both groups. Its membership has declined since the defeat of former Prime Minister Mećiar in 1998.

Broadcast Media

Slovakia's broadcast media includes two state-run television stations, three state-run radio stations, 20 private radio stations, and a number of private television stations. Some parts of the country also receive Czech and Hungarian television signals.

Since 1991 Slovak Radio and Television have been public institutions supervised by parliamentary-appointed councils. Prior to 1998, privately owned television could not officially carry political news, and public television served as a mouthpiece for Prime Minister Mećiar and the HZDS party. A 1998 monitoring survey showed that STV devoted 47 percent of its news coverage to the ruling party, 17 percent to coalition parties, and only 13 percent to the opposition, which received overwhelmingly negative coverage. Government and ruling parties receive 62 percent of overall airtime; the opposition only 15 percent.

In the same pre-1998 period, Slovak Radio operated more objectively than STV. Devoting no airtime to editorials, Slovak Radio allotted 55 percent of its time to the government; parliamentary and other central bodies got 36 percent, and the opposition received slightly less than 10 percent.

The nonprofit, public service Slovak Radio has broadcast since 1926. Financed by an annual license fee from each household with a radio receiver as well as by advertising, Slovak Radio also receives government support. Slovak Radio broadcasts 23,000 hours per week on three national networks—each specializing in news, classical music, or rock—reaching 3.5 million across Slovakia. Regional radio (also called Regina) includes ethnic minority broadcasting. In this category, the Hungarian community receives some 40 hours of programming, with 15 hours for Ukrainian and Ruthenian listeners, and half an hour each for Romanic and German minorities.

Established in the wake of independence, the Slovak World Service is geared to expatriate Slovak listeners living abroad wishing to maintain their national identity and proficiency in the Slovak language. Private radio was launched in 1990 and reaches some one-third of the Slovak population each day through 19 stations. Its first and most popular outlet, FUN Radio, broadcasts rock music and reaches 3 million people daily in 70 percent of Slovakia's territory. RadioTwist broadcasts a wider range of music programs and an objective political program competing with public service broadcasting. Radio Koliba's four transmitters reach a fair share of radio audiences in central and eastern Slovakia, while other private broadcasters serve specific regions, reaching no more than 5 percent of the total population. Other stations include RMC Radio, FM Radio DCA, Radio Ragtime, and Radio Tatry.

Television reaches most Slovak citizens; over 98 percent of the population owns at least one television. Some 60 percent watch television daily, while 27 percent watch several programs each week. Slovakia's public broadcaster, Slovak Television (STV), was chartered in tandem with Slovak Radio. STV broadcasts 8,600 hours on 2 channels from its studios in Bratislava, Kośice, and Banská Bystrica, and is financed by license fees, ad sales, and government support. Although public television is popular, private television is providing significant competition.

Launched in 1996, the commercial TV Markiza broadcasts 19.5 hours daily. Its light entertainment format includes the first Slovak soap opera and game shows in addition to news and current affairs. It has enjoyed top place in viewer listings since its first day of broadcasting; 65 percent of Slovak adults watch it daily. Slovakia began installing cable facilities in 1989, and by 2002 dozens of networks were accessible by 27 percent of its population. Slovakia's largest cable operator, SKT Bratislava, serves 70 percent of the capital's population.

Electronic News Media

By 1998 some 10 percent of all Slovak citizens and public schools had Internet access through 10 Slovak Internet

Many newspapers and magazines in Slovakia have embraced new technology, writing and editing their stories on computers; Pravda had introduced a computer system before 1989. All journalism education programs in Slovakia include courses, workshops, and facilities to develop new media.

Education & Training

Over 1,400 students have graduated from the journalism program of Comenius University since its founding in 1952. Its curriculum offers four areas of concentration: theory and history of journalism, press and agency news, radio and television journalism, and advertising. In Trnava, the University of St. Cyril began a dual graduate program of mass media communication and marketing communication in 1997.

The Centre for Independent Journalism in Bratislava is one of four schools established by the Independent Journalism Foundation (IJF) to offer tuition-free training for journalists in Eastern and Central Europe. Funded privately it is operated by veteran journalists from the United States and Europe. The Centre is equipped with state-of-the-art facilities provided by the Freedom Forum, an international free speech organization.

Summary

Since 1989 the media climate in Slovakia has changed from a restrictive, state-run system to a dual system of state and independent media. Between 1990 and 1992, there were more than 15 significant new statutes or modifications of old laws regarding the media. This legislation ensured free speech and set guidelines for the development of private and commercial press enterprises.

With a truly democratic government in place by 1998, Slovakia enjoys a free press climate and a burgeoning media industry. The array of commercial broadcast and print outlets appearing after the fall of Communism have been augmented by the growth of online media, cable, and satellite communication.

Since Slovakia's government and economy stabilized in the late 1990s, the country has attracted and encouraged foreign investment, much of it geared toward media outlets. With these resources and a demanding, educated audience, Slovakia can expect rapid growth in the number, diversity, and types of media available. In the early twenty-first century, Slovakia may narrow the small gap between its media environment and that of western Europe.

Significant Dates

- 1998: Prime Minister Mećiar is ousted by Mikuláś Dzurinda of the Slovak Democratic Coalition (SDK).

- 2000: Slovakia joins The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an international organization of 30 industrialized, market-economy countries.

- 2001: Slovakia's first Freedom of Information Act is passed.

Bibliography

Brecka, Samuel. "A Report on the Slovak Media." Bratislava: National Centre for Media Communication, 2002.

Dragomir, Marius. "Slovakia's Twenty-first Century Journalism School." Central Europe Review (Sept. 21, 2001).

International Journalists Network. "Access to Information Law Adopted in Slovakia." Washington, D.C. (June 1, 2000).

International Press Institute. "Slovakia: 2001 World Press Freedom Review."

——. "Slovakia: 2000 World Press Freedom Review."

Karatnycky, Adrian, Motyl Alexander, and Charles Graybow. "Nations in Transit: Slovakia." Freedom House, 1998.

Lipton, Rhoda. "Final Report: Slovakia." International Center for Journalists, July 1998.

"New Online Publications Offer News on Six CEE Nations" Embassy of the Slovak Republic Newsletter. Bratislava: n.d.

Skolkay, Anrej. "An Analysis of Media Legislation: The Case of Slovakia." International Journal of Media Law and Communications (Winter 1998/1999).

U.S. Department of State. "Country Commercial Guide: Slovakia." Washington, D.C.: 2000.

——. "Slovak Republic Country Report on Human Rights Practices 2000." Washington, D.C.

Vystavil, Martin. "Internet: Supporting Democratic Changes in the Post-Communist Slovak Republic." Reston, VA: The Internet Society, 1995.

Blair Tindall

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: