Turkmenistan

Basic Data

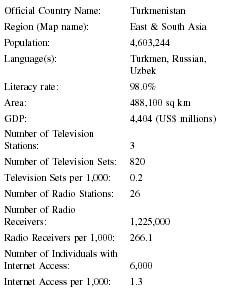

| Official Country Name: | Turkmenistan |

| Region (Map name): | East & South Asia |

| Population: | 4,603,244 |

| Language(s): | Turkmen,Russian,Uzbek |

| Literacy rate: | 98.0% |

| Area: | 488,100 sq km |

| GDP: | 4,404 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Television Stations: | 3 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 820 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 0.2 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 26 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 1,225,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 266.1 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 6,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 1.3 |

Background and General Characteristics

Turkmenistan borders both Iran and Afghanistan on the south and the Caspian Sea on the west, with a total area of 188,456 sq. miles. Mainly a desert country, the Kara Kum, or Black Sand Desert, covers the central part of the republic. The Kopet Dag mountains lie in the south, along the Iranian border. The land has vast reserves of natural gas and oil, and is a leading cotton producer. Of the Central Asian Republics, Turkmenistan remains the most closed and least reformist—essentially a one-man state. It has the longest border with Afghanistan, and its supportive role in supplying humanitarian relief for Afghanistan has been essential, having facilitated more than 30 percent of food aid for Afghanistan.

Turkmenistan was known for most of its history as a loosely defined geographic region of independent tribes. Now it is a landlocked, mostly desert nation of about 4.5 million people (the smallest population of the Central Asian republics and the second-largest land mass). The country remains quite isolated on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, largely occupied by the Qizilqum (Kyzyl Kum) Desert. Many believe traditional tribal relationships still are a fundamental base of society, and telecommunications service from the outside world has only begun to have an impact. Like the Kazaks and the Kyrgyz, the Turkmen peoples were nomadic herders until the second half of the nineteenth century, when the arrival of Russian settlers began to deprive them of the vast expansion needed for livestock.

Today's Turkmen territory was part of the Ancient Persian Empire till the fourth century B.C. when Alexander of Macedonia took over Parthians gained control after the Macedonian Empire crumbled and established their capital at Nisa. Another Persian dynasty of Sassanids gained control in the third century A.D. It was invaded by the Turks in the fifth century A.D. Mongol invasions took place in the tenth century A.D. and Turkmen trace their history from this time when Islam was first introduced. Seljuk Turks seized control in the 11th century A.D. Mongol ruler Genghis Khan seized power in the thirteenth century A.D. Between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries the whole region was Islamized. Mongols continued to rule until the Uzbek invasion.

The Turkmen people exercised opposition to the Czarist forces in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but were defeated eventually and became part of what was called the Transcaspian Region in 1885. The Bolsheviks attempted to dominate the area but met with much opposition, producing years of political disorder. This ceased in 1924 when the Red Army took control of Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, and the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic was established. During the next 60 years, despite religious and political repression, limited advances were made under the Soviet system, especially in the areas of health and social issues. However, Turkmenistan was a relatively neglected republic in the Soviet block. Very few investments were made in industry and the development of the infrastructure was somewhat neglected. The under-representation of the Turkmenistan republic in the Soviet Communist party and the periodic purging of the Turkmenistan Communist party continued throughout this period. In 1985 Saparamurad Niyazov became the Turkmenistan communist party leader, and in 1991 he became President of newly independent Turkmenistan.

Today's ethnic population is 72 percent Turkmen, 9 percent Russian, 9 percent Uzbek, and 2 percent Kazak. 89 percent of the population is Sunni Muslim. 77 percent speak Turkmen as their native language with another 12 percent speaking Russian. In 1990, Turkmen was declared the official language of the country and the transition from Russian to Turkmen was to be completed by January 1, 1996. However, given the ethnic diversity of the country and the lack of updated technical vocabulary in the Turkmen language, Russian is still commonly used by many people, including Turkmen, in urban areas. In May 1992, it was announced that Turkmenistan would change to a Latin-based Turkish-modified script. This is the third type of script adopted by the country. In 1929 Arabic script was altered to Latin. That was in turn altered to Cyrillic script in 1940 as a result of Soviet influence. Sources put literacy at 98 percent of the population without specifying what form that literacy might take.

The post-Soviet government of the Republic of Turkmenistan retains many of the characteristics and the personnel of the communist regime of Soviet Turkmeni-stan. It is a one-party state dominated by its president and his closest advisers, and, as a nation, it made little progress in moving from a Soviet-era authoritarian style of government to a democratic system. As of 2002 the government had received substantial international criticism as an authoritarian regime centering on the dominant power position of President Saparmurad Niyazov. Saparmurad Niyazov, head of the Turkmen Communist Party from 1985, renamed the Democratic Party in 1992, and President of Turkmenistan since its independence in 1991, legally was permitted to remain in office until 2002. Niyazov, however, announced on 18 February, 2001 that he would be stepping down in 2010 because after 70 "age takes its toll." Nevertheless, the 1992 constitution does characterize Turkmenistan as a democracy with separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

In May 1992, Turkmenistan became the first newly independent republic in Central Asia to ratify a constitution. It is also termed a "presidential republic," one that is "based on the principles of the separation of power, into legislative, executive, and judicial branches, which operate independently, checking and balancing one another."

The Law of the Turkmen SR on Language established the Turkmen language as a state language. The Law contains 36 articles dealing with rights of citizens to choose/use language, and guarantees protection of such rights, establishing frameworks for operation of the state language in public authorities, enterprises, institutions, in spheres of education, science and culture, and administration of justice. The law also regulates use of language in names and also in the mass media. There is a special chapter for the protection of the state language. Russian is given the status of "the language of interethnical communication."

Saparmurad Niyazov was unchallenged in the 1992 presidential election. In 1994 the electorate extended his term until 2002, and in 1999 he was declared President for life, thus confirming, in effect, his complete domination of government. There is no political dissent within Turkmenistan, and most political opponents to Niyazov are in exile, or in prison. The Democratic Party has a monopoly on political power, and parliament (the Mejlis) has no real authority. The judicial branch, unreformed since Soviet times, provides no check on executive power. Turkmenistan is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and does not participate in regional military groupings.

The two Turkmen newspapers that were touted as independent, Adalat (Justice) and Galknysh (Revival), are no longer even nominally independent. They were founded by Niyazov's decree in 1997, and they are censored. The president is the founder of all the country's newspapers except Ashgabat . Journalists are state employees, and their assignment is to cover Niyazov. Accordingly, the nation's newspapers and other publications ring with praise for the president and his policies. In addition to employing newspaper staffs the state also controls the distribution of their product. The state-run publishing house has to report directly to the cabinet of ministers since its governing body, the Government Press Committee, was abolished. The top newspapers are the Neytralnyy Turkmenistan , a Russian-language newspaper published six times a week; the Turkmenistan , a Turkmen-language newspaper, published six times a week; the Watan , a Turkmen-language newspaper, published three times a week; the Galkynys , Turkmen-language weekly, mouthpiece of the Democratic Party of Turkmenistan; the Turkmen Dunyasi , a Turkmen-language monthly and mouthpiece of the Ashgabat-based World Turkmens Association; the Adalat (Justice) in Turkmen; and the Edebiyat we Sungat (Literature and the Arts) in Turkmen.

Economic Framework

Turkmenistan is largely a desert with the raising of cattle and sheep, intensive agriculture in irrigated areas, and huge oil and gas reserves. Its economy remains dependent on central planning mechanisms and state control, although the government has taken a number of small steps to make the transition to a market economy. Agriculture, particularly cotton cultivation, accounts for nearly half of total employment. Gas, oil and gas derivatives, and cotton account for almost all of the country's export revenues. In 2002 the government was proceeding with negotiations on construction of a new gas export pipeline across the Caspian Sea, through Azerbaijan and Georgia to Turkey, and was also considering lines through Iran and Afghanistan.

Turkmenistan's economic growth is heavily reliant on exports, benefiting in 2000 from high global commodity prices and the resumption of gas sales to Russia and Ukraine. Agriculture, the largest sector of the economy, is still unreformed and may actually have declined over the past few years. The limiting factor is the scarcity of water resources. Turkmenistan has large deposits of oil and gas, and is able to finance its economic polices through gas sales, most of which are made to Russia and other NIS countries. Convertibility problems top the list of business-related problems for foreign investors. The official exchange rate, required for foreigners, is roughly a fourth of the black-market rate. Foreign firms convert the local currency, the manat, into hard currency with substantial losses. Official corruption is another obstacle to foreign investment, and is fueled by the double exchange rate. In the late 1990s, the GDP ballooned to 17.6 percent (2000), leveled off to real GDP growth at 9 percent in 2001, and is falling to 7 percent in 2002.

During the 75 years of Soviet domination, Turkmenistan was completely dependent on the U.S.S.R. for energy resources, educational materials, banking, postal services, and all major planning and administrative activities. Since declaring its independence, the Republic of Turkmenistan has been working to establish institutional and economic stability. Turkmen nationalism and a reawakening interest in Islam is slowly taking place as traditional beliefs and ways of life are being encouraged and a new national identity is emerging after the dissolution of Communist rule. The introduction of several foreign influences after decades of isolation add to the changing social structure of Turkmenistan.

Although living standards have not declined as sharply in Turkmenistan as in many other former Soviet republics, they have dropped in absolute terms for most citizens since 1991. Availability of food and consumer goods also has declined at the same time that prices have generally risen. The difference between living conditions and standards in the city and the village is immense. Aside from material differences such as the prevalence of paved streets, electricity, plumbing, and natural gas in the cities, there are also many disparities in terms of culture and way of life. Thanks to the rebirth of national culture, however, the village has assumed a more prominent role in society as a valuable repository of Turkmen language and traditional culture.

Most families in Turkmenistan derive the bulk of their income from state employment of some sort. As they were under the Soviet system, wage differences among various types of employment are relatively small. Industry, construction, transportation, and science have offered the highest wages; health, education, and services, the lowest. Since 1990 direct employment in government administration has offered relatively high wages. Agricultural workers, especially those on collective farms, earn very low salaries, and the standard of living in rural areas is far below that in Turkmen cities, contributing to a widening cultural difference between the two segments of the population. In 1990 nearly half the population earned wages below the official poverty line, which was 100 rubles per month at that time. Only 3.4 percent of the population received more than 300 rubles a month in 1990. In the three years after the onset of inflation in 1991, real wages dropped by 47.6 percent, meaning a decline in the standard of living for most citizens. There is almost no competitive business sector in Turkmenistan, and over-regulation continues to stifle any potential for growth in this sector. Due to the lack of transparency and an unwillingness to share information, precise numbers on Turkmenistan's per capita GDP and debt are not available, although the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that the GDP per capita income is $652.

Press Laws

The Law on the Press and other Mass Media, practically the only document regulating the activities of the media in Turkmenistan, was carried on, before the fall of the Soviet Union, by the Supreme Soviet of the Communist party of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic, and signed by the president, Saparamurad Niyazov.

The law prohibits media intrusion into the private lives of citizens or anything that might constitute an attack on their honor and reputation. The republic's laws place a particular accent on the protection of the honor and reputation of the president. In June 1997 a new Criminal Code was passed by the Medzhilis (parliament) in which any infringement into the life of the president could be punishable by 15 years of imprisonment or capital punishment (although in 1999 capital punishment was dropped). For libel or insult of the president the minimum sentence is five years in prison.

Any citizen of Turkmenistan of over 18 years of age has the right to found a media company, as does any association that has been legally registered to operate in the republic. In order to register a periodical publication, it is necessary to submit documentation and if permission is received, the publication can be registered with the advertising-publishing company Metbugat. Then the publication must receive a license to actually publish. All documents submitted for register are forwarded to the personal attention of the vice-premier, the minister of culture. Even though journalists in Turkmenistan tend to censor themselves, the government has an official censor, namely the State Committee for Protection of State Secrets, where even the smallest publications are required to register. Libel is a criminal offense, but in practice it is not an issue because controls on media are more rigid today than in the Soviet era. In order to regulate printing and copying activities, the government ordered in February 1998 that all publishing houses and printing and copying establishments obtain a license and register their equipment.

The government prohibits the media from reporting the views of opposition political leaders and critics, and it never allows even the mildest form of criticism of the president in print. The government has threatened and harassed those responsible for critical foreign press items.

Censorship

The Constitution of Turkmenistan provides for the right to hold personal convictions and to express them freely. In practice, however, the government severely restricts freedom of speech and does not permit freedom of the press. Continued criticism of the government can lead to personal hardship, including loss of opportunities for advancement and employment. Freedom House has consistently rated Turkmenistan as "not free," with the lowest ranking of political rights and civil liberties possible on its scale. A weak judiciary follows the will of the President for Life and is unprepared to protect civil and commercial rights. Civic action is still very risky, though a handful of National Government Offices (NGO), such as water-user associations, has taken up issues at the local level to some effect. Democratic culture in Turkmenistan will require, first and foremost, government receptiveness to reforms and increasing the popular demand for reform among both citizens and governing elites.

Registration remains one of the biggest challenges for the development of nascent civic organizations and only a dozen or so organizations have been registered. Most of these are sport clubs or groups organized under quasi-NGOs, holdovers from the Soviet times. Given the registration constraint, Turkmen NGOs must be more innovative in obtaining legal status. Recently, several organizations were registered as cooperatives, which gives them most of the rights and benefits afforded to noncommercial organizations in the country. NGOs face increasing pressure from the government, which is suspicious of and resists civil society development. Government continues to tighten its grip on the Turkmen society, regularly blocking civil society activities, restricting the media, discouraging educational innovation and trampling citizens' human and religious rights. At present, the Committee for National Security (KNB) actively restricts NGO activity, especially when NGOs' work attracts the attention and presence of international organizations. This negatively influences the attitudes of regional ( velayat ) and district ( etrap ) level officials towards NGOs, making it more difficult than in other countries in Central Asia to increase opportunities for citizen participation in governance.

State-Press Relations

The government completely controls radio and television, and it funds almost all print media. The Government censors newspapers and uses Turkmen language newspapers to attack its critics abroad; the Committee for the Protection of State Secrets must approve prepublication galleys. Russian language newspapers from abroad now are available by subscription and some Russian and other foreign newspapers are also available in several Ashgabat hotels. However, the two nominally independent newspapers established under presidential decree, Adalat and Galkynysh , are no longer even nominally independent.

The constitution guarantees "the right to freedom of thought and to the free expression thereof, and also to obtain information, if it is not a government, service or commercial secret." However, in practice the government severely restricts freedom of speech and does not permit freedom of the press. It completely controls the media, censoring all newspapers and rarely permitting independent criticism of government policy or officials.

There are no independent media outlets. All broadcast outlets that do exist are strictly controlled, and nearly all print media receive their funding from the state.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has recorded attacks on journalism at a level unabated since 1992. Journalists who represent Radio Liberty, which is the only regularly available non-state source of news, seem particularly vulnerable. In order to regulate printing and copying activities, the government ordered in February that all publishing houses and printing and copying establishments obtain a license and register their equipment. Criticism sanctioned by the President of government officials is commonplace. The government has subjected those responsible for critical foreign press items to threats and harassment. The KNB arrested a former presidential spokesman one day after he criticized the government on Radio Liberty. The former press secretary was released 10 days after the arrest, after he said that he was coerced into making antigovernment statements by the radio service. The government revoked the accreditation of the Ashgabat-based Turkmen-language Radio Liberty correspondent in 1996 because of broadcasts by an opposition politician in exile, but it has not prevented him from continuing to file reports. Following his release from a psychiatric hospital in Geok-Depe in April, dissident Durdymurad Khodzha-Mukhammed was warned by a member of the states internal security apparatus to refrain from political activity, including meeting with foreign diplomats. In August after meeting with the British ambassador in Ashgabat, Khodzha-Mukhammed was abducted and beaten severely by unknown persons; he remains in very poor physical condition. Members of Khodzha-Mukhamedós family also reportedly have been threatened with harm if he resumes political activities. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty correspondent Yoshan Annakurbanov was released in November 1997 from a KNB prison but remained under investigation for allegedly attempting to smuggle "military secrets" out of the country. He was forbidden to leave his apartment, meet with journalists and foreign officials, or discuss his case. In August he left the country and now lives in the West.

In this Central Asian nation, the stamp of the first and only post-Soviet leader, Saparmurad Niyazov, is pervasive. Statues and renamed public buildings honor the "Turkmenbashi," or "leader of the Turkmen," add an aftertaste of the Soviet era to contemporary life, a flavor that permeates the news media as well. Niyazov officially gained the title "founder" of the Turkmen media in September 1996. In December 1999, Niyazov was made the country's president for life in an unopposed vote. Despite earlier objections to the idea, Niyazov reversed himself in response to what he termed the people's will. In February 2000, Niyazov decreed that the country's mass media should publish fewer of his pictures. According to the decree, the country's publications must carry pictures of Niyazov only when they were reporting on official meetings. Meanwhile, the president extended his "personality cult" to his parents. The nation's only women's magazine was given the name of his mother. Niyazov's father was named a "Hero of Turkmenistan" in May 2000 and his mother was named a national heroine in July 2000. The Committee on National Security (KNB) has the responsibilities formerly held by the Soviet Committee for State Security (KGB), namely, to ensure that the regime remains in power through tight control of society and discouragement of dissent. The Ministry of Internal Affairs directs the criminal police, which work closely with the KNB on matters of national security. Both operate with relative impunity.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

According to a law passed in December 1992, all permanent residents of Turkmenistan are accorded citizenship unless they renounce that right in writing. Dual citizenship is held by Turkmenistan's 400,000 ethnic Russians. Russian-language newspapers from abroad are available by subscription, and some Russian and other foreign newspapers are all available in several Ashgabat hotels. Since 1999, the government has ceased to restrict citizens' ability to obtain foreign newspapers and a wide variety of Russian and Western newspapers have become available. Prior to that Turkmens who would attempt to obtain their news from other sources abroad were stymied by a ban on subscriptions to foreign newspapers and magazines. The ban, in place since October 1996, applied to individuals and organizations and included Russian publications.

According to a reporter who managed to visit the country, many people who would usually read the state newspapers are unable to because of the country's abrupt switch from the Cyrillic to the Roman alphabet. The tri-language daily Ashgabat dropped its English and Russian sections and is now printed in Turkmen only. The government also ended the publication of Golos Turkmen bashi , the Russian-language daily in the city. Turkmenbashi is the city with the highest concentration of ethnic Russians in the country.

News Agencies

The only news agency existing is the government run Turkmen State News Service (TSNS), the official news agency of the Turkmen government.

Broadcast Media

Cable television already had begun to take root in Turkmen cities by the late 1980s and by the early 1990s the country boasted commercial television stations in at least three cities. The commercial broadcasters, however, disappeared by 1994, ensnared in official allegations of financial impropriety. The state body, National TV and Radio, controls all broadcasting and operates three stations. The State Commission of Radio Frequencies, which is a division of the Ministry of Communications, manages frequencies. Only two radio stations are run from Turkmenistan.

Russian public television, ORT, is available on the airwaves throughout the country, but Russian-language broadcasts into the country provide little deep coverage of Turkmen events. ORT programming is censored by a special commission in Turkmenistan before being aired. Programs that contain nudity or political programs in which Turkmenistan is mentioned negatively are usually subject to censorship.

Apart from ORT, two channels broadcast locally-produced programming, airing mainly official news. Both the content and technical level of television in Turkmenistan has deteriorated since the Soviet era. In August 2000, a new television channel, the "Epoch of Turkmenbashi" was created by the president. The channel features the president for hours daily.

Owners of satellite dishes have access to foreign television programming, and Internet access is available as well; however, satellite dishes and Internet access remain so expensive that they are out of reach for the average citizen. In August 2000, the president urged the Turkmen State News Service (TSNS) to increase its contacts with outside news agencies.

Electronic News Media

The journalists' rights group Reports Sans Frontieres (RSF) included Turkmenistan in its list of 20 Internet enemies.

IT (Information Technology) is regulated by the "Laws on Communication," adopted December 20, 1996. A Presidential Decree of February 24, 2000, promulgated under this law established "Provision 4584" relating to licensing activities and gave strong powers to the Ministry of Communication. As a result a number of licenses were repealed. The state provider STC "Turkmen Telecom" has become essentially the only method of access.

It is presidential policy reflected in the "Social and Economic Reforms in Turkmenistan in the Period to 2010" decree to develop advanced IT in Turkmenistan. According to IT Forecaster research, Turkmenistan belongs to the category of "strollers," countries who face more difficulties in catching up since their populations and infrastructures constrain IT expression.

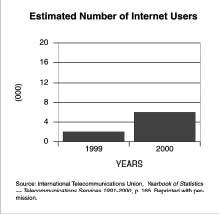

Due to a lack of infrastructure, most Internet access center activity provides access to NGO. An Internet Access and Training Project Centre is administered by IREX and is a part of the American Centre. The Centre provides Internet training, and use of a computer room for alumni of U.S. funded educational programs. In May of 2000 the number of Internet registered users was 1,200, 40 percent of whom were private users. Over 95 percent of Internet and e-mail users are in Ashgabat.

Education & Training

The government does not tolerate criticism of its policy or the president in academic circles, and it discourages research into areas it considers politically sensitive. The government-controlled Union of Writers has in the past expelled members who have criticized government policy; libraries have removed their works.

Similar to programs in other Central Asian countries, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has sponsored training programs in journalism to high school and university level students. Major universities such as the Magtymguty State University in Ashghabat maintain programs in journalism that had originally been designed under the Soviet system, and two institutions have initiated the new program of international journalism. No media programs are currently funded in Turkmenistan because of pervasive government control and lack of commitment to economic and political reforms.

Summary

Journalists are state employees and their assignment is to cover the president's daily activities, which are detailed on television. The constitution guarantees "the right to freedom of thought and to free expression." However, in practice, the government severely restricts freedom of speech. It completely controls the media, censoring all newspapers and rarely permitting independent criticism of government policy or officials. The country has "one of the worst records for press freedom in the former Eastern bloc and one of the worst media climates in the world," according to the Canada-based International Freedom of Expression Exchange forum. The Committee to Protect Journalists has recorded attacks at a level unabated since 1992. Journalists who represent the US-funded Radio Liberty, which is the only regularly available non-state source of news, seem particularly vulnerable to harassment.

The trend to more oppressive governance and less individual freedom only has intensified over time in Turkmenistan. Since 2000, control of the media has been further impeded by the drastic reduction of Russian produced TV programs, as President Niyazov reduced to a few hours in the evening, relayed from the Russian television channel ORT, which has the biggest audience in the country. ORT programs are censored by a special commission in Turkmenistan before being aired, and those containing nudity or reporting negatively on Turkmenistan are usually subject to censorship. The second blow to individual choice in media was the revocation of Internet provider licenses in 2000.

Bibliography

BBC News. "Country Profiles: Turkmenistan." Available from news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/world/asia/pacific/country_profiles.stm .

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). World Factbook: Turkmenistan. Available from http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/html .

Committee for the Protection of Journalists. "Attacks on the Press in 1997." Available from www.cpj.org/pubs/attacks97/europe/turimenistan.html .

European Institute for Media. "Media in the CIS." Internews-Russia. Available from www.internews.ru/books/media1999/67.html .

Freedom House. European Institute for Media "Turkmenistan," Eds. Adrian Karatnycky, Alexander Motyl and Charles Graybow. Available from www.freedom house.org/nit98 .

ICFJ-International Journalists' Network. "Turkmenistan." Available from IJNet.org .

IFEX Communique. "Turkmenistan: Freedom of Expression Still Lagging." 2 February 1999. Available from www.communique.ifex.org

IFEX Communique. "Turkmenistan: State Control of Media Pervasive." Available from www.communique ifex.org .

IJNet. "Father of All Turkmens' renames the women's magazine" August 3, 2000. Available from www.ijnet.org/Archive/2000/8/4-7313.html .

IJNet. "Turkmen leader's image to appear less in print" February 2000. Available from www.ijnet.org/Archive/2000/2/3-6592.html .

IJNet. "Turkmen president stars on his own television channel," August 9, 2000. Available from www.ijnet.org/Archive/2000/8/11-7318.html .

IJNet. "Turkmen president urges foreign news contact, but maintains censorship of TV" August 3, 2000; Available from www.ijnet.org/Archive/2000/8/4-7311.html .

IPI. "World Press Freedom Review, Turkmenistan," IPI Report, 1999.

IPI Report. "World Press Freedom Review," International Press Institute. (December 1993); p. 64. Reporters Sans Frontieres, "1997 Report." Available from www.calvacom.fr/rsf/RSVA/RappVA/EuropVA/TURKA.html .

RFE/RL "Turkmenistan: Niyazov Named President for Life," Bruce Pannie, December 20, 1999.

Turkmenistan Constitution. Section II, Article 26. Available from www.dc.infi.net/üembassy/constionA.html#constionA1 .

UNDP. "Today's technological transformations-Creating the network age." Available from www.undp.org/hdr2001/chaptertwo.pdf .

UNDP. "Turkmenistan: Education Sector Review." 1997

U.S. Department of State. "1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices." Available from www.state.gov .

Viginia Davis Nordin

If not, can you suggest a source that can?

Sincerely