Turkey

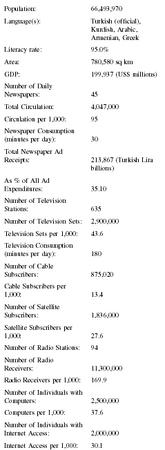

Basic Data

| Official Country Name: | Republic of Turkey |

| Region (Map name): | Middle East |

| Population: | 66,493,970 |

| Language(s): | Turkish (official),Kurdish,Arabic,Armenian,Greek |

| Literacy rate: | 95.0% |

| Area: | 780,580 sq km |

| GDP: | 199,937 (US$ millions) |

| Number of Daily Newspapers: | 45 |

| Total Circulation: | 4,047,000 |

| Circulation per 1,000: | 95 |

| Newspaper Consumption (minutes per day): | 30 |

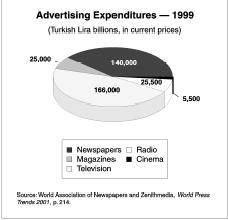

| Total Newspaper Ad Receipts: | 213,867 (Turkish Lira billions) |

| As % of All Ad Expenditures: | 35.10 |

| Number of Television Stations: | 635 |

| Number of Television Sets: | 2,900,000 |

| Television Sets per 1,000: | 43.6 |

| Television Consumption (minutes per day): | 180 |

| Number of Cable Subscribers: | 875,020 |

| Cable Subscribers per 1,000: | 13.4 |

| Number of Satellite Subscribers: | 1,836,000 |

| Satellite Subscribers per 1,000: | 27.6 |

| Number of Radio Stations: | 94 |

| Number of Radio Receivers: | 11,300,000 |

| Radio Receivers per 1,000: | 169.9 |

| Number of Individuals with Computers: | 2,500,000 |

| Computers per 1,000: | 37.6 |

| Number of Individuals with Internet Access: | 2,000,000 |

| Internet Access per 1,000: | 30.1 |

Background & General Characteristics

In 1923 Mustafa Kemal (188l-1938) founded the modern Republic of Turkey ( Türkiye Cumhuriyeti ). Later in his life (1934), for his dedicated service to the state and people of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal was honored with the designation Atatürk (Father Turk) by the Grand National Assembly. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, allowed Atatürk to pursue his objectives of freeing and keeping Anatolia whole. Having become an accomplished military officer under the Ottomans, including having earned his military fame at Gallipoli where the Allied forces were halted in their progress, Atatürk maintained enough military savvy to manage the eradication of the remaining Greek occupying forces from the area (1921-1922) in the aftermath of Ottoman dissolution. With his military prowess and political charisma Atatürk outlasted the Sultanate which ended on November 1, 1922—and had advocated the partitioning of Turkey with the Allied forces—and established the Republic of Turkey almost exactly one year later, October 29, 1923.

Understanding Atatürk's leadership is essential for deciphering reasons behind the state of the press and the media that exists in Turkey today. Atatürk's initial leadership and legal enactments set Turkey on the path it is currently journeying. He provided Turkey with the positive building blocks for creating a strong nation-state, but also negatively allowed for the beginning of some of the repressive practices concerning freedom of the press that are still being suffered.

By 1928, Atatürk had implemented the reforms necessary for Turkey to become a secular state; he removed the constitutional provision decreeing Islam as the state religion, abolished the caliphate which was symbolic of the Sultanate's religious authority, eliminated all other Islamic institutions, introduced a Westernized system of law and dress, and also instituted the use of the Latin calendar and alphabet. As well, by 1934, women obtained the right to vote. All of these reforms, besides fostering the secularization of the state of Turkey, also emphasized Atatürk's desire to move Turkey toward its European influences. As a result of Atatürk's massive, sweeping reforms his administration gained the status of an ideology by 1931—Kemalism or Atatürkism. The guiding principles of this ideology, while describing the foundational as well as the sometimes seemingly chaotic and contradictory nature of Atatürk's tenure, have been labeled as: republicanism, nationalism, populism, statism, secularism, and revolutionism.

As was mentioned, though Atatürk's regime was monumentally important for the founding of Turkey, it also facilitated some long-term, detrimental principles.By 1926, through the combined cooperation of landowners, the country's bourgeoisie, and the civil and military bureaucracies, Atatürk ruled as an autocrat. All opposition had been silenced. Yet, despite the relatively draconian nature of his rule, Atatürk's policies brought stability to the newly founded country; setting Turkey on a course to United Nations membership in 1945 and NATO membership in 1952 (NATO membership is mentioned as an expression of Atatürk's Europeanizing principles; it actually contradicts with his stance on neutrality). Kemal Atatürk ruled for a total of 14 years, being reelected in 1927, 1931, and 1935, and died in 1938.

From Turkey's founding until 1946, it was largely a single party operation. In 1946 a multiparty political system was established. Primarily (despite the years 1960, 1961, and 1980-1983 when the military took direct, intervening action to halt coups meant to override the state's policies of secularism) Turkey has been civilian ruled—at least theoretically. To be accurate, Turkey's civilian rule is a rather broadly defined notion of the idea. The military in Turkey has always had significant veto power concerning any action of which it did not approve. In many senses, civilian rule in Turkey could be thought of as a legitimizing front for military rule.

That being as it is, Turkey is, in the early twenty-first century, a parliamentary democracy as guided by its November 1982 constitution enacted by popular referendum. Under this constitution there is universal suffrage for all citizens over the age of 18. Legislative power rests in the National Assembly (550-member unicameral body directly elected to five-year terms), the head of government is the prime minister (representing the majority party or coalition in parliament and appointed by the president), and the president (chief of state) is chosen by parliament for seven-year terms.

Country Geography

Turkey is located on the northeastern edge of the Mediterranean Sea and is often thought of as the bridge country between Europe and the Middle East. In fact it fluctuates between being designated as being part of southeastern Europe or as part of northwestern Asia. Literally, the portion of Turkey that lies west of the Bosporus Strait, the strait of the Dardanelles, and the Sea of Marmara (which altogether are known as the Turkish Straits and are extremely strategic as they are the only outlet linking the Black Sea with the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas) is designated as part of Europe. The rest of the country is considered Middle Eastern and/or Asian. This amounts to roughly 3 percent of the land and 8 percent of the population being in Europe. The rest of the land (97 percent) and people (92 percent) are in the Middle East.

To the northwest of Turkey lies Greece and Bulgaria. To the west lies the Aegean Sea. Directly north is the Black Sea. On Turkey's northeast to its southeast, in descending order, lies Georgia, Armenia, the Azerbaijani exclave of Naxçivan, and the northwestern tip of Iran. South of the country, east to west, lie Iraq and Syria. Also south of the country, but separated by the water of the Mediterranean, lie the islands of Crete and Rhodes belonging to Greece, and the island of Cyprus which, as of 1974, is jointly shared and disputed between Turkey and Greece—Turkey occupies the northern portion with a UN buffer zone lying between the northern and southern sections. In 1983 Turkish controlled Cyprus designated itself the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, but Turkey is the only country recognizing this designation. In contrast, the southern section, controlled by the Greek Cypriot government, is internationally recognized.

Turkey's total land area, depending on the source, is between 780,580 square kilometers and 779,452 square kilometers (301,380 square miles and 300,948 square miles)—somewhat larger than Texas. Mt. Ararat, the legendary location of Noah's Ark, is in the eastern section of the country. All told, Turkey is divided into 80 iller (provinces) with Ankara being the capital city and Istanbul being the largest.

State of the Press

The press can be considered semi-vigorous, semi-independent, and often on the defensive. There are numerous dailies, weeklies, and other publications available, but the government has established numerous laws that stifle freedom of expression.

Positively, the press often opposes these laws, being seen as the voice of the conscience of the nation and trying to be a check on the government. This causes numerous government imposed shutdowns of press institutions and also causes many journalists to face state sponsored intimidation, fines, and prison time. Negatively and conversely, the press also often inverts and becomes the mouthpiece of governing political parties and of large corporations in order to receive social, political, and monetary benefits.

The use of the press and broadcasting stations as the organ of large corporations is currently a major concern in Turkey. Media centralization/concentration in the hands of ever fewer owners threatens the health of quality journalistic output and quality journalistic practice in the country and is also becoming detrimental to journalists' ability to maintain employment. In February of 2001 some 4,000 people in the media lost their positions. The International Federation of Journalists blamed the Turkish government for allowing such a state of media concentration where this could happen.

The trend continues to worsen with Aydin Doǵanan and his company Doǵan Group, one conglomerate, owning 70 percent of all Turkish media. Doǵan Group owns numerous papers, including Hurriyet and Milliyet , several leading magazines, printing houses, a distribution network, and the Doǵan News Agency. They own and control the radio stations Radyo D, Radyo Klüp, Foreks, and Hur FM, along with the television stations Kanal D, CNN-Turk, Bravo TV, and Kanal D Europe. All told, as of 2001, Doǵan Holding possessed more than 31 media oriented organizations, including some of the most influential broadcasting and press companies in the country.

While there are cross-sector broadcasting restrictions on media companies and ownership percentage limitations meant to create a greater sense of equability and diversity in the media arena (though even these have been increased; such as individual limitations being raised from a maximum 20 percent stake in a television station to a 50 percent stake), as in many other portions of the world, the larger the conglomerate the easier regulations are side-stepped. Thus, instead of the regulations providing a more equitable playing field they create insurmountable hurdles for everyone except the conglomerate, providing a monopolistic market for the large corporation. Typically, less competition means reporting accuracy falls, simply less is reported, and the greater the likelihood for corruption. For instance, it is likely that with a large concentration of media ownership occurring and the ban on larger media groups bidding for state tenders being lifted fraud will go unreported due to the bidders having inordinate access to those in power because they are themselves in power as well. An example of the potential of this type of scenario was enacted in April 2001 when Dinç Bilgin, the owner of the Sabah group, was arrested and accused of embezzling funds after the Turkish government seized Etibank, a small private bank he owned.

Underscoring all of the above is a statement offered by journalist Enis Berberoglu, "I sometimes wonder who is really my boss. Aydin Doǵan or the politicians in Ankara?" Berberoglu's statement, as much of the above, implicitly suggests the power orientation that is involved as large corporations buy up media more for economic or social benefits rather than because of a passion for journalism. A final statement from one of the Turkish new media corporate owners, Korkmaz Yigit—quoted in I Am Ashamed but I Am a Journalist —makes the power orientation more explicit. Yigit explains, "When you grow economically, there will be people attacking at you. But, if you have the media power in your hand, they will think twice before attacking you. This [entering into media] has a defensive aim. They cannot attack you." And therein lies the concern.

Dailies

Turkey's dailies are published primarily as morning editions, but there are some evening papers filling out the offerings. Dailies are published seven days a week, with some papers printing multiple daily editions. As well, larger circulation dailies include color extras in their Sunday editions, analogous in principle with press traditions in the United States and United Kingdom.

The daily foreign language press remains relatively small, but weekly, journal, and quarterly publications bolster this. The English language Turkish Daily News coming out of Ankara holds the largest foreign language circulation at 54,000 and is also available on the Internet. Istanbul houses the Greek language daily Apoyevmatini (circulation 1,200) and the Armenian language Nor Marmara (circulation 2,200). Additionally, other English, French, and German foreign dailies are available in the larger cities.

The largest dailies originate from Istanbul and almost all papers from the city are published simultaneously in Ankara and Izmir, and some in Adana. These papers are distributed nationally to even the small towns and are significant competition to papers produced in other various large and small cities throughout Turkey that are circulated only provincially or locally. From at least an electronic perspective though, local newspapers are not being left behind. On the Internet site of the Office of the Prime Minister—Director General of Press and Information ( Basin Yayin ve Enfomayson Genel Mürdürlüğü ; www.byegm.gov.tr ) there are links to 58 local papers above and beyond national dailies.

The largest dailies by circulation include: Hürriyet (circulation 542,797), Milliyet (circulation 630,000), Sabah (circulation 550,000), Türkiye (circulation 450,000), and Zaman (circulation 210,000). Furthermore, due to the significant expatriate population of Turkish workers in Germany, Istanbul's top circulating papers are also published in Munich. Also, as might be imagined, four of the top circulating dailies are also considered as the "most popular' in Turkey: Sabah , HürriyetMilliyet , and Zaman .

Milliyet and Cumhuriyet (circulation 75,000) are considered to be dailies that are among the most serious and influential in the country. Milliyet is a moderate-liberal independent and the moderate-liberal pro-RPP Cumhuriyet , one of Turkey's oldest papers being founded in 1924 to support Atatürk's revolution, has been referred to as the New York Times of the Turkish Press. Other papers that could be considered for this category could include: Hürriyet , due to its independent nature and large circulation, even though it can be sensationalist and the right-wing, conservative, pro-JP Tercüman (circulation 32,869). Outside of Istanbul and surrounding areas, Yeni Asar (circulation 60,000)—originating in Izmir from the Aegean region and political in focus—is considered to be the best-selling quality daily.

The oldest running dailies still in publication are Yeni Asir ( New Century ) out of Izmir, founded in 1895 and Yeni Adana out of Adana, founded in 1918. Prices for dailies averages around US$.25.

A listing of principle dailies includes:

In Adana

- Yeni Adana. Circulation 2,000; founded 1918; political; Proprietor and editor-in-chief, Çetin Remzi Yüüreóir

In Ankara

- Ankara Ticaret . Circulation 1,351; founded 1954; commercial; Managing editor, Nuray Tüzman; Editor-in-chief, Mummer Solmaz

- Belde . Circulation 3,399; founded 1968; Proprietor, Ilhan Işbilen

- Tasvir. Circulation 3,055; founded 1960; Editor, Ender Yokdar

- Turkish Daily News . Circulation 54,500; founded 1961; English; Publisher, Ilhan Çevik; Editor-in-chief, Ilnur Çevik; Internet, www.turkishdailynews.com

- Türkiye Ticaret Sicili . Founded 1957; commercial; Editor, Yalcin Kaya Aydos

- Vakit . Circulation, 3,384; founded 1978; Managing editor, Nali Alan

- Yeni Tanin . Circulation 3,123; founded 1964; political; Managing editor, Ahmet Tekeş

- Yirmidört Saat . Founded 1978; Proprietor, Beyhan Cenkçi

In Eskisehir

- Istikbal . Founded 1950; Editor, Vedat Alp

In Gaziantep

- Olay Manager Erol Maras

In Istanbul

- Apoyevmatini . Circulation 1,200; founded 1925; Greek; Editor, Istefan Papadopoulos

- Bugün . Circulation 184,884; founded 1989; Proprietor, Önay Bilgin

- Cumhuriyet . Circulation 75,000; founded 1924; liberal; Managing editor, Hikmet Çetinkaya; Internet, www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/a/w

- Dünyald . Circulation 50,000; founded 1952; economic; Editor-in-chief, Nezih Demirkent; Internet, www.dunya.com )

- Fotomaç . Circulation 250,000; founded 1991; Chief officer, Ibrahim Seten; Internet, www.fotomac. com.tr

- Günaydin-Tan . Founded 1968; Editor-in-chief, Seckin Turesay

- Hürriyet . Circulation 542,797; founded 1948; independent political; Proprietor, Aydin Doǵan; Chief editor, Ertuǵrul Özkök; Internet, www.hurriyet. com.tr

- Maydan . Founded 1990; Proprietor, Refik Aras; Editor, Ufuk Guldemir

- Milli Gazete . Circulation 51,000; founded 1973; pro-Islamic, conservative; Editor-in-chief, Ekrem Kiziltaş; Internet, www.milligazete.com.tr

- Milliyet . Circulation 630,000; founded 1950; political; Publisher, Aydin Doǵan; Editor-in-chief, Derya Sazak; Internet, www.milliyet.com.tr

- Nor Mamara . Circulation 2,200; founded 1940; Armenian; Proprietor and Editor-in-chief, Rober Haddeler; General manager, Ari Haddeler

- Sabah. Circulation 550,000; Proprietor, Dinç Bilgin; Editor, Zafer Mutlu; Internet, www.turkiye gazetesi.com

- Yeni Nesil . Founded 1970 as Yeni Asya ; political; Editor-in-chief, Umit Simsek

- Yeniyüzyil . Editor, Kerem Çaliskan

- Zaman. Circulation 210, 000; founded 1962; political, independent; Managing editor, Adem Kalac; Internet, www.zaman.com.tr

In Izmir

- Rapor Circulation 9,000; founded 1949; Owner Dinç Bilgin; Managing editor, Tanju Ateşer

- Ticaret Gazetesi . Circulation 5,009; founded 1942; commercial news; Editor-in-chief, Ahmet Sukûti Tükel; Internet, www.ticaretgazetesi.com

- Yeni Asir . Circulation 60,000; founded 1895; political; Managing editor, Aydin Bilgin; Internet, www.yeniasir.com.tr

In Konya

- Yeni Konya . Circulation 1,657; founded 1945; poitical; Chief editor, Adil Gücüyener

- Yeni Merem . Circulation 44,000; founded 1949; political; Proprietor, M. Yalçin Bahçivan; Chief editor, Tufan Bahçivan; Internet, www.yenimerem.com

Weeklies and other Periodicals

Among the weeklies, Istanbul's Girgir is the undisputed leader. The paper is well known for its political satire and boasts a circulation of 500,000; outselling any other weekly in publication by hundreds of thousands. Of course, weeklies tend to be more niche oriented in general, Girgir simply exploits a niche that is extremely broad in its appeal and they make it intellectually accessible and aesthetically palatable— socio-political commentary laced with humor. This said to both note Girgir's singular impact upon Turkish society, but as well to note that circulation statistics are not the sole criterion for judging importance to society; many of the other weeklies provide needed and important socio-intellectual stimulation as well, fulfilling a valuable civic function, despite their circulation numbers (this of course could be echoed for dailies, periodicals, or any other press publication).

Turkey's oldest running periodical currently in publication, as well as what appears to simply be the oldest publication still running overall, is Istanbul Ticaret Odasi Mecmuasi founded 1884. It is the English quarterly journal of the Istanbul Chamber of Commerce (ICOC).

A listing of major weeklies includes:

In Ankara

- EBA Briefing . Founded 1975; published by Ekonomik Basin Ajansi (Economic Press Agency); political and economic survey; Publishers, Yavuz Tolun, Melek Tolun

- Ekonomi ve Politika . Founded 1966; economic and political; Publisher, Ziya Tansu

- Türkiye Iktisat Gazetesi. Circulation 11,500; founded 1953; commercial; Chief Editor, Mehmet Saǵlam

- Turkish Economic Gazette . Published by UCCET

- Turkish Probe . Circulation 2,500; English; Publisher A. Ilhan Çevik; Editor-in-chief, Ilnur Çevik

In Antalya

- Pulse . Politics and business; Editor-in-chief, Vedat Uras; Internet only, www.ada.net.tr/pulse

In Istanbul

- Aktüel . Managing editor, Alev Er

- Bayrak . Circulation 10,000; founded 1970; political; Editor, Mehmet Güngör

- DoǵananKardes . Circulation 40,000; founded 1945; illustrated children's magazine; Editor, Şevket Rado

- Ekonomik Panorama . Founded 1988; General manager, Aydin Demirer

- Ekonomist . Founded 1991; General Manager, Adil Özkol

- Girgir . Circ. 500,00; satirical; Proprietor and editor, Oǵuz Aral

- Istanbul Ticaret . Founded 1958; commercial news; Publisher, Mehmet Yildirim

- Nokta . Circulation 60,000; Editor, Arda Uskan

- Tempo . Founded 1987; Director, Sedat Simavi; General manager, Mehmet Y. Yilmaz

- Türk Dünyasi Araştirmalar Dergisi Director, Sedat Simavi; General manager, Mehmet Y. Yilmaz

Economic Framework

Turkey can be considered to have both the vital and dynamic economy of a developing/industrializing nation as well as its instability. The country's major industries include: textiles, food processing, autos, mining (coal, chromite, copper and iron ore, mercury, antimony, boron), steel, petroleum, construction, wine, chemical fertilizer, lumber, and paper. Notwithstanding new forms of commercialization, traditional agriculture, using 4 percent of the land for crops and 16 percent as pastureland, still accounts for 40 percent of employment in the country. The main crops are: tobacco, cotton, wheat, barley, corn, rye, oats, rice, figs, olives, raisins, sugar beets, pulse, and citrus. Primary livestock are cattle, sheep, and goats. Overall, as of 2000, approximately 25 percent of GDP comes from industry, 16 percent from agriculture, and 59 percent from government and private services.

Foreign investment in Turkey remains low, due to any number of factors including double digit inflation (39 percent as of 2000) that has plagued the country for years, human rights abuses, drug trafficking, censorship issues, and the military's continual intervention in politics. Stricter control of economic matters by Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit's government and IMF-backed support may enhance Turkey's future economic prospects concerning outside capital inflow as well as better internal creation of capital. However, as of 2001, a number of experts remained skeptical concerning Turkey's economic potential. Additionally in March 2001, in a populist uprising thousands protested the IMF-backed austerity plan.

As of 2000 it was estimated that GDP per capita stood at US$6,800 (677,621 liras to the dollar).

Press Laws

Largely, Turkey has not been known for the positive nature of the government's orientation toward the press. Laws have typically been repressive in nature concerning freedom of expression. However, there has been a recent, encouraging semi-shift in trends due to Turkey's desire to gain membership into the European Union (EU). The EU has been consistent in requiring improvements in Turkey's human rights record as well as their economic infrastructure. All of this accords to some loosening in the restrictive laws of the past. Yet, it is by no means a straight road of improvement. Sometimes intermingled with the improvements are offsetting legal enactments that hinder press/broadcast freedoms through new approaches even as the old methods are being abolished.

Actions of the 1994 government created Turkish Radio and Television Supreme Council ( Radyo Ve Televizyon Üst Kurulu, RTÜK) are a case in point relating current damaging practices of the Turkish government. RTÜK was created to keep firmer regulatory control over television and radio. In 2000, it ordered more than 4,500 days of suspension on media organizations for violations of the country's broadcast principles. Yet apparently, it was perceived that RTÜK was being hindered in performing its restricting practices, because an early June 2001 legal decision bestowed further constricting, regulatory powers on the RTÜK. This decision was to allow the agency to impose fines ranging from $8,500 to $85,000 if any station seems to threaten "the indivisible unity of the state with its people or Ataturk's principles and revolutions … (or) the national and moral values of society and the Turkish family structure." Punishment, in this scenario, could also have been levied for broadcasts which cause the population to experience feelings of "hopelessness and pessimism." This measure was subsequently vetoed by President Ahmed Necdet Sezer on June 18, 2001.

A more positive note concerns a 1999 speech given by the chief justice of the constitutional court, Ahmet Necdet Sezer, who as of May 2000 became the first modern Turkish president without military command experience or an active political background. Sezer, in the 1999 speech, criticized Turkey's 1982 constitution as restricting democratic rights and freedoms. Criticism is one thing and positive legal enactments are another, but as previously noted, due to Turkey's desire to gain admittance into the EU there is likelihood for improvement in oppressive laws and practices if for economic rather than humanitarian reasons.

Also, while dealing with the heavy-handed RTÜK remains a reality, recent legal decisions enacted in August 2002 seem to be the most promising yet.

Censorship & State-Press Relations

Censorship in Turkey remains ubiquitous. Especially sensitive issues include the military, political Islam, and the Kurds. Generally, any printed or broadcast issues that are deemed detrimental to national security, disruptive of the peace, contrary to governmental views on secularism, or critical of those in power have the possibility of being censored along with the offending journalist and press/ broadcast organization receiving punishments; which, according to human rights organizations reports, have included arrest, criminal prosecution, imprisonment, and even attacks by the police.

One of the largest censorship issues on the "international radar screen" for Turkey remains its treatment of the Kurdish population. The government of Turkey has promoted a campaign of intolerance toward the Kurdish population that has been labeled by human-rights organizations as genocidal at times. As a lesser portion of such actions, even though 20 percent of the population is Kurdish (80 percent being Turkish), teaching in the Kurdish language, all Kurdish-language publications and Kurdish-language broadcasts was strictly forbidden for years. In 1991, the Law Prohibiting Languages Other than Turkish was repealed allowing the public use of oral and written Kurdish, but this did not apply to broadcasting. Due to the Law Concerning the Founding and Broadcasts of Television and Radio (No. 3984, adopted April 13, 1994, especially Article 4[t]), broadcasting in Kurdish remains forbidden. Also, an October 2001 parliamentary vote for 34 revisions in the constitution included the abolishment of capital punishment in all areas except for times of war, acts of terrorism—of which all those currently on death row are convicted, and acts of treason. With the October 2001 ruling Kurdish broadcasting was supposed to be allowed, but such broadcasting had always been seen as an action of treason against the state in the past, and with treason still a provision allowing for the death penalty it was unlikely that anyone would be attempting such broadcasts. Thus, this law was expected to "look good on the books," but be negligible in reality.

However, a recent parliamentary vote in August 2002 has guaranteed the legalization of Kurdish broadcasting and education and the abolishment of the capital punishment except solely in times of war. This vote has been seen as another step being taken by the Turkish government to bolster their possibilities of being accepted for EU membership, but nonetheless it is welcomed news. Despite this promising piece of legislation, the government's historically repressive actions have underscored the importance of having the option to utilize foreign satellite broadcasting channels on behalf of the Kurdish population in Turkey as one small means to attempt to rectify ongoing injustices. While there seems to be hope available, yet, at the end of 2001, 13 journalists were still imprisoned primarily due to affiliation with pro-Kurdish or leftist publications.

Other recent examples of censorship and or other limitations of press/broadcast freedom include: RTÜK banning broadcasting by Ozgür Radio for a period of 180 days in December 2000 for allegedly having slandered Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash on air; 20 attacks on, 30 arrests of, and 18 jailings of journalists while in the line of duty in 2001; the continuing imprisonment of academic Fikret Baskaya since June 2001, sentenced under Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law , for writing an article on the Kurdish issue; the January 2002 charging of the Turkish publisher Abdullah Keskin for violating Article 8 of the Anti-Terror Law by publishing a translation of a U.S. journalist's book about the Kurdish minority in Turkey and Keskin's subsequent charging and sentencing in April 2002 to a six-month prison sentence that was converted into a $500 fine.

Among the plentitude of Turkish laws that have the potential of being used to censor media a couple others include Article 33 of the Radio and Television Law which allows the simple revocation of a broadcasting license or a warning being give with subsequent closure of a broadcasting outlet for up to a year and Article 35 of the same law that also permits the confiscation of equipment if a station continues to broadcast following the imposition of a ban. These sanctions are among the most commonly applied. One final example of restrictive regulation is Article 25 of Law 3984 which states that "when national security is clearly threatened or when there is a risk of a serious breach of the peace, the prime minister may intervene to prevent a program being broadcast."

Despite a relatively bleak picture that has been presented concerning censorship (introducing only the very beginning of the issue) there are also organizations that do encourage and provide social sustenance for Turkish journalists. Aiding and representing these journalists in their struggle against censorship and other abuses in Turkey are various associations including: Basin Konseyi (Press Council), the Turkish Journalists' Association, the Journalists' Federation, the Progressive Journalists' Association, and the Contemporary Journalists' Association.

The Turkish Journalists' Association (Turkiye Gazeteciler Cemiyeti or Turkiye Gazeteciler Sendikasi (TGS); founded June 10, 1946; more than 2,900 members all from all over Turkey with the majority based in Istanbul; Chair. Nail Gureli; Internet, www.tgs.org.tr ) is Turkey's oldest and largest professional organization. Its Istanbul branch is Çaǵdaş Gazetciler Derneǵi (Progressive Journalists' Association; Internet, www.cgd.org.tr ). An example of the work that TGS has recently been doing is the newly drafted Declaration of Rights and Responsibilities accepted by TGS on November, 18, 1998. It is an important document stating the ethical responsibilities of journalists towards society as well as strongly supporting their freedom of expression. It has been signed by over 3,500 journalists and has been accepted as the primary national code of ethical journalistic conduct.

Another earlier document that has been important in reaffirming the charge of journalism is the Code of Professional Principles of the Press adopted by the Basin Konseyi (Press Council) in April 1989.

However, despite positive moves made on the part of the Turkish government, it must be recognized that Turkey currently imprisons more journalists than any other country in Europe or the Middle East.

Attitude toward Foreign Media

Turkish attitude toward foreign media remains ambivalent. The government is happy to have correspondents and bureaus present in their country disseminating information to the broader world, so long as it is primarily positive. Though somewhat rare, if the government feels that reporting boundaries have been breached correspondents can be (and have been) dismissed from the country. Overall, Turkey has remained focused on analyzing and critiquing the publication and slant of particular articles/issues by foreign media and has remained more akin to Atatürk's traditional stance of neutrality as concerns boycotting whole countries.

News Agencies

Eight major national news agencies in Turkey with five of the eight being based in Ankara and the other three in Istanbul include (in alphabetical order):

- Anatolian News Agency (founded in 1920; Ankara; Chair. Ali Aydin Dundar; Gen. Dir. Behiç Ekşi)

- ANKA Ajansi (Ankara; Director general Müşerref Hekimoglu; www.ankaajansi.com.tr )

- Bagimsiz Basin Ajansi [BBA] (Istanbul)

- EBA Ekonomik Basin Ajansi (Economic Press Agency; founded 1969; Ankara; private economic news service; Propr. Melek Tolun; Editor, Yavuz Tolun; Internet, www.ebanews.com )

- Hürriyet Haber Ajansi (founded 1963; Istanbul; Director general, Uǵur Cebeci)

- IKA Haber Ajansi (Economic and Commmerical News Agency; founded 1954; Ankara; Director, Ziya Tansu)

- Milha News Agency (Istanbul)

- Ulusal basin Ajansi (UBA) (Ankara; Managing editor, Oǵuz Seren).

- There are 10 Foreign Bureaus in the country with seven having representation based in Ankara, five in Istanbul, and one in Izmir. The bureaus are:

- Agence France-Presse (AFP), Ankara, Istanbul, Izmir; Correspondent Florence Biedermann

- Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata (ANSA), Italy; Ankara; Correspondent Romano Damiani

- Associated Press (AP), USA, Ankara, Istanbul; Correspondent Emel Anil

- Bulgarska Telegrafna Agentsia (BTA), Bulgaria; Ankara; Correspondent Lubomir Gabrovski

- Deutsche Presse-Agentur (dpa), Germany; Istanbul; Correspondent Bahadettin Gungor

- Informatsionnoye Telegrafnoye Agentstvo Rossii— Telegrafnoye Agentstvo Suverennykh Stran (ITAR-TASS), Russia; Ankara; Correspondent Andrei Palaria

- Reuters, Istanbul; Gen. Man. Sameeh El-Din; Internet, www.reuters.com/turkey

- United Press International (UPI), USA; Istanbul; Correspondent Ismet Imset

- Xinhua (New China) News Agency, People's Republic of China; Ankara; Correspondent Wang Qiang

- Zhongguo Xinwen She (China News Agency), People's Republic of China; Ankara; Correspondent Chang Chiliang.

Broadcast Media

Considering all of the hindrances (the common practice of suspending broadcaster's operating licenses for airing controversial material for example) and the potential physical and psychological dangers that the Turkish government provides broadcasters, an amazing variety of broadcast organizations are available. Türkiye Radyo ve Televizyon Üst Kurulu [RTÜK] (Turkish Radio and Television Supreme Council; Chair. Sedat Nuri Kayis), created in 1994, is the government agency responsible for supervision of the broadcast media in the country. It allocates channel, frequency, and band assignments; it controls the transmitting facilities of radio stations and television networks; it draws up regulations on related audiovisual concerns; and as it monitors all broadcasting, also issues warnings and assesses punishments when broadcasting laws are violated.

Until August 1983 the state possessed a monopoly on radio and television broadcasts guaranteed by Article 133 of the Constitution and also by Law No. 2954, the 1983 Radio and Television Law. In August of 1983, Parliament amended Article 133 and annulled Law No. 2954 opening the door for privately owned broadcasting to proliferate. The state still maintains its original organization founded in 1964, Turkiye Radio ve Televizyon Kurumu [TRT] (Turkish Radio and Television Corporation; Internet, www.trt.net.tr ), but is far outpaced by the number of competing options available.

TRT's radio operations consist of four national channels headed by Çetin Tezcan and the Voice of Tukey, its foreign service channel, managed by Danyal Gürdal. As of 2000, the state's television operations consist of five national channels and two satellite channels broadcasting to Europe. The general head of television operations is Nilgun Artun and directing Ankara TV is Gürkan Elçi. Other anomalies outside of the sphere of private commercial broadcasting are the radio and television services run by the United States' military forces based in Turkey and the radio operations ran by the Turkish State Meteorological Service.

Due to the proliferation of both radio and television stations the South-Eastern European Network of Associations of Private Broadcasters (SEEANPB) reports that it is can be difficult to discern which stations operate legally and which do not. Of course, steep penalties can be levied against any station found operating without a license or in violation of any government set ban. However, both the government and the media often lean on each other as supporting towers and the rule of scratching-backs can sometimes apply here; a few favors and legal infractions can "disappear." Conversely, stations that are operating illegally are by nature more difficult for the government to control—many of them originating specifically in opposition to government policies — and often have methods of thwarting government detection of their broadcasting location or causing other interference in their operations.

While most of Turkey's regulatory requirements placed on broadcasting organizations seem to be detrimental to civic life there are a few which appear more supportive. The government requires some public service obligations of private broadcasting companies. Included among these are that anti-smoking, drinking and drug-taking programs must account for at least 25 percent of total weekly airtime and be aired between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m.—children being the target audience, and that educational programs aimed at preventing traffic accidents must be offered.

Television

According to the Central Intelligence Agency, apart from the state-run TRT, Turkey has approximately 635 broadcast stations and 2,394 repeaters broadcasting to 20.9 million television sets. Also, as in other countries, satellite broadcasting continues to play an ever stronger role.

Until 1999 when its license was revoked, MED TV—a United Kingdom-based station founded in 1995—was one of the most recognized (and notorious depending on one's position) satellite channels broadcasting into Turkey. The station claimed an audience of some 35 million Kurds across Europe and the Middle East. Turkey continually lobbied for its closure and often jammed its signals. MED TV finally lost its license for what was reported to be a continued imbalance in political coverage that was deemed "likely to encourage or incite to crime or lead to disorder" by UK's Independent Television Commission (ITC).

After MED TV's demise, CTV (Cultural Television) began broadcasting, also targeting Kurdish populations and is available in Turkey. Also available in Turkey is MEDYA-TV. It broadcasts from mainland Europe, but is officially banned by the government because of its sympathies for the Kurdish separatist movement. One other channel that is available by satellite in Turkey and is of interest to the Kurdish population is Kurdistan-TV. It broadcasts from Iraq and, as opposed to MEDYA-TV, is not banned.

Radio

Beyond the TRT, there are 1044 local, 108 regional, and 36 national privately/corporately owned radio stations. Of the local stations, 229 are considered to be moderate conservative, 211 leftist, 100 extreme right wing, 92 Islamic, 45 liberal, and the remainder neutral or un-categorized. The stations reach an audience in possession of 11.3 million personal radios.

An example of the repressive policies that broadcasters have to endure can be illustrated by a statistical example concerning the RTÜK. Between April 1994 and April 2000, 184 warnings were issued to 48 radio stations. Of these, 21 radio stations experienced 6,839 days of closure. This equates to nearly 19 years worth of closure in a six-year period. TurkeyUpdate put the closure days at 4,500 levied in 2000 alone, which suggests an upward trend in sanctions.

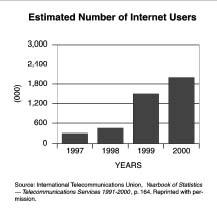

Internet

Turkey actively utilizes the Internet both in the public and the private sphere. However, government legislation and bureaucracy will likely significantly hinder the country's progress in the area.

As of 2000, there were 22 Internet service providers (ISPs) in the country and 2 million Internet users.

Summary

Amazingly, Turkey has a rather vital press that seems to be the personification of the statement, "if it doesn't kill you, it will make you stronger." Though teetering due to corporate consolidation of ownership, there is a diversity of opinion available in the country. However, whether broadly diverse or rather narrowly sectarian, press and media institutions continue to be beset by unacceptable legal regulations stifling freedom of expression. Journalists also remain subject to physical and psychological human rights abuses. Potentially, Turkey's desire to gain access to EU membership could have a positive effect across all areas and interests in the country. This seems to be the best hope for the press and the people of Turkey in the near future.

Bibliography

All the World's Newspapers . Available from .

Amnesty International. Library—Countries/Turkey . Available from http://web.amnesty.org/ai.nsf/countries/ turkey .

British Broadcast Company. Country Profiles . Available from http://news.bbc.co.uk .

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The World Factbook 2001 . Available from http://www.cia.gov .

Code of Professional Principles of the Press—Turkey .Available from http://www.uta.fi/ethicnet/turkey.html .

Columbia Encyclopedia. Turkey, Country, Asia and Europe . 6th Ed., 2001. Available from http://www. bartleby.com .

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). 2002 News Alert—Turkey: Publisher Convicted . Available from http://www.cpj.org/news .

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). Middle East and North Africa 2001: Turkey . Available from http://www.cpj.org .

Dogan, L. Media Ownership Structure in Turkey, ÇGD Progressive Journalists' Association. Available from http://www.cgd.org.tr .

EurasiaNet.org . Turkey Media Links . Available from http://www.eurasianet.org .

Free Speech TV. Available from http://www. freespeech.org .

FreedomForum.org . Available from http://www. freedomforum.org .

Freedom House. Freedom in the World . Available from http://www.freedomhouse.org .

Hellenic Resources Net. The Consitution of the Republic of Turkey . Available: http://www.hri.org .

Human Rights Watch. List of Turkish Laws Violating Free Expression. Available http://www.hrw.org .

Index on Censorship. New Law to Bar "Pessimistic' News . Available from http://www.indexonline.org .

Index on Censorship. Turkey: Military Up-in-Arms over Paris Protest . Available from http://www.index online .org .

Index on Censorship. Turkey: Publisher Escapes Jail— Chomsky Adds Tone to Troubled Debate . Available from http://www.indexonline.org .

International Federation of Journalists. IFJ Condemns Turkish Media Panic As Jobs Massacre Follows Cash Crisis . Available from http://www.ifj.org .

International Press Institute. World Press Freedom Review . Available from http://www.freemedia.at .

Jones, Dorian. "Turkish Internet Clampdown", Radio Netherlands Wereldomroep (24 May 2002) Available from http://www.oneworld.net .

Karelmas, Nilay. "Turks Get Some of the News Not All," World Press Review , Vol. 48, No. 12. (Dec. 2001) Available from http://www.worldpress.org .

Kurian, George, ed. World Press Encyclopedia . Facts on File Inc., New York: 1982.

Library of Congress. Country Studies . Available from http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs .

Maher, Joanne, ed. Regional Surveys of the World: The Middle East and North Africa 2002 , 48th ed. Europa Publications, London: 2001.

Office of the Prime Minister, Director General of Press and Information. Available from http://www.byegm.gov.tr .

Peterson, Laura. "CNN Meets the Turkish High Council," Pew International Journalism Program. Available from http://www.pewfellowships.org .

Press Wise. National Codes of Conduct: Turkey . Available from http://www.presswise.org.uk .

Redmon, Clare, ed. Willings Press Guide 2002 , Vol. 2. Waymaker Ltd.,Chesham Bucks, UK: 2002.

Reporters Sans Frontieres. Turkey Annual Report 2002 . Available from http://www.rsf.fr .

Reporters Sans Frontieres. Middle East Archives 2002 . Available from http://www.rsf.fr .

Russell, Malcom. The Middle East and South Asia 2001 , 35th ed. United Book Press Inc., Harpers Ferry, WV: 2001.

Stat-USA International Trade Library. Country Background Notes . Available from http://www.stat-usa.gov .

South-Eastern European Network of Associations of Private Broadcasters (SEEANPB). Media Legislation: Tur key . Available from http://www.seenapb.org .

The Middle East , 9th ed. Congressional Quarterly Inc., Washington, DC: 2000.

Tilic, L.D. Utaniyorum Ama Gazeteciyim (I Am Ashamed but I Am a Journalist) . Iletisim, Istanbul: 1998.

Turkey Update . Available from http://www.turkeyupdate.com .

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Available from http:// www.uis.unesco.org .

U.S. Department of State. Background Note: Turkey . Available from http://www.state.gov .

World Bank. Data and Statistics . Available from http:// www.worldbank.org .

World Desk Reference. Available from http:// www.travel.dk.

Clint B. Thomas Baldwin

Your article is very interesting for my research, but I cannot find what date it was written? If you could let me know, I would greatly appreciate it.

Yours sincerely,

Beatrice Cooke